Imagine if you didn’t have to fill out paper forms each time you visited a new doctor or if you could access your personal medical records from your home computer. In a world where we can pay bills on our cell phones and send rovers to explore Mars, these scenarios don’t seem that far-fetched. But for many patients and doctors in the United States, current electronic health records (or EHRs) are far from ideal. The same is true for most of our pets (and even for agricultural animals)—pick one of these animals and, in all likelihood, its medical records are similarly siloed. But oddly enough, if you were a tree kangaroo, you might have better luck.

EHR Use is Growing, but Satisfaction is Declining

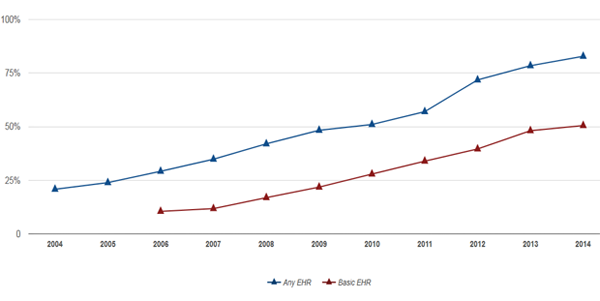

The number of clinics and hospitals using EHRs has skyrocketed over the past few years thanks to the Health Information Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act (HITECH Act). The HITECH Act provided financial incentives for Medicare and Medicaid providers to adopt EHRs starting in 2011 and decreased Medicare reimbursement rates for those who didn’t adopt EHRs starting in 2015. As of 2014, around 8 out of 10 office-based physicians were using them—a number that’s likely to be even higher now [1] (Figure 1, below).

[accordion title=”Figure 1. EHR adoption has nearly doubled since 2008″]

Office-based Physician Electronic Health Record Adoption: 2004-2014

As of 2014, a majority of office-based physicians have adopted electronic health records (EHRs). By the end of 2014, about 8 in 10 (83%) of office-based physicians had adopted any EHR [2] and about half (51%) adopted a “Basic EHR” [1]. Since 2008, office-based physician adoption of any EHRs has nearly doubled, from 42% to 83%, while adoption of Basic EHRs has nearly tripled from 17% to 51%. Between 2013 and 2014, adoption of any EHR grew by 6% and Basic EHR adoption grew by 5%.

Notes:

- Physicians adopted a Basic EHR if they reported their practice performed all of the following computerized functions: patient demographics, patient problem lists, electronic lists of medications taken by patients, clinician notes, orders for medications, viewing laboratory results, and viewing imaging results. The core capabilities of a Basic EHR were defined by DesRoches, et al. in the 2008 manuscript.

- Any EHR system is a medical or health record system that is either all or partially electronic, and excludes systems solely for billing.

- Data include non-federal, office-based physicians, and exclude radiologists, anesthesiologists, and pathologists.

Figure and caption credit: Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ‘Office-based Physician Electronic Health Record Adoption: 2004-2014,’ Health IT Quick-Stat #50. September 2015.

[/accordion]

While more doctors are using EHRs now, rates of satisfaction with these systems are actually decreasing. A 2015 survey by the American Medical Association and American EHR Partners found that only 22 percent of physicians were satisfied with their EHR system—down from 39 percent in the same survey five years prior—and “43 percent said they had yet to overcome the productivity challenges related to their EHR system.” [2]

Amazingly, a US$30 billion government stimulus spent on systems to improve healthcare quality and efficiency has resulted in technology that actually makes a physician’s job harder —to such an extent that it is impacting physician job satisfaction. Christine Sinsky, MD, VP of Professional Satisfaction for the American Medical Association spoke about this issue at an IEEE Pulse on Stage symposium in Las Vegas in 2016 (Figure 2, right). She said that EHRs were the major driver of physician career dissatisfaction, leading to a dismal situation where “over half of US physicians are currently experiencing signs of burnout, and the rates of burnout are increasing dramatically.”

Why are EHRs taking such a toll on physicians? Sinsky cites three reasons: 1) EHRs take too much time; 2) EHRs decrease the amount of face-to-face time doctors have with their patients; 3) EHRs degrade the quality of clinical documentation. Adding fuel to the fire is the fact the EHRs in their current incarnation have limited functionality.

An example of this limited functionality is a lack of so-called “interoperability” between different EHR systems, such as those created by the healthcare IT giants Epic and Cerner (see “Seeking Solutions: A Roadmap for Interoperability” below). According to the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), “only 14 percent of ambulatory providers shared electronic health information with providers outside of their organization” in 2013 [3]. This means that, even though doctors are spending a ton of time inputting data and notes in their EHRs, their clinics often end up printing these records and faxing or mailing them to other offices and hospitals.

Electronic Veterinary Health Records are All Over the Map

“Veterinary EHRs have no financial support or governmental mandate, so quality and use is all over the spectrum,” says Sonnya Dennis, DVM, DABVP. Dennis is a veterinarian in private practice as well as the President of the Association for Veterinary Informatics. “Veterinary EHRs can be good or horrible,” says Dennis. “It depends on the software, company support, and the doctor implementing it. Some docs confuse ‘easy to use’ with ‘good quality.’”

A recent survey of small animal veterinary medical practices in Massachusetts led by Joann Lindenmayer, DVM of Turfs University found that around 80 percent of practices used some version of EVHRs—63 percent were using a mix of both electronic and paper-based records and 17 percent had switched completely to EVHRs [4].

As in human medicine, there are mixed opinions on the use of EVHRs in veterinary medicine. Lindenmayer’s study found that while 71 percent of veterinarians in completely electronic clinics reported being satisfied, only about 34 percent of veterinarians in clinics that used a combination of electronic and paper records reported satisfaction with their systems—suggesting that these practices have held onto their paper system because their EVHR systems weren’t meeting their needs.

However, EVHRs—like human EHRs—do have the potential to change healthcare for the better. And for many veterinarians, EVHRs help their practices run more smoothly. “I’m totally paperless. I do everything with my software… it makes it a lot easier to keep track of things,” says Wayde Shipman, DVM, a veterinarian in private practice, Veterinary Medical Information Specialist at Virginia Tech and president of Veterinary Medical Databases (Figure 3, right). “I don’t lose records. You can actually read records because of simple things like my handwriting is so illegible.”

But problems with interoperability—the boogeyman of the human EHR world—also prevent EVHRs from living up to their potential. While large corporate practices like Banfield Pet Hospitals and VCA Hospitals have their own proprietary EHR systems that allow for easy record sharing between hospitals within the same network, most private clinics act as individual silos—each with their own private EHR databases. And these clinics don’t have an incentive to push for interoperability. “There isn’t necessarily a great reason for an individual clinic to want to adopt a system that can talk to another practice’s system,” says Shipman.

Indeed, in human medicine it took government intervention to push for interoperability—a fight that’s still ongoing today (see “Seeking Solutions: A Roadmap for Interoperability” below). “One big difference, I think, between veterinary medicine and human medicine is that there is a certain amount of government pressure to meet certain meaningful use standards,” says Shipman. “We don’t have those in veterinary medicine.”

There are also technical challenges that would need to be sorted out before true interoperability is even possible in veterinary medicine. “There’s no way to really standardize it at this point … Even if everyone said, ‘Ok, we want to share our data right now,’ well they use different terminologies, different abbreviations, and so it’s sort of garbage in, garbage out.”

So what happens now if a dog has cancer and needs to be seen by a specialist? “With my software system I can print up a chart, which is a PDF file, and I can just email it to them,” says Shipman. “It’s not a standardized file format where I can send a file and they upload it and it becomes part of their system. That would be ideal.” This is one advantage veterinarians have over human physicians: they do not need to follow strict privacy and confidentiality practices regulated under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

In fact, if it wanted to, the veterinary community could take advantage of another tool currently not used for human patients in the United States: the unique patient identifier. The unique patient identifier is a personal code used on all of a patient’s medical records—allowing these records to be virtually connected. Proponents of the unique patient identifier say it could help prevent fraud, streamline record-keeping and billing, and decrease medical errors and patient mix-ups. But detractors say that it impinges on patient privacy. (Originally, HIPAA called for the development of a unique identifier, but Congress deleted that part of the bill and banned the government from spending federal money on creating such an identifier.) With limited privacy concerns, veterinarians could develop a unique patient identifier, but, as with interoperability, there’s no incentive for individual veterinarians to do so.

[accordion title=”Seeking Solutions: A Roadmap for Interoperability”]

Pretty much everyone agrees that EHRs would work a lot better if information transfer in the healthcare sector were easier. To try to improve the state of data sharing, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) released a 77-page ‘interoperability roadmap’ in January 20153. The roadmap lays out detailed milestones and calls to action for the different elements needed to make interoperability possible—such as creating a supportive payment and regulatory environment and defining consistent data semantics and formats.

Why is the roadmap needed? “With EHRs there’s not a lot of standards in place or a framework to build up from and so we have a lot of vendors who have developed their solutions, hoping to get ahold of the market without the consideration of looking at exchanging data with other systems,” says Bill Ash, strategic program director for the IEEE Standards Association (Figure 4, right). He notes that some healthcare facilities even have interoperability problems within their own institutions.

But Ash says interoperability is fully possible. “The technology is there…From the framework side, they [the ONC] has a great starting point. The question is whether we can actually get the industry to move in that direction.”

There’s a lot to be gained from reaching the goals laid out in the ONC’s roadmap—both for individual patients who won’t have to cart their charts around—and for research. “Interoperability and the exchange of data really starts to help when we start looking at chronic diseases, we start looking at cancer, we start looking at medication and behavior,” says Ash. “We can actually take that data and turn it into information. And even start looking at predictive analytics.”

There are already signs of the predictive power of EHRs. A study conducted by Harvard researchers and athenahealth found that EHR data, when combined with historical epidemiological information, was able to predict regional flu outbreaks better than the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Google’s Flu Trends estimator [1].

References

- Santillana M, Nguyen AT, Louie T, Zink A, Gray J, Sung I, Brownstein JS. Cloud-based Electronic Health Records for Real-time, Region-specific Influenza Surveillance. Sci Rep. 2016 May 11;6:25732. doi: 10.1038/srep25732

[/accordion]

The Human Case for Better Animal EVHRs

There is a very good reason for people who are interested in human medicine to support better EVHRs: some animal diseases can make people sick. According to the CDC, tens of thousands of Americans get sick from diseases caught from animals—also called zoonotic diseases—and three out of five newly identified diseases are zoonotic diseases [5]. While veterinarians and agricultural producers have reporting requirements, these can vary by state, meaning a bird flu outbreak in one state might be caught faster than an outbreak in another state. “If our systems were just routinely collecting and aggregating more of these data, we would be able to both start our response faster and, more importantly, carry out those response efforts a lot faster,” says Michael K. Martin, DVM, MPH, DACVPM of Clemson Livestock Poultry Health.

As it stands now, electronic health records for agricultural animals vary by producer, state, and type of animal. For example, the pork industry has voluntarily created the Swine Health Information Center [6]. But when a cow is diagnosed with bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease), livestock investigators often have to sort through paperwork and interview farmers to try to piece together where that cow came from and which other cows had been exposed to the same sources—who might also be infected. “In my world, the ideal animal record would include those types of records as part of our longitudinal animal health record and we would know that they moved from here to here and they were tested for this disease on this date,” says Martin. “Those records are sorely lacking at this point.”

Interestingly, a fight in the agricultural world mirrors the unique patient identifier debate from the 90s. In the early 2000s there was a proposal called the US Animal Identification Plan that would have required every cow and other large agricultural animal to get an electronic ear tag near the time of its birth that could track that animal through its entire life. “It was received in exactly the same way the national [or unique] patient identifier was, that we recognize that you could do all these wonderful things if you had this, but it’s just too invasive of farmer privacy.”

Zoos: An EHR Success Story?

What would EHRs look like in a land where seamless interoperability and unique patient identifiers were de rigueur rather than pie in the sky fantasies?

Almost 1000 zoos and aquariums in nearly 90 countries use a web-based program called the Zoological Information Management System (ZIMS) created by the non-profit International Species Information System [7], ZIMS allows staff members at these institutions to create husbandry and medical records for all of their animals and to share these records when animals are moved from one institution to another.

This means that when a tree kangaroo is sent from a zoo in Seattle to a zoo in Rhode Island, the animal’s new veterinarians can see all of the animal’s past blood work, prescriptions, and clinical notes. One thing that helps make this sharing seamless is that all animals in ZIMS have a global accession number that they keep forever—very much akin to a unique patient identifier.

ZIMS, like all software, isn’t perfect. “It’s constantly developing,” says Mike McBride, DVM, director of veterinary services at the Roger Williams Park Zoo in Providence, Rhode Island. “Sometimes we wish it did things differently or better but there are reasons either good or bad why they chose to do things certain other ways—sometimes we just have to adapt to the system that we have.”

Each new version of the ZIMS contains new features that take advantage of the data-collection and sharing possible via a web-based system. For example, the program automatically creates crowdsourced reference intervals for blood work for different species. And another crowdfunded tool was just recently released: global anesthesia summaries. “We can select a species and then we can run a search and it will summarize for us all of the different drug protocols, who’s used them, at what dose ranges, what were some of the side effects,” explains McBride.

But even with increased data-sharing and reports, it is difficult to encapsulate the art of medicine in an electronic record—a sentiment shared by many human clinicians and veterinarians. “What’s written in the medical record is the bare minimum but doesn’t necessarily always tell you all of the picture,” explains McBride. “There may be things outside the animal’s specific condition—maybe the weather that day made you make a certain decision—you can never remember to put all that info in there. Being able to still have that one on one conversation with the other veterinarians is still important.”

References

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ‘Office-based Physician Electronic Health Record Adoption: 2004-2014,’ Health IT Quick-Stat #50. September 2015.

- Survey of Physicians Shows Declining Satisfaction with Electronic Health Records.

- Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology. ‘Connecting Health and Care for the Nation: A Shared Nationwide Interoperability Roadmap’.

- Krone LM, Brown CM, Lindenmayer JM. Survey of electronic veterinary medical record adoption and use by independent small animal veterinary medical practices in Massachusetts. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014 Aug 1;245(3):324-32. doi: 10.2460/javma.245.3.324.

- CDC and Zoonotic Disease Fact Sheet.

- Swine Health Information Center.

- The Zoological Information Management System.