It is said that time marches on, and one thing is certain: Hearing loss marches right along with it. The recorded history of hearing loss goes back hundreds of years, and attempts to correct hearing loss have been in existence since the very first person to cup a hand behind one ear. The good news is hearing aids and other assistive listening devices have come a long way since the first rudimentary attempts at improving hearing. Yes, hearing aid technology is still evolving and is still far from perfect. Well, nothing is perfect in life, as perfection is always an unreachable limit.

13th century to 19th century: From animal horns to ear trumpets

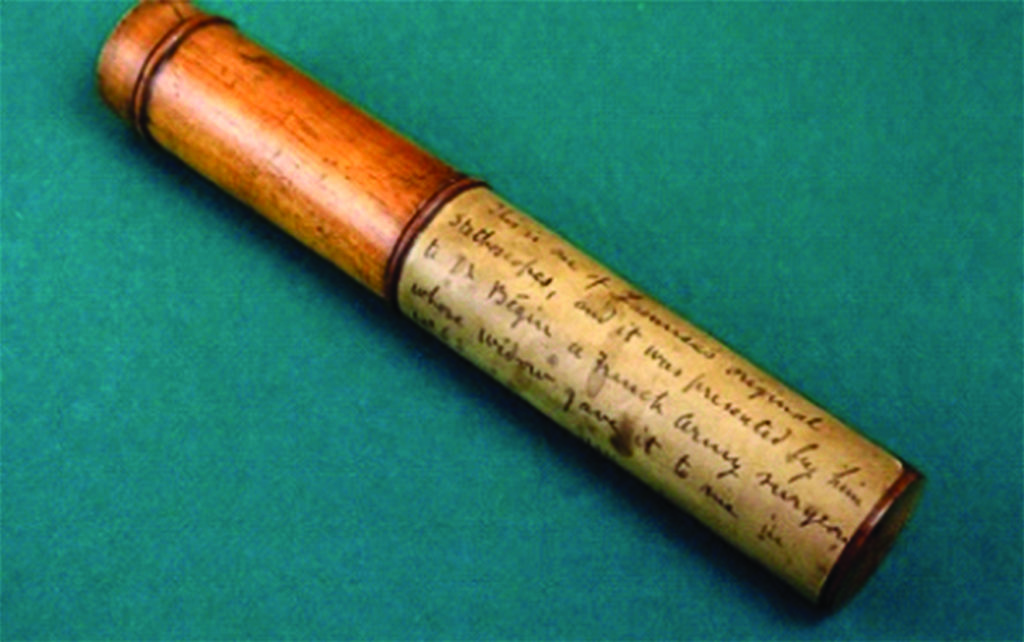

As early as the 13th century, those with hearing loss were using hollowed out horns of animals such as cows and rams as primitive hearing devices. It was not until the 18th century that the better ear trumpet was invented. Funnel-shaped in design, ear trumpets were man’s first attempt at inventing a device for treating hearing loss. They did not amplify sound, however, but worked by collecting sound and funneling it through a narrow tube into the ear. Bulky, these ear trumpets and the subsequent speaking tubes did not work all that well. A cousin device was the stethoscope, invented in France in 1816 by René Laennec at the Necker Enfants Malades Hospital in Paris. It consisted of a wooden tube and was monaural. Laennec invented the stethoscope because he was no comfortable placing his ear directly onto a woman’s chest to listen to her heart. Not only that, but it was a clever simple way for improving audition of the various chest noises during respiration (Figure 1).

Apparently, Laennec’s idea first came from rolling in a newspaper as a cylinder and using it as a hearing tube. Really a eureka kind of mental flash. However, improving audition of the deaf or quasi-deaf guy or just to compensate for the normal age loss of hearing capacity was the only option until electricity and the telephone were invented in the 19th century. The use of ear trumpets for the partially deaf dates back to the 17th century. The earliest description of an ear trumpet was given by the French Jesuit priest and mathematician Jean Leurechon2 in his work Recreations Mathématiques (1634). Polymath Athanasius Kircher3 also described a similar device in 1650. By the late 18th century, their use was becoming increasingly common. Collapsible conical ear trumpets were made by instrument makers for specific clients. A well-known model of the period was the Townsend Trumpet, made by the deaf educator John Townsend.4 The first firm to begin commercial production of the ear trumpet was established in London in 1800. In addition to ear trumpets, there were hearing fans and speaking tubes. These instruments helped amplify sounds,

while still being portable. However, these devices were generally bulky and had to be physically supported from below. Later, smaller, hand held ear trumpets and cones were used as hearing aids. A special acoustic chair was designed for the ailing king of Portugal in 1819. The throne had ornately carved arms that looked like the open mouths of lions. These holes acted as the receiving area for the acoustics, which were transmitted to the back of the throne via a speaking tube, and into the king’s ear. Finally, in the late 1800s, the acoustic horn, which was a tube that had two ends and a cone that captured sound, was eventually made to fit in the ear.

Johann Nepomuk Mälzel5 began manufacturing ear trumpets in the 1810s (Figure 2). He notably produced ear trumpets for Ludwig van Beethoven, who was starting to go deaf at the time. These are now kept in the Beethoven Museum in Bonn. Maelzel died on a ship in the harbor of La Guaira, Venezuela, reportedly from alcohol poisoning.

Toward the late 19th century, hidden hearing aids became increasingly popular. Rein7 pioneered many notable designs, including his “acoustic headbands,” where the hearing aid device was artfully concealed within the hair or headgear. Reins’ Aurolese Phones were headbands, made in a variety of shapes, that incorporated sound collectors near the ear that would amplify the acoustics. Hearing aids were also hidden in couches, clothing, and accessories. This drive toward ever-increasing invisibility was often more about hiding the individual’s disability from the public than about helping the individual cope with his problem. F. C. Rein and Son of London ended its ear trumpet manufacturing activity in 1963, as both the first and last company of its kind. There was another unexpected application: the Pinard horn (see footnote 7), a type of stethoscope used by midwives designed similarly to an ear trumpet. It was a wooden cone about 8 inches long. The midwife would press the wide end of the horn against the pregnant woman’s belly to monitor heart tones. Pinard horns were invented in France in the 19th century and are still in use in many places worldwide (Figure 3).

19th century to 20th century: The first electronic hearing aids

The invention of the telephone combined with the practical application of electricity in the 19th century had a tremendous impact effect on the development of hearing aids and other assistive hearing devices. People with hearing loss quickly realized they could hear a conversation better through the telephone receiver held up to their ear than they could in person. However, Thomas Edison, who experienced hearing loss firsthand, saw room for improvement. In 1870, he invented a carbon transmitter for the telephone that amplified the electrical signal and increased the decibel level by about 15 dB. Although an amplification of about 30 dB is usually necessary to allow those with hearing loss to hear better, the invention of the carbon transmitter for the telephone paved the way for the technology that would eventually be used for carbon hearing aids. Although not ideal due to their limited frequency range and tendency to produce scratchy sound, carbon hearing aids were in use from 1902 until the advent of the next wave of technology: the vacuum tube.

1921–1952: Vacuum tube technology

Beginning in the 1920s, hearing aids using vacuum tubes were able to increase the sound level by as much as 70 dB. These sound levels were achieved because vacuum tubes controlled the flow of electricity better than carbon. The problem was the size. In the beginning, the devices were very large, about the size of a filing cabinet, so they were not portable. By 1924, the size of vacuum tube hearing aids had been reduced so all of the components could fit in a small wooden box, with a receiver that the user held up to the ear. Despite the improvement, they were still heavy, bulky, and conspicuous and amplified all sound, not just the sounds the user wanted to hear. Improvements in technology continued in 1938 when the first truly wearable hearing aid was introduced. It was an earpiece, wire,

and receiver that could be clipped to the user’s clothing. Unfortunately, this model also required the use of a battery pack that was strapped to the user’s leg. Thanks to technology developed during World War II, the late 1940s finally saw the production of hearing aids with circuit boards and button-sized batteries, allowing the batteries, amplifier, and microphone to be combined into one portable, pocket-sized unit. Even though they were marketed as discreet, the pocket unit connected to individual earpieces with wires that made them less than appealing from a cosmetic standpoint. Despite the advances, the world still waited for small, one-piece hearing aids that could fit entirely in the ear and truly be worn discreetly. Fortunately, they did not have to wait long.

Mid-20th century: The transistor

The move to smaller, more discreet hearing aids finally got underway in 1948, when Bell Telephone Laboratories invented the transistor. Transistors can start and stop the flow of a current and also control the volume of a current, making it possible to have multiple settings in one device. Norman Krim, an engineer at Raytheon and the inventor of the previous subminiature vacuum tube technology, saw the potential application for transistors in hearing aids. By 1952, Krim was able to create junction transistors for hearing aid companies. The transistor not only enabled hearing aids to be made smaller; they could finally be worn either completely inside or behind the ear. The new hearing aids were so popular and successful that more than 200,000 transistor hearing aids were sold in 1953 alone, eclipsing the sale of vacuum tube models. Capitalizing on the new technology, one of the first hearing aids to be worn almost entirely in the ear was invented in the late 1950s by Otarion Electronics. Called the Otarion Listener,10 the electronics were embedded in the temple pieces of eyeglasses. These hearing glasses caught on and several versions were soon introduced by other companies.

Late 20th century: Analog to digital

By 2005, digital hearing aids represented 80% of its market. Eventually, hearing aid manufacturers developed the ability to make the transistors out of silicon, enabling hearing aids to shrink even further. Hearing aid technology closer to that which we know today was introduced in the 1960s; in these versions, the microphone went in the ear and was connected by a small wire to an amplifier and battery unit that was clipped to the ear. This technology stayed largely the

same until the 1980s, upon the introduction of digital signal processing chips. The first to use the technology created hybrid digital–analog models until 1996, when the first fully digital hearing aid model appeared.

21st century: High tech and new horizons

By the year 2000, hearing aids had the ability to be programmed, allowing for user customization, flexibility, and fine tuning, and by 2005 digital hearing aids represented about 80% of its market. Digital technology is the same circuitry that is used in cell phones and computers. Today’s hearing aids can be fine-tuned by a hearing care professional and customized to an individual’s hearing needs. They can adapt to different listening environments and be connected to other high-tech devices such as computers, televisions, and telephones. Special features allow compatibility with other electronic devices and accessibility in public spaces. Yes, we have come a long way from the days of ear trumpets, and hearing aids continue to evolve as technology advances. On the market today are products with a truly rechargeable hearing aid battery. Many hearing aids are smart enough for adapting to different listening situations without the intervention of the user. Long-wearing hearing aids, which can stay in

the wearer’s ear canals for several weeks, have been available for several years. Certainly in the future, hearing aids will continue to increase in performance and comfort while decreasing in size.

This article is only a quick overview of the subject which started as extremely rudimentary ways of improvement. Beethoven’s deafness dramatically, perhaps we should say tragically, influenced his musical life and never was a clear explanation reached by the limited medical knowledge of those days. He was born on December 17, 1770, and passed away on March 26, 1827, at age 56, still young, indeed. The trumpets he used are now kept in the Beethoven Museum in Bonn, Germany.12 Technology has been and still is how to proceed so that a better happier life to a human being is obtained. Thus, many productive men and women could continue their respective activities. The hope continues that these new technologies will be available to all irrespective of wealth or social status.

Max E. Valentinuzzi (maxvalentinuzzi@arnet. com.ar) is a professor emeritus with the Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina, and investigator emeritus with Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas, Argentina. He is a Life Fellow of the IEEE.