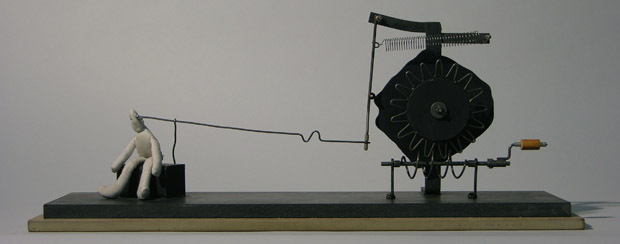

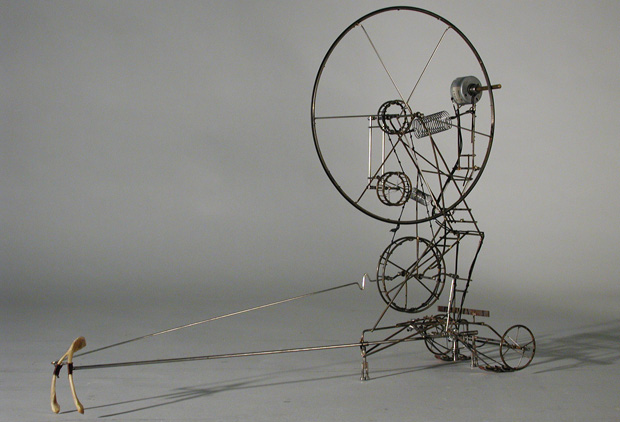

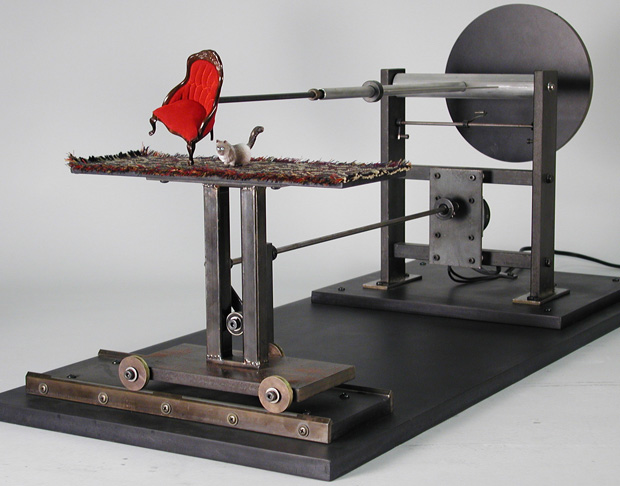

Artist Arthur Ganson describes his kinetic sculptures as a cross between mechanical engineering and choreography. And if you’ve had a chance to see one of his works, you’ll understand why. Delicate assemblages of interconnecting gears, springs, cams, ratchets and sprockets fashioned out of spot-welded baling wire perform whimsical acts with mostly found objects. An elaborate machine allows a chicken’s wishbone to walk a thin roadway (Machine with Chicken Wishbone, 1988). Another anoints itself with lubricating oil scooped up from a pan (Machine with Oil, 1990). Yet another performs a ballet dance with a chair (Machine with Chair, 1995) while another, a push cart, allows small metal mesh tubes to writhe and contract, just like worms, on a tray filled with spiraling blue fluff (Inchworms, 1996). From a distance his sculptures, which are sometimes hand-cranked and sometimes motorized, have a homespun 19th century quality. They could be absurdist wire doodles. Closer up, the movement and gesture implicit in his work becomes strangely hypnotic — often humorous, childlike, introspective, and existential. Ganson admits that he has been strongly influenced by the likes of such Dadaists as Marcel Duchamp and Jean Tinguely.

Ganson, who lives near Boston, has no formal engineering background. Rather, he received a bachelor’s of fine arts degree from the University of New Hampshire and later followed that up as an artist in residence in the Mechanical Engineering department at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1995–1999. His sculptures have been exhibited at a number of science museums and art galleries and are part of the ongoing exhibit “Gestural Engineering” at the MIT Museum. We caught up with Ganson recently for a conversation about his work.

PULSE: What drives you to do the type of work you do?

Ganson: It’s difficult to say what fundamentally drives me to do what I do, but the work is a natural assimilation of my disparate interests and natural capabilities. As a young child I was always interested in the way things moved and I expressed this initially by drawing animations on the edges of paperback books. I was also very introverted and shy and had an occasional stutter, so I began expressing myself with what I could construct with my hands, as opposed to what I would say with words. In my senior year of high school I became very involved with computer programming, and this got me thinking about systems and logical flow. In college, when I began to make the first pieces, they took the form of very fragile wire machines — delicate constructions which required extremely careful and focused hand-work. They were complex spatial constructions that somehow embodied my thoughts and feelings. I can also say that I’m just passionate about inventing things and am always thinking about relationships and am always being inspired by seeing things that trigger ideas. This is the natural state of things for me.

PULSE: From what I understand, you have no formal engineering degree. Where did your love of engineering come from? Where did you develop the skills needed to create your elaborate works?

Ganson: I began to build my engineering intuitions when I started to make sculptures that moved. For me, engineering is like color theory for a painter or harmony for a composer. There is no separation at all for me between the engineering and aesthetic issues. My capacities as an engineer have developed slowly and through the experience of actually making things. I often say my knowledge of engineering has been honed by 30 years of ‘making mistakes,’ but I firmly believe that each time I have imagined something and gotten a different result, I’ve learned something in the process.

PULSE: Many artists might feel that there is a dichotomy between the arts and more technical or scientific fields, such as engineering. Did you ever feel this? Are the arts and sciences part of the same coin? What can artists teach engineers, and what can engineers teach artists? Can a biomedical engineer working on a medical device have her work informed by art, and how?

Ganson: This question is often asked and here is my take on it: All fields share aspects of each other and there are no clear delineations. Everything is a matter of perspective. While informed by all that has come before, the original work of both the scientist and artist is primarily fueled by their imaginations. The engineer and the painter each rely upon technology and each invents with materials and concepts that are pertinent to their fields. Material properties are fundamental to both the engineer and the artist, but without pure imagination nothing would exist. So, for me a biomedical engineer is a kind of artist and the question is a false one. Everything in the life of the biomedical engineer plays a role in her work- just as every other artist.

PULSE: Although you work with machines, your work seems really about humanity and in particular, the human gesture. Is that a fair characterization? How did you arrive at the idea of using machines and machinery to replicate such human acts — the ballet dance with the chair, the writing on a tablet, the opening of a fan?

Ganson: Yes, this is a fair characterization. I’ve talked about gesture earlier and talked about the evolution of my thinking and impulse to make art. To answer the question directly then, I arrived at this place with NO THOUGHT ABOUT WHERE I SHOULD GO… I was just doing what came naturally and this is where I ended up. It was an unconscious evolution.

PULSE: Much of your work in the MIT exhibit was done in the 90s. What are you working on these days? Has your work changed at all? Do you have new problems or concerns?

Ganson: The last piece I made was a small wire construction inspired by seeing an exhibition of Picasso. I’ll always be working in wire as it was the fundamental material for me. On the other hand, I’m thinking much about making very large machines of welded steel- perhaps 20 or 30 feet tall. I’m thinking that they would share many of the same qualities as the small delicate wire pieces but would be monumental in size. At the same time I’m about to jump in and learn SolidWorks as that will open up a whole world of new designing and building possibilities. I have many inventions in mind as well as sculpture that might be most efficiently realized by new processes. The first piece will be another version of ‘Cory’s Yellow Chair.’ I’m very excited about jumping into this project! The work is always evolving and each day there are new ideas. I never know where it will take me but it’s an interesting ride!