Over the last decade, technology advances in the field of genetics have led to cheaper and more accurate testing. Public interest in personal genetics has grown thanks to media coverage and high-profile stories, such as actress Angelina Jolie’s decision to undergo a double mastectomy as a preventative measure against breast cancer when she learned she carries the BRCA1 mutation (relating to breast cancer type 1 susceptibility).

But attempts to be proactive in one’s healthcare through genomic screening can lead to frustrations. Many general practitioners aren’t trained in genetics and cannot answer specific questions, insurance may not cover a genetic test, and genetic counselors can have long wait times. So people are turning to the slew of companies offering genetic tests directly to consumers, bypassing the need to go through a clinic.

Easier access to genetic testing has potential upsides—for instance, being alerted that you have a greater chance of a disease allows you to take the appropriate actions. However, as “over-the-counter” genetic tests have become more readily available, consumers are facing potential pitfalls, most notably risks from misinterpretation and a loss of privacy.

The Boom in Consumer Marketing

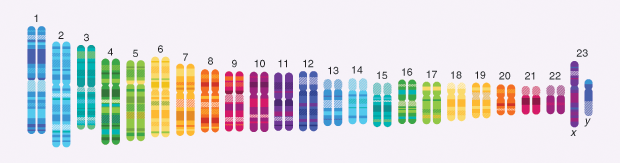

In 2010, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alerted several direct-to-consumer genetic testing companies marketing their products as ways to predict and mitigate health risk that such health kits were akin to medical devices and required federal approval. One of the most well-known personal genomics companies, 23andMe, made headlines in April 2017 for being the first direct-to-consumer test to receive FDA approval for ten genetic conditions (Parkinson’s, late-onset Alzheimer’s, celiac disease, and other conditions ranging from blood disorders to a movement disorder). The company tests approximately 650,000 areas in the genome (Figures 1 and 2).

“23andMe is the first and only direct-to-consumer genetics company to receive multiple FDA authorizations, including in the genetic health risk category,” says a 23andMe spokesperson. “Customers receive more than 70 reports that include information on health, genetic genealogy, wellness, and traits, things like lactose intolerance, caffeine consumption, and eye color.”

23andMe is far from the only genetic test on the market. AncestryDNA is well known for its lineage test, Futura Genetics uses genetics to point out major risk factors in lifestyle, and a host of other tests offer paternity or “infidelity” testing. And new companies seem to emerge constantly, such as Helix, an offshoot of genome-sequencing giant Illumina that launched in July 2017.

Helix aims to be the Apple app store of genetic tests by offering a suite of products, including National Geographic’s ancestry test and screens for family planning, fitness, nutrition, food sensitivity, and more (Figures 3–5). After a one-time sequencing of the full genome, Helix keeps the deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) information on hand, and customers can choose to share it as they purchase products from vetted third-party developers. Three of their products require a physician review to order tests that screen for gene variants associated with 64 genetic conditions like cystic fibrosis or Tay-Sachs or a hereditary state of high cholesterol; these tests also provide free access to genetic counselors to help consumers understand the data.

Yet despite the boom and popularity in personal genetic testing, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has been cautious about the usefulness of such tests, as indicated by a 2017 post on its website. “For the most part, data on personal genomic testing have revealed little or no harms but also little or no health benefits. Also, evidence on the ability of genetic information to change health behavior has been lacking,” according to Muin Khoury, director of the CDC’s Office of Public Health Genomics.

But companies argue that customers could benefit from having their data, even if it’s not fully utilized. “Helix believes that by making DNA sequencing accessible and relevant to people based on their unique interests, we can accelerate innovation and increase the personal and clinical utility of genomics,” says James Lu., M.D., Ph.D., a cofounder and senior vice president of Applied Genomics at Helix. “We believe information is power, and that your genetic data is an added layer of knowledge that you should be able to access and learn how it may impact your health and lifestyle. Whether or how that information changes a person’s decisions or behaviors should not invalidate the genomic test or the DNA insights it provides.”

23andMe, for example, points to a case study where one customer took an ancestry and health test and discovered that he was a carrier for an inherited form of hearing loss. “This is important information if/when [the customer] decides to start a family and will motivate him to have a discussion with his healthcare provider,” says a 23andMe spokesperson, adding that information discovered through consumer tests like this “can be a motivation to take steps to a healthier life.”

Reading the Genes

In general, genetic tests ordered through a doctor and ones available online are similar in accuracy for detecting differences in the DNA. But what really matters is the particular DNA each test is designed to analyze, whether that DNA provides useful information, and how the laboratory interprets the meaning of the DNA code. The cheaper tests that focus on a limited number of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) target common genetic differences that have little impact on disease risk, according to Wendy Chung, M.D., Ph.D. a professor of pediatrics and director of the clinical genetics program at Columbia University. However, sequencing tests that completely analyze one or more genes (assuming the genes are chosen correctly) can identify genetic differences with a much greater power to accurately predict disease risk.

“For some of these consumer products, there’s a sense that you may be getting a comprehensive genomic test looking at all 23 chromosomes, but there’s often a gap between the consumer’s understanding and the fine print,” says Gail Jarvik, Ph.D., M.D., who heads the Division of Medical Genetics at the University of Washington. “Most people don’t have the genetic knowledge to understand that a SNP array is not the same as full sequencing.”

This can be dangerous, says Jarvik, because it can lead people to a false assurance of health—something that is particularly concerning with patients who have a family history of genetic variants tied to breast or colon cancer not covered by a test. “We’ve had multiple instances of someone who has a family risk of certain genomic variants getting a consumer test result indicating they had a low risk for breast or colon cancer, but the test did not cover the specific variant in the family,” Jarvik explains. This can lead to patients who might become less attentive to check-ups, mistakenly believing their risk for a certain cancer is not elevated.

Other times, genetic test results have the opposite effect: rather than a false sense of security, consumers become distressed when they receive information suggesting they have a genetic variation tied to a slightly higher increase of a disease, such as Alzheimer’s.

Chung has encountered both issues with patients. “I’ve seen women with a strong family history of breast cancer who receive ‘normal’ results from consumer tests and thought they didn’t have to be so vigilant in their screening and preventative care,” she says. “On the other hand, I’ve also seen women who have had variants of uncertain significance—so not necessarily a pathological result—yet they might have a mastectomy thinking they had a mutation for a high risk of breast cancer and were taking the appropriate action.”

“Even when there is a positive association with a disease, genetic variants associated with disease increase the risk by two or three times rather than being able to say you have a 90% chance of getting this disease,” adds Jarvik. “We have a poor understanding of why genetic disease is variable across people.” Sickle cell disease, for example, is always caused by the same identifiable genetic variant yet can result in mild or severe symptoms within the same family.

Nevertheless, as the consumer tests become more affordable (many hitting around the US$100 mark), consumers will continue to be drawn to the tantalizing prospect of knowing the medical and historical secrets that lie in their DNA. Even if savvy consumers know how to correctly parse their results, however, direct-to-consumer genetic tests offer another potential pitfall: the loss of privacy.

More Data, More Problems

Even for the most aware customers, one murky question that surrounds direct-to-consumer testing is what happens to DNA data. Genetic testing through a consumer site is not treated in the same way as a test done through a clinic: in the United States, a test ordered through your doctor is subject to the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), legislation that aims to protect the privacy of medical data so they can’t easily be obtained by third parties.

This difference, it turns out, is monumental when it comes to privacy, according to Robert Gellman, a privacy and information policy consultant who focuses on health care. “A test from a consumer company is not HIPAA compliant, which means that the companies can often store a copy of your DNA indefinitely and sell data to marketers or pharmaceutical interests when they need to increase their bottom line,” he says, adding that privacy statements on consumer websites are often difficult to understand and frequently have a clause stating they are subject to change without notice.

Why does this matter? Genetic data offer a wealth of new information for marketers, pharmaceutical companies, and potentially even employers. And much like Google, genetic testing companies may initially say they won’t sell personal information but could change that in the future. “Your data that leak out from one place to another, one company to another, can easily end up in the hands of the marketing industry, which has enormously complicated detailed profiles of everyone in the United States,” claims Gellman. “[These] data can subtly affect your opportunities in the economic marketplace.”

Because genetic information is both more detailed and more easily misinterpreted, the consequences for skewed marketing are significant. If a genetic variant suggests a link to impulsiveness, for instance, marketers may hike prices on items for customers having the variant. “Targeted marketing can be a downside because you could get offers for things less likely to be in your interest and more in the interest of the marketer,” says Gellman. “For example, if you’re diabetic you may not get ads for life insurance but instead for lifetime annuity.”

And, he goes on, companies can indirectly give your data to outside parties; for example, a pharmaceutical sales department looking for 40-year-old white males with diabetes could pay a genetics testing company to have their ads target such customers. Based on the clicks from the ad links, the sales department can then reasonably infer that those customers have the traits they are looking for. What’s more, even if you yourself never get a DNA test, a family member’s test can contain information that applies to you; for example, a genetic variant on the Y chromosome found in the father is also applicable to the son. “If I know you have a gene for something, I may know something about all of your blood relatives with some degree of certainty,” says Gellman.

Aside from unwelcome marketing, genetic data can potentially be used in other problematic ways. While the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA) prohibits discrimination in health insurance and employment, some life and long-term care insurance companies ask for consent to obtain data as a condition of service. “Health or life insurers are likely to ask for your consent to obtain whatever data [are] available, including genetic data, and if you refuse consent they can refuse to write insurance,” says Anna Slomovic, Ph.D., a privacy consultant and researcher who has previously served as the chief privacy officer for several companies. “In some cases, the individual’s choice is either to give consent for an insurer to obtain the data or to go without insurance. And, if the Affordable Care Act is repealed and health insurance companies can once again discriminate on the basis of preexisting conditions, health insurance could become prohibitive, depending on your genetic test results.”

An employer’s knowledge of one’s genetic information could also present problems, even though employers are generally not allowed to investigate workers’ medical history. GINA prohibits employers from seeking out genetic information, except when employees voluntarily provide their genetic information to workplace wellness programs. However, workplace wellness programs can come with large financial incentives for participation. While employers must now balance the requirements of GINA and other laws when they define wellness incentives, a recently proposed House bill would make it easier for employers to offer large incentives for employee genetic information in wellness programs. This proposed legislation, strongly opposed by many consumer protection groups, may remove some of GINA protections.

Finally, while many direct-to-consumer companies state that they don’t sell individual personal data without permission, some do sell aggregate genetic information to pharmaceutical partners to study the data on a larger scale. But making DNA data fully anonymous is not as easy as one might think. “For their research purposes, companies say they use the data in an anonymized form. But it may not be possible to completely de-identify the data—data can often be linked with other data and re-identified,” explains Slomovic. “Aside from the data [themselves], the samples of saliva or blood are often kept and can be retested for anything and everything.”

A New Era of Medicine

Aside from these concerns, public health in general may well benefit from the collection of such large amounts of data, which could potentially lead to new treatments or drug discovery. With over 2 million people in its database, 23andMe collaborates on research efforts with academic and industry partners, including Genetech, Janssen, MediGuard, and the Michael J. Fox Foundation.

“With approximately 85% of 23andMe customers consenting to participate in research, the company has amassed vast amounts of data, which powers research that could lead to new insights and treatments into conditions like cancer, dementia, and diabetes,” according to a 23andMe spokesperson. “23andMe has the largest cohort of genotyped and phenotyped individuals for research on the planet. Traditional research can take more than a decade and millions of dollars to conduct studies with just a few hundred participants. We can undertake real-time research initiatives drawn from our full database.”

With this surplus of data, some genome sequencing companies are looking for new ways to mine data. As an example, Veritas Genetics bought an artificial intelligence company called Curoverse in August 2017 to help start this process. Bertalan Meskó, M.D., Ph.D., who directs the Medical Futurist Institute, predicts that within the next five to ten years, genetic discoveries from these data sets will abound. “With more customers, companies will have more data. With much more data, they can use advanced algorithms, even ones of deep learning, to mine the data sets and come up with conclusions nobody has thought of before,” he says.

While much of this data will be available to for-profit companies, an ambitious initiative by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), All of Us (a part of the Precision Medicine Initiative), aims to gather large data sets to better understand how genetics relate to environment and health. Launched in 2017, the effort will use advances in “human biology, behavior, genetics, environment, data science, computation, and much more to produce new knowledge with the goal of developing more effective ways to treat disease,” according to the NIH, and will recruit a cohort of over a million diverse participants. This follows the success of the NIH’s Human Genome Project, which completed the entire sequencing of the human genome and provided the basis for today’s genetic tests.

“Now that we have a good understanding of very simple genetic disorders thanks to this remarkable project,” says Jarvik, “we’re moving into the next phase of trying to understand more complicated conditions like dementia, heart disease, and cancer, most of which [are] not caused by a single change in the genome but a series of changes, plus environment, plus chance. Large data sets are needed to study these complex interactions.”

In the meantime, for those consumers thinking of taking a genetic test, Meskó advises, “Be vigilant, don’t believe everything, and define what you look for. Even while working with a physician and a genetic counselor, it’s really complicated to get DNA changes translated into practical pieces of advice about lifestyle.”