Dentists and health care providers look for ways to expand access to underserved populations

About a decade ago, Dian Baker, a professor at Sacramento State School of Nursing, responded to a directive from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) asking health care practitioners to do something about the thorny and serious problem of ventilator hospital-acquired pneumonia, which afflicts thousands of people each year. After consulting with colleagues on the issue, Baker noticed something interesting. Although hospital ventilators had been widely assumed to be the cause of this problem, the truth was that most people getting pneumonia in hospitals weren’t on ventilators. The true culprit may come as a surprise: Nurses were shirking the unpleasant task of brushing the teeth of seriously ill patients.

“Nurses, who are responsible for patients’ oral care, were reporting that they didn’t want to do it because it meant picking toothbrush bristles out of patients’ mouths,” said Baker in a 2020 interview. “Many nurses don’t even know that germs in the mouth are related to pneumonia, and that hospital-acquired pneumonia can be prevented.”

It was a discovery that elegantly underscores the critical nature of tending to one’s teeth. Neglected teeth and gums contribute to health problems ranging from cardiovascular disease to pneumonia to pregnancy complications. When people don’t get routine dental care, they risk not only acute issues like losing a tooth, but chronic health issues that may beleaguer them for the rest of their lives. Unfortunately, many in the United States aren’t tending to their teeth. In 2014, more than one in five people (and one in ten kids) had not visited a dentist in several years, according to the Health Policy Institute at the American Dental Association. Between 2013 and 2016, nearly a third of adults between the ages of 20 and 44 (and 17% of children) were walking around with untreated cavities, according to the CDC.

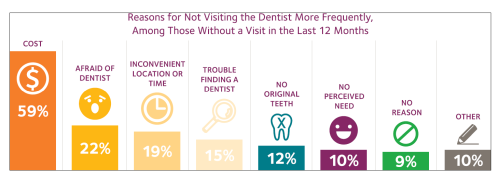

People are avoiding dentists because of the cost (59%), an inability to find a convenient dentist or appointment time (19%)—and then there’s just the general fear of the dentist (22%)—according to the ADA survey (Figure 1). To make matters worse, about 74 million Americans had no dental coverage in 2016, according to the National Association of Dental Plans. Aware of these kinds of statistics, public health advocates and dental providers are looking for ways to entice more people into dental chairs, despite the costs and regardless of where patients may happen to live. (Fear of the dentist may be a harder problem to solve.)

As health care providers and policymakers grapple with broadening access, three nascent trends have taken root which hold promise of getting more people to the dentist.

Integrating oral health and primary care

One way of ensuring that more people see a dentist is ensuring that people are given the opportunity, even when it may not be uppermost in their minds. Programs around the country are seeking to integrate primary care with dental care so that a person, let’s say going in for an annual physical, also gets an oral health evaluation and is referred to a dentist who might be located right across the hall.

In Oregon and Southwest Washington, Permanente Dental Associates, a professional corporation owned and managed by dentists, works with the Kaiser Foundation Health Plan to operate the Kaiser Permanente Dental Program which seeks to do many of these things. In this model, overall health and dental care are seamlessly melded together. When patients see dental practitioners, they, with the assistance of a licensed practical nurse, also address medical care gaps. They might also set up screenings and routine blood work. When patients visit their doctor, on the other hand, that doctor also keeps oral health in mind. Pediatricians periodically apply fluoride varnish to the teeth of young patients and physicians refer diabetic patients to a dentist if they have not seen one recently. Through shared electronic health records, any notes generated by a primary care visit are also accessible to the dentist. When a dental patient is treated, a primary care physician is aware of what happened and why.

“The goal is to shift dental services away from treating the effects of disease and toward prevention, monitoring and reversal of disease,” says John Snyder, executive dental director and CEO of Permanente Dental Associates (Figure 2).

Snyder says that a trip to the dentist can be an important touch point in the health care system to ask about routine medical care. “The dental team is part of the patients’ health care team so it’s part of our job to encourage patients to close medical care gaps, schedule preventive care, or to visit adjacent or nearby Kaiser medical facilities,” says Snyder.

In a similar initiative, James Crall, professor and chair of the Division of Public Health and Community Dentistry at UCLA (Figure 3), has helped create the UCLA–First 5 LA Oral Health Program, which is particularly focused on eliminating barriers that limit access to oral health care for young children while increasing the capacity of community clinics to serve as patient-centered “dental homes.” Dental clinics have been set up inside 22 community health centers, making it easier to have an exchange between physicians and dentists.

Primary doctors are trained to make oral health and caries-risk assessments and apply fluoride varnish; quality improvement methods are used to integrate medical-dental service delivery and electronic medical and dental records; and there is the all-important proximity between the doctors’ and dentists’ clinics so that patients care can be coordinated at the same facility. A particularly important goal, says Crall, is to get children under age 3 to the dentist, when many people assume it’s unnecessary but when it is actually critical to preventing problems that may plague a child for years to come. “The best predictor of tooth decay in permanent teeth is tooth decay in primary teeth,” says Crall. “So, if you ignore that signal and just let those teeth fall out, guess what? Now you get some nice new teeth and they get cavities, too, and you just totally ignored them and blew five years of opportunity to get that kid help.”

“We are realizing more and more that providing dental care during a primary care visit can have tremendous impact on a child’s overall health,” says Francisco Ramos-Gomez, director of the UCLA Center for Children’s Oral Health. “Children are far more likely to see a primary care provider by age one than a dental provider.” At UCLA’s CARE PD project and Infant Oral Care Program (IOCP), pediatric medical residents and pediatric nurse practitioners train alongside pediatric dental residents to provide dental exams, apply fluoride varnish and provide anticipatory guidance and counseling. Ramos-Gomez says this model will soon be expanded to include training for family medical residents and family nurse practitioners.

Other initiatives include the Medical Oral Expanded Care Initiative (MORE Care) which has expanded dentistry into rural health centers in South Carolina, Pennsylvania, Colorado, and Oregon. Many of these programs gained momentum after a 2014 report of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services that called for a new framework for integrating oral health and primary care. Among other things, it suggested training more physicians in oral health, developing infrastructure that would allow doctors’ offices to also treat patients for dental issues, and modifying payment policies to make it easier for providers to get reimbursed for oral health services. In recent years, community centers from New Hampshire to Rhode Island have jumped onboard.

These changes, says Crall, recognize how important good dental care is not only to the overall health of people, but to the sustainability of our larger health system, because, he says, in the end, “you can’t drill your way out of this problem.”

Teledentistry to the rescue

What does a trip to the dentist look like if the dentist is in one place and the patient in another?

Nathan Suter’s practice in House Springs, MO (which he wrote about in the July 2020 issue of Dental Economics), provides a window. Suter has been using teledentistry since 2015 in what he calls an “asynchronous store-and-forward” approach.

“I have patients booking video chat appointments with our office, and they fill out a detailed digital form prior to their visits,” Suter says. “It is this form that determines emergent/urgent care as well as the patient’s COVID-19 risk level. In many cases, I can directly message patients and give them guidance without even having to hold that scheduled video chat.”

There is nothing like a pandemic to drive disruptive innovation. Although prior to COVID, Suter says he “tried for years with no success to bring this tool to the attention of many leaders in the dental industry,” it wasn’t until after COVID that he saw some success. In a short time, legal and regulatory hurdles got cleared away. A tracking poll from the ADA Health Policy Institute published in April 2020 confirmed that more than 25% of dentists now offer some form of virtual evaluation. Sometimes this entails a video chat with a patient who is at home. Other times, a hygienist collects diagnostic data like radiographs, periodontal charting, digital scans, and tooth impressions, before sending it over to a dentist at another location. Thanks to this model, dentists are seeing more patients safely during the pandemic, while conserving precious personal protective equipment. Patients, without access to transportation, who live in rural areas, or who may be at high-risk for developing a severe case of COVID-19, are finding it more convenient, too.

Suter says he has conducted 100% of his hygiene checkups remotely since June 2020. He has also created a consulting company, Access Teledentistry, for dentists interested in the concept and cofounded a care coordination platform called Healier helping dentists coordinate telehealth and in-person visits (Figure 4). A major game-changer, he says, has been a 3D intraoral scanner (the iTero Element 5D) allowing users to record color images inside a patient’s mouth while making comparisons over time using time-lapse technology.

Marc Ackerman, executive director of the American Teledentistry Association, believes that the majority of dental practices are now using some form of teledentistry. “The COVID-19 pandemic has propelled the acceptance and use of telehealth years ahead of where it otherwise might be,” he says. Ackerman notes that the American Dental Association has amended its guidelines to embrace telehealth and advocate that insurance providers cover remote treatment in the same way they do in-person treatment.

Although COVID has made teledentistry more palatable to mainstream dentists, those in public health have used it successfully for many years. In 2015, Capitol Dental in Oregon, for example, initiated a pilot program to bring “virtual dental homes” to children in rural Polk County, which has a high percentage of low-income migrant families. Dental hygienists and assistants sent into schools have shared radiographs and photographs of patients with a remote dentist through a secure server. From there, a dentist develops a treatment plan. Many of these children would have had no access to a dentist, otherwise.

“This technology has even more potential in the future as new communication tools are integrated into existing practice management solutions and artificial intelligence diagnostic tools are added to the workflow,” says Suter, who himself has used teledentistry to screen children in schools and residents in nursing homes.

In the future, connected smart devices will make teledentistry even easier, by allowing for the constant monitoring of a patient’s dental health, says Suter. “This has some great potential in an uncertain future where regular maintenance and elective treatment may not be sought out by patients.”

The rise of dental therapists

What happens when a trip to the dentist really means a trip to the dental therapist?

At Apple Tree Dental in Minnesota, a trip to the dentist often means seeing a dental therapist—a licensed mid-level dental care provider with less training than a dentist—who can do many of the basic routine procedures a dentist might. (Think of a nurse practitioner relative to a doctor.) Dental therapists conduct routine examinations, take x-rays, drill and fill cavities, apply sealants, and extract first teeth. A big part of the job revolves around patient education.

“My day in clinic mainly consists of restorative dentistry,” says Heather Luebben, who has been a dental therapist at Apple Tree since 2008 (Figure 5). Luebben handles some emergency procedures and refers cases to a dentist when they fall outside her scope of practice. She sometimes uses teledentistry to conduct hygiene exams for low-risk patients. These are done both asynchronously and synchronously. Her patients include those with special needs, the elderly, and those with low-income.

“We really are here to provide care and open up access to underserved populations,” she says. “While we cannot provide any direct services dentists cannot also provide, we are educated and trained to work with specific populations, and we are also dual-licensed as dental hygienists meaning we often provide restorative and preventive services in one appointment for patients. This can reduce the number of visits which can be important for those traveling far distances, those with difficulties leaving work, and those who require interpreters, medical transportation, staff to accompany them, etc.”

While Minnesota became the first state to license dental therapists in 2009, Alaska has used Dental Health Aide Therapists (DHATs) since 2005 to provide dental care for Alaska Natives living in remote villages. (DHATs receive a two-year, post-high school primary care training.) A 2018 study linked DHATs to improved dental outcomes such as fewer extractions among children and adults in Alaska’s Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta.

Dental therapists have been used around the world since the 1920s and now work in more than 50 countries. In the U.S., Minnesota, Maine, Arizona, Michigan, and Vermont have all passed legislation authorizing dental therapists to practice and at least eight other states—among them Florida, New York, and Wisconsin—are considering legislation allowing dental therapists to practice, according to data from the American Dental Hygienists’ Association.

“Let me say this, it’s catching on,” says Jean Moore, director of the Center for Health Workforce Studies at the University at Albany, State University of New York. Moore and her colleagues have studied the contributions of dental therapists at Apple Tree Dental in Minnesota and found that while dental therapists provide access to dental care, “where it simply didn’t exist before,” they also have the unexpected consequence of boosting the income of many dentists, many of whom were initially resistant to the idea of dental therapists for fear they would lose income. Instead, what happened is that dental therapists, focusing on basic dental care, freed up dentists to concentrate on more complicated, high-cost procedures.

“I think it has a lot of promise,” says Moore, who estimates that about 150 dental therapists are currently practicing around the country. “As we do more research, it shows the value of having someone like a dental therapist on the oral health team. When I look at how many states are contemplating recognizing dental therapy, I’m amazed.”

For More Information on Dental Care Models

- L. Keough, M. Clifford, M. Langelier, N. Goodwin, and T. Melnik, Compendium of Innovations in Oral Health Service Delivery. Rensselaer, NY, USA: Oral Health Workforce Research Center, Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, SUNY Albany, Feb. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Compendium_of_Innovations_in_Oral_Health_Service_Delivery_2020.pdf

- M. Langelier, S. Surdu, and J. Moore, The Contributions of Dental Therapists and Advanced Dental Therapists in the Dental Centers of Apple Tree Dental in Minnesota. Rensselaer, NY, USA: Center for Health Workforce Studies, School of Public Health, SUNY Albany, Aug. 2020. [Online]. Available: https://www.chwsny.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/CHWS_Contributions_of_DTs_ADTs_at_Apple_Tree_Dental_2020.pdf