What does intelligence mean for a hospital where the main problems aren’t incompatible computer systems and data overload but a lack of computers, of trained personnel, or even of basic resources such as clean water and pharmaceuticals?

There are still many parts of the world, including much of Africa and India, where patients live 30, 50, or even 100 miles from the nearest health center and where the existing hospitals offer dank, enclosed waiting rooms that do as much to spread disease as cure it. But these challenges don’t preclude opportunities in these regions for smart care delivery. On the contrary, the very lack of resources can be an advantage—there are no concerns about unwieldy infrastructure in aging buildings, manned by staff long set in their ways. These regions have urgent health needs and crises, yes, but they also have a wide-open playing field in which to start addressing them.

“What we’re starting to see is that the type of ecosystem where the resource constraints are felt more severely and the health needs are also more palpable is one in which more transformative types of innovation are possible than perhaps what we think of as typical health innovation in a U.S. or developed-economy context,” says Krishna Udayakumar, the executive director of the International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery, cofounded by the World Economic Forum, McKinsey & Company, and Duke University.

So what do these hospitals look like? In some cases, it looks like a hospital that runs more like a big-box retail store than a health care system—with prices to match its poorest patients. In others, it’s strategically placed windows and fans or inexpensive new tools that coax a culture change among staff. Sometimes, it’s a hospital that’s been taken entirely out of its traditional building and rebuilt—insurance-processing capabilities and all—onto a US$10 cell phone that goes where it’s needed most. It’s intelligent care that redefines what it means for a hospital to be “smart.”

Constructed Intelligence

The wards of Butaro Hospital in Rwanda’s northern Burera District are airy and light, filled with natural sunlight and brightly painted accent walls. Patient beds line the center of the rooms, facing windows that look out either onto a spectacular vista of green mountains or onto a landscaped inner courtyard. There is no one all-purpose building here, rather, the hospital is divided into a series of smaller structures—an emergency department, an intensive care unit, a women’s ward, and so on—each with sloped, rust-colored terra cotta roofs and white concrete walls. Here and there, neatly fitted stone walls fashioned from volcanic rock lend a touch of rustic elegance.

It’s beautiful, yes, but it’s also more than that. This hospital was designed by the Boston, Massachusetts-based architecture firm MASS Design Group in collaboration with the internationally renowned Partners in Health organization and the Rwandan Ministry of Health. Through design alone, the structure actively discourages the spread of airborne diseases: the dispersed buildings and courtyard scatter patients into the open, eliminating the crowded hallways and enclosed waiting rooms of traditional hospitals. The placement of beds in the center of the wards allows for larger, multilevel windows that pull a steady flow of air from outside, while strategically placed low-speed fans pull that air upward toward disinfecting ultraviolet lights for a third layer of sanitation that comes with minimal electrical demand. Even the floors are an easy-to-clean continuous sheet of epoxy. And as for the volcanic rock walls—well, even beauty has its place in a setting meant for healing.

“A building can improve or reduce health,” says Michael Murphy, cofounder and executive director of MASS Design Group. “At a very fundamental level, the building is part of your health care delivery program.”

Many hospitals in both developing and developed countries, he explains, neglect this concept. One specialist usually designs the building, and another fills it with the mechanical systems that make it run, neither giving much thought to how the other’s work will interact with theirs, much less how the end structure will interact with the surrounding environment. This type of unintegrated design is particularly risky in poorer nations where hospitals might be built along the lines of a traditional Western building—enclosed waiting rooms, hallways, and mechanical ventilation systems—but without the same resources to maintain them properly. “So immediately you know the mechanical system will fail. And what is a building with a failed mechanical system? It’s not a well-functioning building,” Murphy says. “In fact, it’s a dangerous building.”

Murphy says that it’s hard to quantify the precise impact of his hospital—it is one of many changes that have taken place in Rwanda. But that said, before Butaro was built, the Burera region had some of the worst health figures in the world and no district hospital at all. Within just its first year of operations, the hospital treated 16,638 outpatients and 7,206 inpatients for everything from tuberculosis to cancer, successfully cared for 230 ill and premature infants, and helped 941 women give birth—416 of those by cesarean—and only one of the 941 women did not survive.

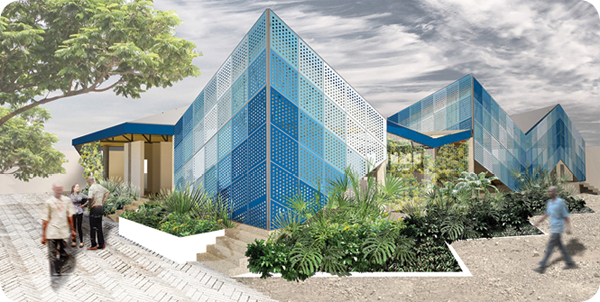

Butaro was the MASS Design Group’s inaugural project. Now, three years since its doors opened, Murphy’s team is in high demand and working in ten different countries. At every facility, as with Butaro, the crew zeros in on a single problem and attacks it from multiple angles. At the GHESKIO Cholera Treatment Center under construction in Haiti, the issue is waterborne contamination, which means that, from the start, the priorities are safe water and heavy-duty cleaning (see “Haiti’s GHESKIO Cholera Treatment Center”). Thus, the resulting design includes an on-site mini wastewater-treatment facility that harvests and purifies rainwater to use for frequent cleanings, floors that are easy to mop and outfitted with drains leading directly to the treatment plant, and sinks that are deep and wide to minimize splashing.

[accordion title=”Haiti’s GHESKIO Cholera Treatment Center”]

Haiti’s GHESKIO Cholera Treatment Center, designed by the MASS Design Group and currently under construction, includes features like the walls shown in the second and third images, which optimize airflow while preserving patient privacy and dignity: at top, a rendering of the center’s exterior, second, a rendering of the interior, and third, the interior screens during construction. (Images courtesy of MASS Design Group.)

[/accordion]

The group has also recently designed an alternative approach to minimize airborne diseases at the Nyanza Maternity Hospital, also in Rwanda. Here, because the site sits in a valley instead of on a hilltop, the crew has invented what they call solar chimneys to passively pull the air out and up from the wards, creating an entirely natural forced-air ventilation system. (Construction has not yet begun as project partners continue to search for funding to break ground.)

“Our long-term goal is to continue to use architecture to fundamentally improve people’s lives—and to prove that it does,” says Murphy. Architects, he says, need to start asking harder questions about their creations. “What is the impact of what we do?” he asks. “Are you designing for efficiency alone, or are you designing for health outcomes?”

Assembly-Line Economics

Each surgeon at Narayana Health’s flagship 1,000-bed cardiac center in Bangalore, India, shown above, performs an average of two to three surgeries a day, six days a week, adding up to easily several hundred in a year. The entire Narayana hospital system, including 6,900 beds in 26 hospitals throughout the country, accounts for 10–12% of all of India’s heart surgeries; a growing portion of its eye, kidney, primary health, and cancer interventions; and, so far, over 50,000 remote consultations with patients in India, Africa, and beyond. To compare, the typical surgeon in the United States performs 100–200 cardiac surgeries in a year, one of England’s largest cardiac hospitals has 270 beds and 58 operations a week, and both countries perform their services at ten times or more the cost at Narayana. It is the Ford factory line, the Amazon, and the Walmart of health care all rolled into one.

At the core of Narayana’s extraordinary prolificacy is its business model. Surgeries are streamlined into an assembly line, with junior surgeons opening and closing patients, primary surgeons stepping in only for the main intervention—maybe an hour’s work or so—and support staff wrangling the worst of the paperwork. Next, there’s the sliding pay scale, wherein wealthier customers can opt for standard or luxury care packages that might include various amenities like a private room, but at triple the usual price. That, in turn, is accompanied by ruthless cost-cutting—a few years back, for instance, hospital stitches once bought at an international medical supplies subsidiary for US$100,000 a year were swapped out for comparable versions made by a Mumbai company for half the price. Narayana also negotiates pay-per-use prices for medical equipment, sterilizes and reuses normally single-use tools like steel clamps (saving US$160 a clamp), barcodes all inventory for tracking, and pays doctors fixed salaries instead of a per-service fee.

Finally, all of this information streams into a cloud-based database that creates a near-real-time picture of the entire Narayana hospital system’s profits and losses. Every day, doctors and administrators receive a text with the previous day’s performance, right down to how an individual’s choice of medication or instrument affected the bottom line. “If you look at the balance sheet at the end of the month, it is like reading a postmortem report,” explains Devi Shetty, Narayana Health’s founder and chair. “But looking at it on a daily basis is like a diagnostic tool—you can do something to salvage things.”

What they are salvaging is not their own pockets but the ability to maintain the level of funds the hospital system requires to provide its services to anybody who needs help—whether they can pay in full or not at all. “It is pointless to be talking about all the developments in health care if 90% of the world’s population can’t afford it,” Shetty says. Health care expenses are a major cause of bankruptcy in India, putting 20 million Indians below the poverty line every year. At the same time, the country also experiences some of the highest rates of cardiac problems in the world, accounting for 45% of global coronary heart disease and requiring some 2 million heart surgeries every year. Among all the available hospitals in the country, however, maybe 120,000 are actually performed. Of the remaining 1.9 million—”we produce one of the largest numbers of young widows in the world,” Shetty says.

The average price of a heart procedure at Narayana is between US$1,500 to US$2,000—a fraction of the typical US$20,000–US$100,000 that accompanies such a procedure elsewhere in the world. Every month, 20–40% of their services are provided at a discount, and some are given entirely for free, cross-subsidized by those wealthier patients who choose to pay more. Perhaps more remarkable still, this does not come at the cost of quality: Narayana’s mortality and complications rates are on par with international standards. Its infection and mortality rate for one of the most common procedures, the coronary bypass graft, are around 1 and 1.27%, respectively, essentially comparable to U.S. rates of 1 and 1.2%.

Narayana turns 13 years old this year, and its two constant themes are growth and improvement. It has just opened a new 140-bed branch on the Cayman Islands to treat poor Caribbean residents and perhaps wealthy Americans from the nearby Florida coast. Over the next ten years, that outpost is meant to grow into a multispecialty, 2,000-bed health city. Back in India, the hospital complex has plans to expand from 6,000 to 30,000 beds across the country, with the ultimate goal of a US$800 price point for a major heart operation. Emerging initiatives are currently underway to help reach that point, including a shift from paper-based data entry to iPad systems as well as a low-cost hospital design that uses prefabricated structures and natural daylight and ventilation to cut the average cost of a bed by half or even a third of its current price.

[accordion title=”Mobilizing Infrastructure”]

Sometimes, it almost doesn’t matter how intelligent a hospital is—it simply won’t be enough to reach all the people who actually need it. India needs to add at least another 1.75 million hospital beds, and some estimates say it actually needs twice that. Over 80% of Rwanda’s population lives in rural areas, often more than a three-hour walk from any sort of clinic, and in the tuberculosis-and HIV-fraught Namitete region of Malawi, one hospital—St. Gabriel’s—serves a quarter of a million people.

But what these regions lack in hospitals, they make up for in cell phones. According to the United Nations (UN) Telecommunication Development Sector, mobile phone penetration in developing countries will hit 90% by the end of 2014. That fact opens the door to new models of care that turn the hospital inside out, putting everything from patient records, to diagnostic support, to insurance processing onto the phone, and then dispersing that technology far into communities where, in some cases, no doctor has been before.

“What we’ve seen is really a change of mind-set—going away from thinking of health care as services that are based in clinics and hospitals per se, to thinking about health services more broadly as ways to support patients and their families and communities,” says the International Partnership for Innovative Healthcare Delivery’s Krishna Udayakumar. “The most intelligent hospitals of the future are really going to be those that aren’t hospitals at all.”

The San Francisco, California-based Medic Mobile offers a relatively simple variant of this idea. Founded in 2009 by then Stanford undergraduate Josh Nesbit, the company has created a sort of go-anywhere health communications network based on community health workers and their phones. The key is in a parallel SIM card that the company developed, which piggybacks the Medic Mobile medical app onto any phone, regardless of provider. Thus, instead of gathering health information over time and walking for hours, if not entire days, to update the nearest hospital, community representatives can use the app to send real-time notices and questions and receive, in turn, support in the form of checklists, appointment reminders, and advice.

In one early trial with the overwhelmed St. Gabriel’s in Malawi, 75 community health workers armed with Medic Mobile-enhanced phones were able to double the number of people with tuberculosis symptoms referred to the facility, and they identified another 130 individuals with various life-threatening issues for immediate treatment. By the end of that six-month period, 1,330 messages had been sent, and researchers estimate that the updates saved the hospital staff over 2,000 hours of unnecessary follow-up time and US$3,000 in fuel costs.

Other versions of such dispersed health care take the concept a step further. Several innovators have begun to establish networks of semimobile, bare-bones clinics throughout rural parts of Africa. One Family Health (OFH), for instance, is a U.S.- and Europe-based organization operating in Rwanda that has translated the McDonald’s franchising concept from hamburgers to health care. In this case, the business (clinic) owners are nurses, the services are treatments for the most common causes of preventable death among Rwandans—malaria, malnutrition, diarrhea, etc.—and the target populations are the regions of the country located more than a three-hour walk from existing hospitals and clinics.

The North Star Alliance takes a similar approach to OFH, though its roots and resulting strategy are in shipping and logistics. It was cofounded in 2006 by the distribution company TNT Express with the UN’s World Food Program to counter the devastation that HIV had wrought on its truck drivers, who rarely had the opportunity to ever see a clinician. Over the course of the past few years, the Alliance has created a tightly organized system of clinics crafted from repurposed shipping containers and deployed across truck stops and border crossings of over a dozen different African nations, where they provide primary care and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases as well as counseling to drivers and sex workers.

As with Medic Mobile, the backbone of each of these programs is in the technology. OFH runs off a mobile phone application that can create electronic health records; guide the nurse through visits and diagnoses; process insurance claims; track pharmaceutical prescriptions, inventory, and expiration dates; and even help with quality-control standards by sending all of that information back to the OFH central offices for oversight. It’s quite nearly a hospital’s worth of information technology in the pocket of every nurse. North Star’s network, meanwhile, centers around a laptop-based “health passport” system, which creates health records able to follow patients across borders to any other clinic outposts. A new software initiative just launched by the company this year will add to that concept by allowing the Alliance to analyze information, such as how diseases spread and where people move, to help organizers figure out the best possible place for a new clinic.

“It actually allows us to run various models considering things like, if we want to rig the system for optimal continuity of care, it might look like this, and if we want to center in one particular disease, such as HIV, then it might look like this,” explains North Star Alliance Executive Director Luke Disney. True to the Alliance’s roots, he explains, the program is built on a commercial logistics platform, and relies largely on organization. “Just like UPS would think about what’s the most efficient way of getting from A to B, we do the same thing: Where’s the most efficient place for us to position our services, related to our customers and clients?”

The lightweight infrastructure of all three approaches has allowed them to scale with breathtaking rapidity. By the end of last year, the five-year-old Medic Mobile was working with 7,836 community health workers, serving more than 5 million people in 21 countries around the world. The North Star Alliance is active in 13 countries across Africa and treating over a quarter of a million individuals, and OFH—which only reached its franchise agreement with the Rwandan Ministry of Health in 2012—already has 83 outposts throughout that country, with plans to grow to 500 or more by the end of 2018.

“Innovation begins with looking at something from a different perspective,” Disney says. “And we’ve had the distinct advantage of having a green field situation.” But, he points out, that doesn’t mean the concept couldn’t work elsewhere. “I think that innovation and health, whether in Africa or North America or Europe, is facing a number of similar situations where costs and technology and disease patterns and mobility are forcing us to reevaluate how we deliver and think about delivering services. It’s going to be more daunting for people in robust or established health systems to make change, but I think we all feel that it has to change, and it will change.

[/accordion]

“Today, health care is delivered as a hand-crafted masterpiece,” Shetty says. In other words, it’s expensive, slow, and inadequate for modern demands. Health, he believes, has the potential to drive the world’s economy in the 21st century, but to make that happen, caregivers and administrators have to treat it like a business, not an art. “We have to commodify it,” he says. “If the solution is not affordable, it is not a solution.”

Designed Behaviors

If a surgical team walks through a list of basic steps and information checks before and throughout a surgery, it doesn’t matter whether that team is in Seattle, Washington, or rural Tanzania: they can cut postsurgical deaths and complications in their hospital by 47 and 35%, respectively. It’s a concept made famous in 2009 by author–surgeon Atul Gawande in his book The Checklist Manifesto, and thanks to that work and collaborations with the World Health Organization, it has since become an operating room staple in over 4,000 hospitals around the world.

The key to the checklist, however, is not the list itself—it’s the way it changes the behaviors of the users. Take the questions it asks—Patient has confirmed identity? Surgeon, anesthesia professional, and nurse review the key concerns for recovery and management of this patient?—simple, yes, but the act of asking them correctly requires surgical teammates to introduce themselves, talk to one another, and focus their attention on the little details that can otherwise become rote and rushed. It softens the intimidating hierarchy of the operating room and standardizes best practices.

Cultivating better behaviors like this is low-hanging fruit when it comes to improving hospital function—easy to overlook, but also comparatively easy to implement. It can be particularly effective in impoverished regions, where care is uneven and minor changes to general practices can have enormous repercussions in patient outcome.

Ariadne Labs was launched on this principle two years ago by Gawande and several of his colleagues at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard School of Public Health, both in Boston, Massachusetts. It’s a health systems innovation center named for the Greek goddess who led Theseus through the Minotaur’s labyrinth with a thread. Its mission, aptly enough, is to find the health care equivalents to that thread—the simple tools and tweaks that will transform the way people do medicine.

“Adopting a technology causes a change in the culture,” explains Leonard D’Avolio, who directs the Informatics and Measurement Platform at Ariadne Labs. “What we do is leverage that and make it positive change.”

So far, the center has several major initiatives underway across the world, including the Safe Surgery program—which elaborates on the original surgical list in both wealthy and lower-income regions—and the BetterBirth program, which targets maternal and infant mortality primarily in developing parts of the world. Each currently centers around the checklist concept, though not entirely. “The easiest thing about a checklist is to make one,” D’Avolio says. “The hardest thing is to get people to actually use these very simple pieces of technology effectively.”

To that end, he explains, the center has integrated intensive education into these interventions. Part of the Safe Surgery operations in Sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, often entails providing hospitals with easy-to-use pulse oximeters (in partnership with the Lifebox Foundation, a nonprofit organization founded by Gawande with the goal of making surgery safer globally)—these are a necessary monitoring device on the surgery checklist but are often missing in rural African hospitals. To receive them, hospitals must also allow the team to give an anesthesiology course at the same time. “It’s an excuse to help train people to give safer anesthesia,” D’Avolio says.

The BetterBirth program, meanwhile, uses a basic 29-item list to confirm points like hand washing and the availability of necessary treatments like oxytocin, but it bolsters that list with coaching and real-time mobile support to make sure the new practices stick. So far, it’s worked: pilot trials on that front in Uttar Pradesh, India, have reported that the intervention boosted rates of practices like hand washing before initial vaginal exams from 1 to 98%, and a broader study is underway now.

Applications for behavioral designs like these don’t stop at developing regions. The surgical checklist, for instance, is actually better known for its positive effects in Western operating rooms. In fact, behavioral modulators can be ideal solutions in modern hospitals because they can be retrofitted into pre-existing systems for minimal cost. In U.K. hospitals, for instance, subtle environmental and design cues gained momentum as a way to counter poor patient participation in screenings or moderate violence in waiting rooms.

The idea, explains Dominic King, a surgeon at the Imperial College of London and clinical lead of a new health care design initiative between the college and the neighboring Royal College of Art, is called behavioral design. “You’re taking very basic insights from psychology and behavioral economics—for example, people tend to stick with default options or respond to things that are novel or seem relevant to them—and then designing a product or a service around them.” Retailers have known this for years, which is why the pricey, brand-name cereals are so often at eye-level in the grocery store, but King sees the real potential for this concept in health care. “You can think of the hospital as almost the most complex building you could have in a community,” he says. “You’ve got lots of things going on, you’ve got nuclear medicine, you have operating theaters. It’s inherently complex, and there’s a lot that design could do to make things easier for people.”

In 2011, the United Kingdom’s government-established Design Council (now independent) and its Department of Health teamed up to tackle the issue of aggression in Accident and Emergency departments (A&Es)—a £69 million a year problem in U.K. hospitals. After researching the situation, the team discovered that a major trigger for aggression was the way the emergency room processes left the patients in the dark. People showed up, expected to wait, be seen, treated, then leave—but what usually happened is that people would wait, see a nurse for a few minutes, wait some more, see someone else, and so on.

“People can feel they’ve been forgotten about, or that they’re in the wrong place, and this can cause additional anxiety at a time when they’re also experiencing pain and fear,” explains Catherine Pratt, a project manager at the Design Council who co-led the project. The harsh styling that some A&Es can have, with chairs bolted to the floor and glass barriers separating the receptionist from the visitors, only exacerbates that state. “So much so,” says Pratt, “that someone who would normally manage their behavior is much more likely to become violent or aggressive when put in that context.”

The Design Council posed the problem as a nationwide competition, which was won by a team led by design company PearsonLloyd. Their solution included signs that break down the A&E process, training staff members to better greet and manage visitors and patients, as well as design tips on lighting and seating, including making chairs more comfortable and arranging them into groups. Simple, but like the surgical checklist, effective: in the intervention’s two pilot hospitals in London and Southampton, threatening body language from visitors dropped by 50%, shouting and raised voices dropped by a quarter, and 75% of patients reported feeling less frustrated. It was inexpensive too—the implementation cost £65,000, and researchers estimated that the hospitals gained £3 in benefits for every £1 spent. As of fall 2014, at least five other hospital networks in the United Kingdom have implemented the changes in their A&Es, and another ten are exploring the idea of installing smaller variations on the idea.

Successes such as this have also helped to spur design even further into U.K. health care. Last fall, the Royal College of Art kicked off a collaboration with the Imperial College of London to form the Health Care Innovation Exchange (HELIX). HELIX brings together designers and behavioral psychologists and embeds them in London’s St. Mary’s Hospital (one of the Imperial College’s academic hospitals) to interact directly with clinicians and patients and start addressing weak points. One of the first projects included a revamped bowel cancer–screening kit sent to aging patients, making it both easier to use and a lot less frightening (less you are now at risk for bowel cancer and more the odds of cancer are very small, but the benefits of testing are very high). Efforts to implement and assess the project on a large scale in England are also underway, and, in the meantime, the group is working on creating more engaging asthma-management tools for children and trying to reduce the number of different hospitals to which patients with chronic diseases are sent.

“We’re not inventing new technology,” says HELIX Designer Maja Kecman of the work. Rather, she explains, they’re designing experiences. “Even if we’re designing a product, we always have to think about the whole experience of the user that’s going to ultimately use the product,” she says. “It’s part of a whole ecosystem, and health care’s particularly complex.”