Turns out that studying zombie brains—among other age-appropriate topics—is a great way to engage and educate young students in the rudiments of brain science.

It’s early morning and the fog is lifting over the mountains. Several middle school students have been seen running into the school. What’s the hurry? Turns out there are zombies on the loose!

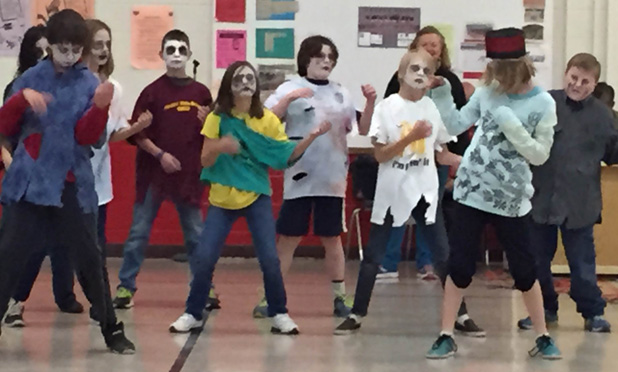

That is, student zombies preparing for the first public performance of the original play “Zombies Here, Zombies There… A Neuro-Thriller” by members of the Brain Hackers after-school club at Roosevelt Middle School in Tijeras, New Mexico. But this is not your typical Halloween horror production. Although the play focuses on a group of scientists who attempt to determine the cause and find a cure for the pandemic that renders 90% of the population doomed to a zombie-like affliction, the dialogue sounds much more like something you might hear in a university classroom.

For example, the debate between the actor scientists follows this vein:

Scientist 1: Maybe they’re just sleep walking. It could be like with a normal person. One brain circuit tells you to be awake and another tells you to be asleep, but you get stuck in between the two and walk around doing things with no awareness that you are doing them.

Scientist 3: Look at the way they walk. Their legs move, but it is crude and uncoordinated. It is as if the motor cortex is sending commands through the spinal cord to the legs, but there is no cerebellum to coordinate the movements.

Scientist 2: You’re right. It’s not like Parkinson’s disease where people have trouble initiating movement. That would suggest that there’s nothing wrong with their basal ganglia.

Scientist 3: There’s essentially no frontal lobes. Ordinarily, when a person gets angry, they can put on the brakes and hold themselves back, but with no frontal lobes, the brain circuits for anger and aggression go from 0 to 100 in the blink of an eye.

Scientist 2: There’s not much in the way of learning either. They pick up simple stimulus-response reactions, but that’s it. There’s sensory-motor learning, but their hippocampus is gone, so they are not able to form memories or learn from those memories.

Where did this language come from? According to Dr. Chris Forsythe, a neuroscientist at Sandia National Laboratories in Albuquerque, New Mexico, this is not what the typical middle school student learns in the classroom. In fact, even as schools nationwide attempt to bring more STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) to the curriculum, textbooks and teaching materials rarely focus on brain science despite the fact that neuroscience is one of the fastest growing fields. To remedy this, three years ago he founded the Brain Hackers after-school neuroscience program, which engages middle school students in learning about neurotechnology and applied brain and behavior science—sometimes in unconventional ways, including the study of zombie brains.

When asked why students are studying and writing about the zombie brain, Forsythe explains, “By looking at the zombie brain and asking what must be wrong to cause their behavior, it prompts students to think about how the normal brain operates to produce everyday behavior. This is a logic that is at the heart of neuropsychology where scientists, going back to Paul Broca in the 1800s, have inferred normal brain functioning based on observing what happens when there is damage to the brain due to injury or disease. Zombies offer a wonderful teaching tool because they are so prominent in pop culture.”

The students in the program collaborated with Forsythe to write the script, using Dr. Russell Morton’s (University of New Mexico Department of Neuroscience) “Brain of a Zombie” lecture as well as the book Do Zombies Dream of Undead Sheep by Timothy Verstynen and Bradley Voytek to provide inspiration. Forsythe also coordinated with professional performance artists, The Pink Flamingos, to help with production. In addition to this debut performance, the play will also be staged for the public at a local community center on October 30.

“Our current focus on zombies is consistent with the overall approach within Brain Hackers, which is to make brain science interesting and relevant by addressing topics and activities that are already on the student’s minds,” he adds. For the weekly meetings, Forsythe designs activities and lectures that naturally align with the teens’ interests, including music and the brain, the difference between boys’ and girls’ brains, understanding illusions, and how the brain constructs and responds to stories.

Students also learn to use EEG (electroencephalography) to observe and interpret their brain activity and create brain-controlled computer games. For one exercise, students monitored brain activity while playing musical instruments and analyzed the output, which was projected on a large screen. Activities like these not only expose students to the equipment and interfaces now available to monitor brain function, but also serve as a teaching tool for basic concepts such as pattern recognition.

Based on the number of students in the program, Brain Hackers would appear to be a success. In each of the first two years of the pilot, more than 50 students have participated, which accounts for one-seventh of the school population—an amount equivalent to the total number of students on the school’s sports teams. In addition, the club’s membership has consistently been 50% female, which is unusual in a middle school STEM-focused program.

And more interesting topics are slated for this school year. Last spring, students requested to learn more about artificial intelligence. To accomplish this, Forsythe has created a module where the students will first learn about different brain functions and associated brain circuitry and then attempt to model how the brain accomplishes the same functions using Lego Mindstorm robots. The robots offer a unique opportunity to create a software program that emulates a function and tests it in the real world.

As for the zombies, Forsythe hopes that the lessons learned extend beyond the knowledge of basic brain science the students display. “There are many moving parts to the stage production with each of the students having roles that are important to the overall outcome. With this, there is the understanding that when working as an individual I can have some notable accomplishments, but working as part of a large team, I can have extraordinary accomplishments. Despite all the emphasis on team sports and other team activities, many youth never really learn the fundamentals of teamwork, which are skills I believe serve as a multiplier to whatever successes the students might otherwise have based only on their knowledge, talent, and dedication.”

This just might be the type of zombie revolution we all can hope for.