Standing in a cool dark room with 15 or so others, I close my eyes as the scent of fresh rain wafts across my face. The sound of droplets bouncing off leaves and smacking the pavement dances around my head. If I keep my eyes shut, I can almost believe I’m in the middle of a tropical rainstorm. In a matter of seconds the sensation is gone as other noises fill the room—strange sounds with dark implications deep within memory: a crowded subway, a crackling camp fire, heavy breathing, a rushing train. With each sound a matching scent bursts forth like smoke from a smokestack, from one of two small, silver cylinders attached to a toy-boat-shaped device named the oPhone, perched on a nearby table. I’m in the Café Art/Science at Le Laboratoire Cambridge, a hybrid exhibit/café/retail space where science, culinary art, and cutting-edge design intersect in the heart of Boston’s biotech community. Next door in the cafe’s dining room, the lunch crowd inhales vaporized scotch at the bar, taking pleasure in the aroma and taste of the drink with none of the brain-altering effects of the alcohol, while the fashion-forward purchase olfactory wrap bracelets complete with interchangeable scent cartridges.

Everything about the scene is Wonka-esque, including its orchestrator. The mastermind behind the space is David Edwards, a biomedical engineer and professor of the Practice of Idea Translation at the Harvard School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, a Wyss Institute Faculty Member, and also the co-founder and CEO of Vapor Communications, which he founded with former student Rachel Fields. Edwards, who helped found Le Laboratoire first in Paris (that branch is now closed) and last year in Cambridge, MA, has quite an impressive resume. He’s penned two textbooks on applied math, invented inhalation devices for diabetics that eliminate needle delivery, designed new approaches to TB vaccination and therapy, and recently pioneered food and sensorial innovations. He has the exuberance of a child but speaks of biological complexities with authority and precision. And right now, he’s working with a team of like-minded individuals on a new media platform that should transform the way we think about our senses. The exhibit I just visited, entitled “Memory | Witness of the Unimaginable,” conceived by Dániel Péter Biró and Christophe Laudamiel, is part of Edwards’ grand quest to explore all the possibilities of scent, not only in a scientific way but in also an artistic one.

Edwards says that although there’s been a century of work to integrate scent into global communication, its diffusive nature—the fact that it mixes with other odors in the air—has made capturing the communicative power of scent difficult. “I can know that what I say, you probably hear; and what I see, you see. But I can’t really know that what I smell, you smell,” Edwards says. “And so scent transmission has mostly been used to fill space, not to communicate.” According to Edwards and his team, all of that is about to change: They aim to reintroduce the power of scent to the world by way of oClothing, oBooks, and hand-held curated scent libraries, not unlike the iPod does for music, movies, and games.

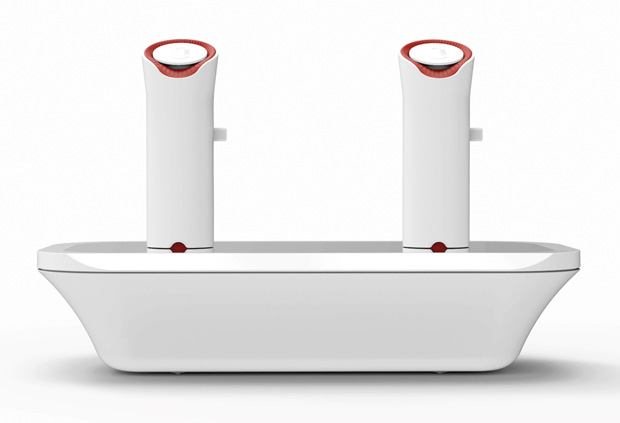

It’s an ambitious idea, its success dependent upon widespread adoption of the oPhone, the device that transmits olfactory information via scent-filled cartridges called oChips. In April, Vapor Communications introduced the oNotes app for iPad, which Edwards hopes will be the home of all your olfactory media—“the iTunes of scent,” he calls it. The same way iTunes stores your music, oNotes will be the keeper of scent-augmented songs, movies, books, and photographs.

Since the olfactory nerve is the only sensorial nerve with direct access to the brain, scent has a strong influence on emotion and memory (we process scent in the cerebellum, the same region where we process memory in the brain). This fact has many scientists like Edwards asking how this might be used to diagnose and treat diseases of memory dysfunction, such as Alzheimer’s. What can information about how we smell tell us about our health? And can we exercise our olfactory ability the way we do our bodies to promote longevity?

The Memory exhibition at Le Laboratoire just scratches the surface of some these questions while serving as an introduction to the oNotes platform. As the audio plays, quick bursts of corresponding scents are released from the oPhone, which theoretically help trigger memories in the mind. The composer, Dániel Péter Biró (a Radcliffe fellow), and Master perfumer Christophe Laudamiel, who engineered the scents for the composition, say it was intended to conjure up “historical, personal, and social memories” by pairing custom-tailored smells with a compilation of sounds—some recognizable on their own, some less so.

For Edwards, the Memory exhibit represents just one foray into an olfactory universe resplendent in possibilities. Edwards has been exploring airborne technology for more than a decade—from delivering insulin to the lungs of diabetics to developing needle-free childhood vaccines. He cofounded Medicine in Need [MEND], which develops and manufactures affordable and effective vaccines and therapies suitable for widespread use in the developing world, and holds many patents in drug delivery. But he got to this apex of blending science with art, he says, quite organically.

“Delivering drugs and vaccines through the air led me to delivering food and nutrition through the air. Then,” he says, “I began looking at delivering liquids through the air in what became known as Le Whaf. That led me to a much more poetic and aromatic arena where suddenly the delivery of taste was being accompanied by a very significant olfactory experience.” For the uninitiated, Le Whaf, developed with the help of food designer Marc Bretillot, is a dome-shaped contraption filled with piezoelectric crystals that vibrate rapidly when it’s turned on, creating ultrasonic waves. The waves create alternately low-and-high pressures through the liquid, making it bubble and then transform into a white frothy vapor cloud ready for inhalation. Think champagne without the calories.

But it’s not all fun and games. Olfactory sensations trigger emotions and memories like no other sensation we have, says Edwards. And of the three airborne sensory signals, scent is the most revelatory of human health. In fact, a 2014 study by the Harvard Aging Brain Study at Massachusetts General Hospital reports that as we age, our scent awareness declines in a manner that directly correlates with the shrinking of the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex—the temporal lobes of the brain associated with memory (1). And a similar study from researchers at Columbia University Medical Center found that olfactory impairment is presymptomatic of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. Edwards believes that designing olfactory stimulation for the monitoring of memory loss and sharpening memory may be a promising way to improve the care of dementia, including Alzheimer’s, and even Parkinson’s patients (2).

“Data that is most revelatory of health among the different sensorial data you could gather, short of drawing blood, is related to scent and taste,” says Edwards. “We’re increasingly finding that different conditions not just related to memory but also related to other kinds of disease or health-states are reflected in different abilities to smell and presumably taste. Sometimes it’s really radical where you immediately lose all sense of smell and it’s indicative of a clear condition, but probably if we had more data we would see a lot more gradual differences. There are many phenotypes that we just don’t understand because we don’t have enough data.”

The new oNotes platform, though, is gathering consumer data the same way Facebook does, which Edwards hopes will be useful in this arena going forward. “Now that we’ve digitized scent,” he says, “we’re actually gathering data about [users’] abilities and grouping this data into kind of phenotypes and then looking at genetic data and seeing whether we can’t make some sort of assessments about its means and help guide behavior in ways that are more nuanced than we can guide right now.”

Jim Buzzitta, M.D., president of Hughes Management, which oversees the construction of healthcare facilities, is very interested in the healthcare implications for Edwards’ work and was in attendance at the press screening of Memory. He wonders: How does the olfactory nerve influence mood? How does it impact health?

“Incorporating David’s new platform to help treat, to help diagnose, and even prognosticate things with regard to health is a very exciting possibility,” he says. “It’s really a wide open field because there’s been minimal amounts of experimentation and research in this area.” When we’re children, he says, our sense of smell is very acute, but as we age it becomes less so. Is this just a normal part of aging, Buzzitta wonders, or, are we failing in some way to stimulate olfaction in order to keep it strong, translating into better health and longevity? These are unanswered questions that Buzzitta hopes Edwards is on the path to answering. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if we could use it to keep people healthy rather than to wait until we have a problem and then try to treat it?”

References

- Harvard Design Magazine, “Delivering Scent, Designing Memory” by David Edwards, Volume No. 40, titled “Well, Well, Well,”, Spring/Summer 2015

- Current Geriatrics Reports, “Olfactory Dysfunction in the Elderly: Basic Circuitry and Alterations with Normal Aging and Alzheimer’s Disease” by Arjun V. Masurkar and D. P. Devanand, Volume 3, Issue 2, June 2014.)