Back in 2004, Scott Johnson, a type 1 diabetic, could find plenty of online information about the symptoms and complications of the disease that prevents his body from producing the blood-sugar-regulating hormone insulin. What he couldn’t find was anything written by someone actually living with his disease. So he started his own blog, eventually attracting thousands of page views a month. His blog became a place where he could share stories with other diabetics and find support, encouragement, and even a sense of normalcy.

“Diabetes is, for the most part, invisible,” says Johnson. “I wouldn’t know someone had diabetes unless they told me. It’s very isolating to have to do extra work to survive every day and not be able to talk with others who understand.”

As the prevalence of diabetes continues to grow worldwide, researchers and patients like Johnson are increasingly turning to a growing number of social networks, online support groups, and mobile apps to help them manage a disease in which it is especially important to keep track of carbohydrate intake, blood sugar levels, and insulin injections. Apps in particular are becoming an important way for patients to more easily log and contextualize the complex balance of diet, exercise, and insulin needed to maintain normal blood sugar levels. More open data collection and analysis through apps and online systems may also help researchers better understand and track demographic trends underlying the disease.

“The mobile phone is a landmark for diabetes,” says Jennifer Dyer, M.D., a pediatric endocrinologist and creator of the EndoGoal diabetes management app, which rewards users for checking their blood sugar. “It offers convenience and portability for diabetes data management, it has your social media connections, and it offers other opportunities to connect diabetes to other parts of your life.”

There are challenges. Many of the diabetes-monitoring technologies—glucose meters and insulin pumps—have proprietary platforms that don’t talk to each other, interface well with smartphones, or give patients and providers user-friendly access to the full spectrum of data. But as the industry sees larger patient and provider demand for more open, useful data, this is starting to change.

Clinical Recommendations and the Messy Interoperability of Devices

Last year, Johnson joined the MySugr team, an Austrian app company that offers one of the few U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved diabetes management apps for Android and iOS operating systems. The app has attracted more than 86,000 users since its inception in 2011 and winning of FDA approval in 2013 (Figure 1). The MySugr app encourages patients to enter health data by rewarding them with points that “tame the diabetes monster,” a metered representation of how well the patient is logging data (Figure 2). The app then interprets blood glucose information and user data in easy-to-digest charts and graphs and offers encouragement and goal-setting features.

Despite the app’s success, the lack of interoperability between diabetes devices and apps presents a challenge to companies like MySugr and others in bridging the gap between data, communication, and patient usability. When patients have a blood glucose reader, insulin maker, and cell phone that can’t talk to each other, patients are saddled with the time-consuming burden of logging their own data, which often leads to errors.

“If devices such as the glucose meter, insulin pump, insulin pen, and the software to read all of the data at a glance could be interconnected into one platform, it would be incredibly powerful,” says Dyer. “It’s like dealing with VCR, TV, and Xbox remotes when you want a universal remote.”

Some companies have started to move toward this integration, as creators like ActiveCare, iHealth, LifeScan, and others offer wireless glucose meters with Bluetooth connectivity. Other app developers ask patients to input their own data to avoid the lack of interoperability.

One company has gone as far as to create its own way of connecting with the majority of devices to assist patients with health data logging. The Silicon Valley-based diabetes platform developer Glooko developed an FDA-approved app and cable that connects between 28 types of mobile phones and 29 types of glucose meters, which account for roughly 85% of the existing meter market, according to Glooko CEO Rick Atlinger (Figure 3). The MeterSync cable, which contains a microprocessor, memory chip, and battery, and runs about US$40, pulls historic data from diabetes devices and displays them in a free Glooko app within “30 seconds.” The app then allows users to select food and medication information to assist with logging. Data are also pulled into a cloud where providers or caretakers—anyone the patient gives permission to—can access it, offering patients and caregivers the potential for real-time health alerts to respond to emergencies.

“By illustrating this data, you can look back at data clusters and see if there are any patterns, such as any times of day when blood glucose levels get out of control,” says Atlinger, who adds that the app has thousands of users and focuses on both type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

In January 2014, Glooko and the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston announced a partnership to introduce a hybrid platform to patients and providers. The Joslin Diabetes Center, which sees around 25,000 patients, aims to bring mobile information to both type 1 and 2 diabetes patients and clinicians,says Harry Mitchell, executive director of the Joslin Institute for Technology Translation. The center is developing pattern-based algorithms that will interface with glucose readings to provide information related to potential hypoglycemia events, where blood sugar levels fall dangerously low and can lead to unconsciousness, seizures, and potentially death. Hypoglycemia is the type of incident that constant monitoring and predictive software could help prevent, e.g., by sending an emergency notice to the patient or caretakers.

“Providing real-time data will improve efficient and effective communications between physicians and patients. Doctors will have more timely and relevant information to review, and patients will feel more engaged with managing their diabetes,” says Mitchell. Glooko and Joslin are currently rolling out the system to patients and clinicians in the Boston location.

The Glooko system doesn’t make medication recommendations, but rather, through the collaboration with Joslin, will learn to look for patterns in patient data, provide behavioral prompts to patients, and summarize historical data for review by clinicians. “The Joslin/Glooko system is not developed for the purpose of practicing medicine using mobile devices. We’re trying to get the right data for review by the patient and clinician to have an impact on diabetes care, resulting in a favorable impact on health care costs,” adds Mitchell.

Another platform, which offers the first prescription-only app, strives to make clinical recommendations based on users’ experiences. Last June, WellDoc, a Baltimore-based company that creates chronic disease management software, announced its BlueStar app, which is FDA approved for adults with type 2 diabetes and will be available this year. A doctor prescribes BlueStar to a patient, whose pharmacy alerts WellDoc to set up the account for the patient and provider. BlueStar analyzes a patient’s medical data—including blood sugar readings, medication, diet, and exercise—and offers personalized recommendations and behavioral coaching. It also sends contextualized information to providers to help assist with providing care. As for interoperability hurdles, BlueStar does not interface with diabetes technology at the moment but asks patients to log data.

An Open Movement

One thing that has been missing to tie apps and the technology together is a more universal software platform. The Silicon Valley start-up Tidepool aims to fill this gap by being the first open-source system meant for diabetes management.

“Type 1 diabetes is really the only disease where the doctor prescribes a deadly hormone—insulin, which can lead to seizures, comas, or death—and gives you general guidelines on how to take it, but you’re partially on your own to figure out hour-by-hour how much of this deadly hormone to give yourself,” says Howard Look, CEO of Tidepool. Look, who helped found TiVo and developed major products for Pixar and Amazon, banded together to found Tidepool with computer scientist and entrepreneur Steve McCann. Both have teenage daughters with type 1 diabetes. The nonprofit organization of 11 people (seven of whom have diabetes) is creating what Look calls the “first open-source open platform that makes it easier to get data from diabetes devices.” “We’re hopeful that’s going to help researchers in the diabetes space come up with better therapy recommendations,”says Look, who was also involved in developing two apps: blip, which provides snapshots of integrated behavioral data and Nutshell, which lets users log how they react to insulin dosing and meals, with the goal of making it easier to adjust doses in the future.

But the ultimate goal for Tidepool’s platform is to enable the use of closed-loop systems currently in development in the hopes of creating an automatic glucose meter and insulin pump. “We want to write great software that helps accelerate trials and commercialization of the artificial pancreas,” says Look.

A Panacea for Diabetes Management

The closed-loop system, commonly known as an artificial or bionic pancreas, promises to take the decision-making burden fully off the patient by connecting an insulin pump, a glucose monitoring system, and intelligent software to make the delivery of insulin automated and ideally improving over time. Manycompanies and universities are working on prototypes, slowly making headway toward a consumer product.

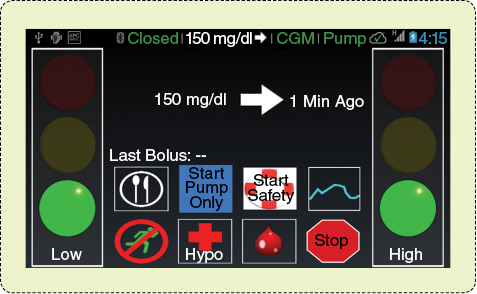

A team at the University of Virginia, which has worked on the closed-loop system for almost a decade, strips an Android phone of its features and uploads over a dozen apps that typically use Bluetooth for interconnectivity with major pump brands. The team has already built software ready to interface with the Tidepool

system.

“Presenting data by itself is not terribly useful to people at first; plots and graphs are cool, but what do you do with that?” says Patrick Keith-Hynes, assistant research professor at the Center for Diabetes Technology at the University of Virginia, one of the groups working on a closed-loop system. “But things that can function as a warning system would be incredibly useful. One of the things our system does in real time is estimate the risk for too high and too low blood sugar.”

As an example of the closed-loop system, the University of Virginia’s Diabetes Assistant (DiAs) rests on a stripped-down Android and uses Bluetooth connectivity to monitor blood sugar and insulin balance (Figure 4). If it predicts a hypoglycemic emergency, within 20 minutes, it will cut all insulin and sound an alarm. The alerts are also transmitted to cloud and database systems and can be forwarded to alert parents, partners, or physicians of emergency situations. The team plans to test the system on a large scale—with 50 patients and for a two-week period at home—this summer and will also run DiAs on Google Glass, where it can visually or vocally alert the user of an impending health emergency (Figure 5).

So will these and other closed-loop systems negate the need for sophisticated apps that offer to assist patients with diabetes management?

“Right now, nothing is available to consumers, but that will change in a few years,” says Keith-Hynes. He adds that the automated systems are more for type 1 diabetics, who must constantly account for the insulin their bodies do not make. Type 2, which makes up around 90% of cases, is often associated with obesity, lack of exercise, age, and other factors. Although those with type 2 must also keep track of health factors to avoid complications, the disease can typically be controlled by diet and exercise. “Type 2 is bigger and more complicated, and different systems might be helpful,” says Keith-Hynes.

Once closed-loop systems are commercialized, apps will still be needed to assist with monitoring. And not everyone will trust a closed-loop system right away or, as Keith-Hynes points out, even have a need for it if they are already managing their disease effectively.

Mining Through Data

With the rise of smarter apps and cloud storage, more knowledge about patterns and particularities of the disease will come from combing through aggregate data in a secure and anonymized fashion. Some companies already do this. Medtronic’s CareLink aggregates a patient’s own data and offers FDA-approved analysis to physicians regarding their patients’ patterns. And Unitio’s TD1 Exchange, MyGlu platform, combines an online community and aggregate patient outcomes with the goal of increasing drug development.

“It turns out that outcomes in clinical care for diabetes are not as great as we’d expect, based on data from academic research papers,” says Aaron Kowalski, M.D. and vice president of treatment therapies at JDRF, a global nonprofit that funds type 1 diabetes research. “This lets us go to the FDA and ask to move therapies along faster because the need is greater than we thought.” Kowalski, who has type 1 diabetes, says aggregate data can also reveal other areas for public health efforts to focus on, such as a trend of teenagers not taking insulin to not gain weight, at a risk of medical emergencies.

“The hope is that systems like the artificial pancreas, predictive apps, and intelligent aggregators can comb through that data and give people real useful concrete advice,” adds Johnson. “They will tease out the longer patterns and recognize trouble spots to make life easier for everyone with diabetes.”

Recommended Online Resources

Communities

- TuDiabetes

- Children with Diabetes

- American Diabetes Association Community

- TypeOneNation

- MyGlu

- Diabetic Connect

Blogs

- Diabetes Mine

- Sixuntilme

- The type2experience.com

- Ninjabetic.com

- Textingmypancreas.com

- Scott’s Diabetes