Patents have existed throughout Europe for hundreds of years in various forms. For example, the first English patent granted to an inventor appears to have been to Giacopo Acontio in 1565 for a new type of furnace; although, in those early years, monopolies were also frequently granted by the monarch, not necessarily to inventors, but instead sometimes for the sole reason of rewarding royal favorites at public expense and/or raising taxes.

Similar systems were also in place in early continental Europe. The Republic of Venice had a decree on the protection of inventions dating from 1474; in 1594 Galileo was granted a Venetian patent for an irrigation machine. There was also a well-established system of inventors’ privileges analogous to patents granted within German states in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. However, unlike the English system, these did not prevail uninterrupted to the present day. In France, modern patent law was only enacted during the revolution in 1791 [1].

Nowadays, it is possible to seek to obtain a national patent to cover every European country by filing patent applications at the respective national patent offices, for example at the UK Intellectual Property Office (UKIPO) for the United Kingdom, and at the Deutsche Patent-und Markenamt (DPMA) for Germany. Although the different European national patent systems each have their own quirks, they share the same principles of the U.S. system: a patent application is filed at the relevant patent office, usually by enlisting the services of a suitably qualified patent attorney to prepare and file the application and then ‘negotiate’ with patent examiners at the patent office concerning the scope of protection to be granted (termed “patent prosecution”), with the aim of culminating in the grant of a patent which has the potential to be used to stop others from making or using that invention. Some might say that patent examiners, and patent attorneys for that matter, represent a rather unique species. Notably, Albert Einstein was in fact a patent examiner working at the Swiss Patent Office at the beginning of the twentieth century, who subsequently filed several of his own patent applications to cover a wide variety of inventions, even a new type of blouse (Figure 1).

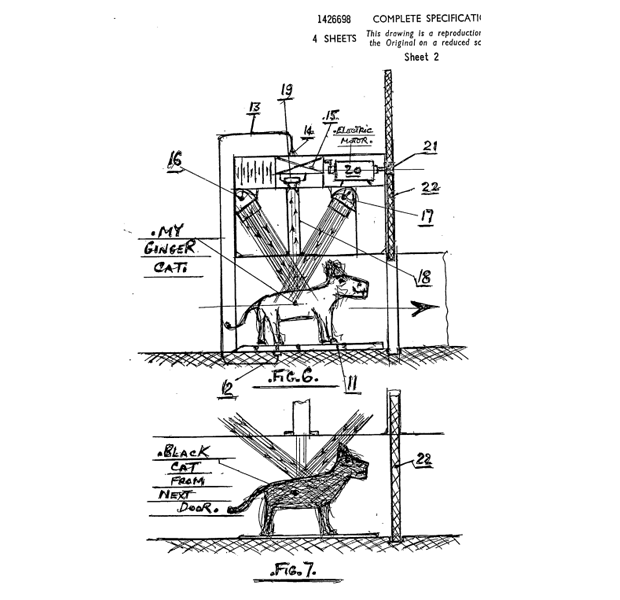

Another patent examiner, Arthur Pedrick in the United Kingdom, was also renowned for filing his own patent applications to cover some quite interesting inventions, for example see his “photon push-pull radiation detector for use in chromatically selective cat flap control and 1,000 megaton, earth-orbital, peace-keeping bomb” idea described in the UK patent application GB 1 426 698, which he filed in 1974 … and which was never granted (Figure 2).

In spite of the above, filing separate patent applications at multiple European national patent offices is of course no longer the typical route for obtaining patent protection throughout Europe.

The European Patent Convention (EPC) and European Patent Office (EPO)

Whilst the majority of European countries have long histories of their own patent systems, it was relatively recently that in 1973, and after 20 years of negotiation and debate, the first 16 European countries came together to sign the European Patent Convention (EPC), which led to the formation of the European Patent Office (EPO).

This single autonomous system for examining and granting patents has, since 1977, allowed applicants to seek to obtain a “European patent” (which is effectively a bundle of potential national patent rights) by prosecuting a single European patent application at the EPO. Once granted by the EPO, a European patent can be registered or “validated” (basically filing any relevant translations and paying any relevant fees) in the applicant’s chosen European countries from those signatory to the EPC, where it will then become equivalent to a national patent, with renewal fees payable to the national patent offices concerned. The vast majority (currently 38) of European countries are now members of the EPC/EPO, with handful of additional countries representing “extension” or “validation” states for which a European patent can be extended to cover.

Since the very first patent was granted by the EPO in January 1980, the EPO has come to represent the most common route to obtaining patent protection across multiple countries in Europe, providing the opportunity to gain patent protection covering the vast majority of the European market by prosecuting just one patent application to grant.

Despite the centralized approach to prosecuting patent applications at the EPO, after grant any litigation involving a European patent, e.g., a third party attempting to revoke a patent and/or a patentee taking action against a third party infringing a patent, must potentially be carried out in each separate national court of the countries where that patent was subsequently validated. There is, presently at least, no mechanism for centralized litigation of a patent granted by the EPO, although there is a popular centralized “opposition” procedure available to third parties at the EPO within the nine months following grant.

Despite the popularity of the EPO system, it is of course still possible to prosecute individual patent applications in one or more European countries separately to grant. Although more complicated and often less cost-effective, that strategy can result in earlier grant in certain countries (e.g., the UK), or easier grant in countries with an examination process that is less substantive than before the EPO (e.g., France).

The Future – a Unitary Patent (UP) and Unified Patent Court (UPC)?

The long awaited (having been contemplated for decades), completely centralized European patent, i.e., one which, on grant, automatically covers the majority of European countries with unitary effect and requiring a single renewal fee (the “unitary patent” or “UP”), and for which litigation in one central court (the “Unified Patent Court” or “UPC”) will be effective across all European countries was, perhaps until recently, finally looking like soon becoming a reality.

Following the UPC agreement being signed by 25 European countries in 2013, only 13 of those countries need to ratify that agreement for the UP/UPC to come into force in respect of those countries; the remaining countries subsequently joining in following their own ratifications. Since 10 countries have already ratified the agreement, in order for the UP/UPC to come into existence, only a further three ratifications are now required. Those ratifications currently must however include the UK and Germany, which represent the remaining countries of the three with the highest number of patent filings in Europe.

However, following the UK recently voting to leave the European Union (EU) (leading to the so-called “Brexit”), the future of these new systems, which, unlike for the EPC/EPO, currently require a member country to also be a member of the European Union, is consequently in doubt.

If the UK leaves the European Union and the UP/UPC is subsequently progressed without it being involved, it would not be possible to obtain a unitary patent covering the UK, but of course the mechanisms for obtaining patent protection in the UK would then remain identical to the current systems prior to the UP/UPC coming into force. As the European Patent Convention (EPC) and European Patent Office (EPO) are separate to the European Union (EU), it will remain possible to obtain a European patent, under the EPC and via the EPO, that designates the UK, and it will also remain possible to obtain national UK patents.

On leaving the European Union, expected to be no earlier than 2019, the essential requirement for the UK to ratify the UPC/UP agreement is likely to transfer to another country (most likely Italy). However, a unitary patent which no longer includes the UK will be less attractive from a commercial setting as many applicants would then have to additionally validate their European patent in the UK and pay renewal fees to the UKIPO. That is as it is now, but following the introduction of the unitary patent, those payments would be alongside the necessarily higher cost of centrally renewing a unitary patent, thereby eliminating part of the cost saving it would provide. There is also the issue of the current London-based central division of the UPC, which is actually written into the UPC agreement. Having a central division located in a non-participating country, whose legal profession will have limited rights to participate, is unlikely to be palatable to the other UPC countries. Consequently, many argue that it is in the interest of both the UK and the other members of the UP/UPC for the UK to go ahead and ratify the UPC, whilst it is still a member of the European Union, and then subsequently work out a solution to enable non-EU members such as the UK to be part of that new system.

Some Key Differences Between European and US Patents

One of the most important differences between the United States and Europe to be aware of is the lack of the one year “grace period” in European law for filing a patent application following an applicant’s own disclosure. In Europe, and indeed in many other territories worldwide, it is crucial that an applicant does not publically disclose the invention anywhere in the world before filing an initial patent application. That initial patent application could still be filed as a U.S. patent application, which can be later used as the basis for a subsequent European patent application, but unless it is filed on or before the date of the first public disclosure of the invention, the possibility of obtaining patent protection in Europe is effectively eliminated.

Another key difference is that certain subject matter is excluded from patentability in Europe, but is patentable in the United States. For example, in Europe it is possible to obtain patent protection for the medical devices and drugs which are used in methods of medical treatment, but not for the specific methods themselves. However, those methods of medical treatment might well be patentable in the U.S.

Other differences exist in the ability to challenge/litigate granted patents. The EPO provides a nine-month period after the publication of grant for a third party to oppose the patent, which is then reassessed by the Opposition Division of the EPO. This procedure, which has the potential to knock out a newly granted European patent centrally, is, to an extent, analogous to the recently introduced “post grant review” procedure offered by the USPTO. However, whilst it is also possible to eliminate a U.S. patent centrally by challenging it in a federal court, e.g., during infringement proceedings, it is currently not possible to centrally revoke a European patent through a single court. That must instead be done through the individual national courts of the countries in which the European patent has been validated. Of course, the possible introduction of the UP/UPC (see above) might however soon provide an opportunity for that to happen in Europe, at least for those territories which are part of the UP/UPC.

Conclusion

Whilst obtaining a patent in Europe shares many of the same fundamental principles of the same process in the United States, key differences exist which need to be borne in mind from a very early stage. Furthermore, there is the necessity to consider how many of the multiple different countries making up the European market one might wish to obtain patent protection in. This process may sooner or later be made simpler by the introduction of the UP/UPC, but on that front we will have to wait and see for now.

References

- Philip W. Grubb, Patents for Chemicals, Pharmaceuticals and Biotechnology, 4th Edition, Oxford University Press, 2004.