Music produces a kind of pleasure which human nature cannot do without. —Confucius

The tango appears as no exception, in its birthplace and abroad, too.

The perception of music is a complex subject not yet fully understood that has led to a huge bibliography spreading from its physics foundations to mathematical descriptions, from a neurophysiologic basis to psychological aspects, but also setting its feet strongly on cultural facets [1]–[3]. The area, however, seems wider and more complicated than previously foreseen if we recall perceptual discrepancies, as in the case of auditory illusions, even with disagreements between right- and left-handed people, perhaps indicating variations in brain organization, as studied by Diana Deutsch [4].

How our central nervous system (CNS) decides that a given combination of sounds causes pleasure or not is a question with no definite answer yet and is not the intended subject herein.

This column only aims at showing how the tango, a tiny subset of the overall musical world, followed a path since its inception in the 1870s or 1880s that moved from rather simple consonant melodies to highly elaborated compositions rich in all sort of well-handled consonant–dissonant combinations, many cadences to give musical phrases a distinctive ending or a sense of conclusion, adequate key conversions or shifts, including rhythmic changes or even lack of rhythm.

Technology also played a significant role, having the bandoneón, a bellows-kind of musical instrument, as its unique first actor, for tango without it, to be true tango, is not conceivable.

From Consonances to Dissonances

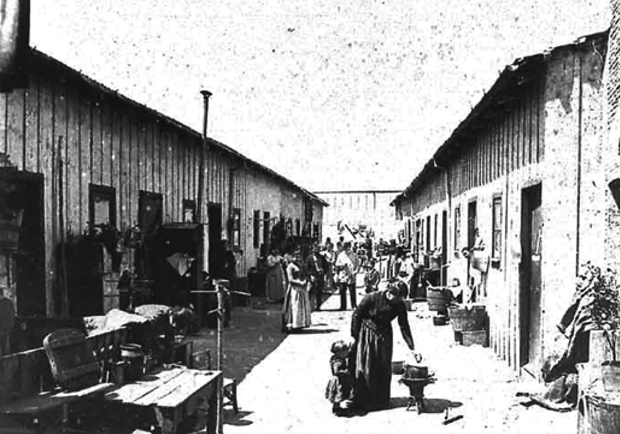

The exact origins of the tango are not totally clear, but it does go back well over 100 years, beginning as such just at the end of the 19th century. It evolved in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and in Montevideo, Uruguay, with definite influences from the African candombe [5] and the Cuban habanera, but not devoid of many ingredients typical of the strong Italian immigration that took place from roughly the 1860s until the 1930s or so. It was a rhythmic music of the city borderline neighborhoods and slums, where large tenements (conventillos) quickly developed concentrating entire families and usually offering poor sanitary conditions, with a few latrines and three or four water faucets for the entire premises (above). The instrumental groups were small (duets, trios, and quartets). The tempo was brisk and faster than today’s. The violin, guitar, and flute predominated. The bandoneón appeared later. The tango was still set in the old arrabales, where disreputable men could often be seen dancing with each other in the streets as practice before visiting a tavern or a brothel. These early tangueros enjoyed notoriety as dangerous, picaresque, and morally and sexually debased. Tangos were played and danced in brothels, most of the time by men and women devoted to non sancta activities or conditions.

The Academia Nacional del Tango (ANT) divides its evolution in ten periods of approximately 15 years each, except the first one, which spanned over 30 years [6], i.e.,

- 1850–1880 (30 years), Before Tango or The Seeds

- 1880–1895 (15 years), Prehistory or Genesis

- 1895–1910 (15 years), Hatching or Blooming or Guardia Vieja I (Old Guard)

- 1910–1925 (15 years), Formalization or Guardia Vieja II

- 1925–1940 (15 years), Transformation or Guardia Nueva I (New Guard I)

- 1940–1955 (15 years), Exaltation or Guardia Nueva II (New Guard II) or Golden Age

- 1955–1970 (15 years), Modernization and Vanguard

- 1970–1985 (15 years), Universalization or Contemporary I

- 1985–2000 (15 years), Projection or Contemporary II

- 2000–present (15 years), Sacralization.

In time, the tango would go from the brothels to the elite ballrooms of Europe and New York in the 1920s, slowly and steadily growing and spreading the world over more popular than ever before, for dancers, groups, and societies practiced it in many countries. Early full tangos historically accepted as such belong to the 1890s, that is, to the second period mentioned above. Their melodies were simple and fully consonant, as one titled Ataniche, which when its syllables are pronounced backward, it reads ¡Che, Anita!, so following a common custom in the Argentine lower social levels of those days to speak in reverse (in Spanish, to speak al vesre, meaning, al revés). Its music belongs to Ernesto Ponzio (1885–1934), who claimed Anita (Annette) used to be his sweetheart and this was an affectionate way of calling her. Written in A major, with a second part in A minor, and a nice shift to C major, it became very popular in the milongas (ballrooms) around 1900. Its chords are absolutely consonant, and the melody easily stays in the ear. But several tango historians sustain Ataniche is anonymous and that others arrogated the theme as their own until Ponzio registered it under his name. Copyrights in those days were not a common practice nor were they honored or too much respected.

Another tango of the same period, attributed also to Ponzio and perhaps composed in 1898 (that is, when he was only 13!), is titled Don Juan (Mr. John), dedicated to one prominent customer and bully or roughneck of a well-known Buenos Aires milonga. Written in A major and D major, its melodic line is also easy to memorize with absolutely no dissonance at all

A third tango example that crossed the ocean is El Choclo (The Corn or The Maize), composed in 1903 by Angel Villoldo (1861–1919) but presented publicly on 3 November 1905, at the American Restaurant (a rather fancy place) by the pianist José Luis Roncallo and his orchestra as danza criolla (creole dance) to disguise its true identity, which was shameful and socially forbidden. Many years later, in 1947, Enrique Santos Discépolo (1901–1951, one of the greatest tango authors, both as composer and poet) added beautiful lyrics to its melodic line. This tango is also fully consonant, but it already displays a significant musical evolution; it has three parts and three key shifts with perfectly handled harmonic cadences or chord series, so making its hearing quite pleasant. Villoldo named it El Choclo because for me the “choclo” is the tastiest ingredient of the “puchero” (kind of a stewpot of Spanish origin quite common in several Latin American countries that, at least in Argentina, used to be the main dish eaten by poor people). The “puchero” reference reflected Villoldo’s hope that the success of the tango would bring food to his table. To earn a living was commonly referred to as earning the “puchero,” clearly showing a social meaning.

The predominance of consonances was maintained up to the seventh (1955–1970) or even eighth periods (1970–1985), even though dissonances were timidly but increasingly incorporated while the musical richness of the tango improved significantly. Composers such as Osvaldo Pugliese (1905–1995), Aníbal Troilo (1911–1975), Marianito Mores (1918–present), and the revolutionary Astor Piazzola, and, in a way, his followers Emilio Balcarce (1918–2011) and Osvaldo Piro (1936–present), must be mentioned. Julián Plaza, pianist, bandoneonist, and composer (1928–2003), who played with the best tango orchestras of Argentina and directed the Sexteto Mayor, produced tangos and milongas with a distinct seal. Danzarín, Sensiblero, Melancólico, Nostálgico, Disonante, and Payadora are outstanding. Dissonances in them appear as a distinct feature that creates a rather attractive acoustical perception. There are others, but this column is not the place to review them. Compositions can be found and heard freely on the Internet, for example, on the Todo Tango Web site [7].

The last two periods (ninth and tenth) brought innumerable musical contributions, including the introduction of instruments not traditional in the tango environment; very timidly, however, such phenomenon had started rather earlier. All this has produced a kind of upheaval with a not-easy-to-predict future, as the old time tangueros seem to be reluctant to accept movements like the TecnoTango, NarcoTango, or ElectroTango, new approaches where electronics and the tango become entangled generating a bridge between the traditional 20th-century tango and the current 21st, while the concepts of consonance–dissonance–rhythm fuse and seem to flee, to rush out, of the usual idea held by most of the people [8], [9].

The Bandoneón

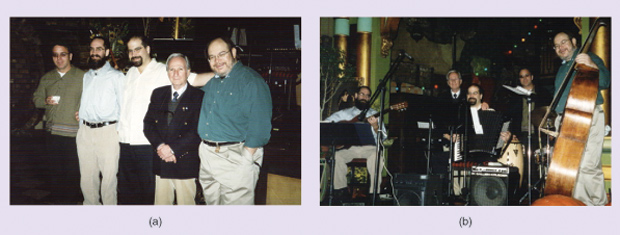

This instrument absolutely defines the Argentine tango, its true heart and soul, and it too was an immigrant to Argentina. Two German companies, Chemnitz and Heinrich Band, were sending their instruments to German musicians who had immigrated to South America. Chemnitz was known as Chemnitzer, while Heinrich Band adopted the name of bandoneón, a word that perhaps comes from a contraction of band and accordion. Among the great bandoneonistas, Juan “Pacho” Maglio (1880–1934) can be mentioned. He would go on to live from the 44 buttons to the 142 tone layout, passing through 52, 65, and 75 buttons. It was Maglio who made the first solo bandoneón recordings in 1913 [10]. The candenzas a bandoneón can produce are unique; it is even able to literally “cry” leading to emotions only comprehensible by each particular person. There were, and there are, great bandeononists certainly not possible to mention here; however, to honor him, I want to specifically give the name of Alfredo Cordisco, who turned 98 in 2014 (born on 27 July 1916), with whom I played as pianist for approximately a year when the Guardia Vieja quartet Los Ases (piano, two violins, and bass) was active back in 1951–1952 [11].

Author’s Note

This note may seem odd to bioengineers and appear out of place to other readers, but music is part of human life and the tango is part of music, and its perception is the result of several inputs complexly combined with inner feelings where the CNS and past experiences play essential roles with the added ingredient of technology, now enhanced by the electronic armamentarium, all amazing, indeed.

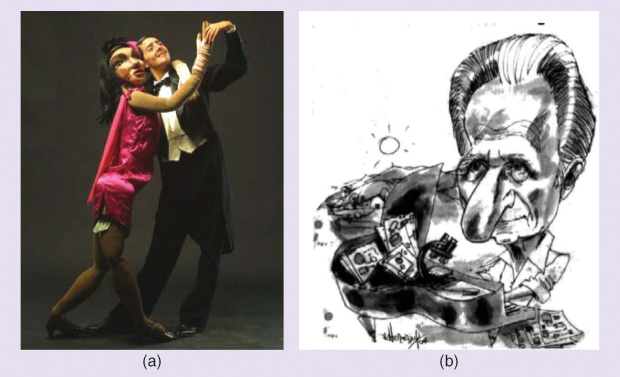

I tried to quickly run through the origins and historical development of this particular style of music, which is still new but has made an impact around the world in places as eastward as Japan or as northern as Minnesota, in the United States (above). It is strongly associated with a body manifestation, a dance—always carried out by a couple, man and woman, in close communion, even though they may be strangers—and poetry through its lyrics, where love, protest, humor, and deception are expressed, the latter adding ingredients to that perception (see “Gals Have Always Given a Bad Time to Tango Boys…“). Hence, what the brain must process and come up with in the end is the result of several different and highly complex components, i.e., melody and rhythm, body expression, and poetry (below).

[accordion title=”Gals Have Always Given a Bad Time to Tango Boys…”]

Money, power and love move the world… so many people assert… but how much better would be if love were just enough.

Here, all the suffering and hard moments many guys experienced are underlined, usually because of unloving, ungrateful gals (most often, spectacular minas who danced tango as no one else would) who did not hesitate to let them down, who knows why, at the most unexpected moment of their lives… as many tango lyrics say one way or another… and precisely, that successful first sung tango inaugurated by Carlos Gardel back in 1918, Lita (a girl’s name), later titled Mi noche triste (My sad night), tells one of these sad stories:

- Percanta que me amuraste—Gal, you (sure) let me down

- En lo mejor de mi vida—in the best of my life

- Dejándome el alma herida—leaving my soul wounded

- Y espina en el corazón—And a thorn stuck in my heart.

- Sabiendo que te quería—Knowing that I (really) loved you

- que vos eras mi alegría—that you were my joy,

- mi ternura y mi pasión—My tenderness and my passion.

- Para mi no hay más consuelo—For me there is no consolation

- Y por eso me encurdelo—and for this I am getting drunk

- Pa´ olvidarme de tu amor—To forget your (former) love.

Those first lyrics opened the road for a long list of hurt compadritos, who lost honor, manhood, courage, and even the liking of life itself; some of them easily fell into drunkardness, as that poor fellow drinking his last glass of champagne in La última copa (The last glass), rejecting the love offered by easy-going harlots:

- Eche mozo, nomás, écheme y llene—Come on waiter, and fill up all my glass

- Hasta el borde mi copa de champagne—to the very glass-top with champagne

- Que esta noche de farra y alegría—because this night of binge and joy

- El dolor que hay en mi alma quiero ahogar—The pain in my soul I want to drown

- Es la última farra de mi vida—It is the last spree of my life

- de mi vida muchachos que se va—my life, which is just going away

- Mejor dicho se ha ido tras aquella—better said it went off following her

- Que no supo mi amor nunca apreciar—who never knew how to recognize my love.

Enrique Santos Discépolo (Discepolín or Mordisquito, his nicknames; mordisquito means literally “little bite,” because of his sharp comments) was one of the great composers, both of lyrics and music. In Canción desesperada (Desperate song), written in 1945, the guy cries desperately, por tu amor, mi fe desorientada, se hundió destrozando mi corazón (for your love, my disoriented faith sunk crushing my heart… and he proceeds… cómo una mujer no entiende nunca que un hombre da todo dando su alma (how a woman never understands that a man gives everything giving his soul).

And the list could go on and on, and the reader would get tired of sticking to the same boring script and all the tango girls here and beyond would get mad at me. Thus, I had better stop here wishing and hoping that you would understand the meaning of this message, full of warm true love.

You see, girls, we give you our all, and this is what you give back—sorrow, pain, despair…However, we keep chasing you because, after all, what would the world be like without you? As the Persian poet Omar Kayham once said, “do not hurt a woman even with the petals of a rose.”

Glossary

The following few words found in the text above belong to the Argentine slang called lunfardo, mostly used in the city of Buenos Aires.

- amuraste, amurar: to abandon, forsake, desert, ditch

- compadritos, a guy who brags, boasts

- encurdelo, to get drunk

- farra, spree, big party

- minas, woman, an attractive woman

- percanta, woman, loving woman.

[/accordion]

Dancing deserves a separate paragraph, as dancing tango with someone for the first time involves a great deal of uncertainty [12]. At first, new dance partners watch their feet nervously, unsure of where to step. But with time, rhythm and flow can develop between them. Eventually, it might seem as though they have known one another for years and can predict their partner’s moves. Suzanne Dikker, a cognitive neuroscientist, aims at unravel the complicated neuroscience behind such interpersonal chemistry, perhaps looking for some kind of survival which is dependent on how we synchronize with each other. Dikker hooked up two pairs of tango dancers with EEG headsets to measure each person’s brainwaves. She then performed three experiments:

First the previously acquainted pairs danced to a song like they normally would. Then they switched partners to dance with someone they were less familiar with. After that the dancers stood in place with their initial partners and imagined they were dancing. All the while, Dikker projected graphics and numerical scores onto the walls of the room, depicting when the dancers’ brains were in synchronism, and when they were less so. Dikker is using the tango to study brain synchrony for a couple of reasons. For one, she finds the interactions between two tango dancers fascinating because of the amount of coordination it takes to make complicated movements look natural and instinctive. The tango is interesting and complex to study because depending on whether you are a leader or a follower, there are different brain states involved in anticipating what your partner will do [13].

Conclusions

Besides its anecdotic taste, full of memories for the older and possibly quite attractive to the younger, we find in the tango a wealth of material that tells the bioengineer, look, hear … here you have at hand another area where your ingenuity can be challenged, perhaps delving into the nervous system by means of brain records and adequate software, perhaps with a bandoneón electronic version, or why not, as an efficient therapeutic procedure.

References

- M. E. Valentinuzzi and N. E. Arias, “Human psychophysiological perception of musical scales and nontraditional music,” IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag., vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 54–60, Mar.-Apr. 1999.

- M. E. Valentinuzzi, D. González, and G. Palloti, “The perception of musical consonance,” Trans. University College of Environmental Sciences (Radom, Poland), vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 5–22, Mar. 2009.

- D. L. Gonzalez, G. Pallotti, and M. E. Valentinuzzi, “Pitch perception and cochlear biomechanics,” in Proc. 17th Int. Conf. Mechanics in Medicine and Biology (ICMMB-17), Kraków, Poland, 19–24 Sept. 2010.

- D. Deutsch. [Online].

- J.C. Caceres, Tango Negro (in French). Paris, France: Editions du Jasmin, 2013.

- Academia Nacional del Tango (Argentine National Academy of Tango). [Online].

- Todo Tango (All Tango). [Online].

- El Ortiba. [Online].

- [Online]. Available: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LrZs30Z1ZAk

- E. Rivadeneira. Tango of mine, Todo Tango. [Online].

- D. Pedercini. Talking with Alfredo Cordisco. [Online].

- M. E. Valentinuzzi, “Dancing the Argentine Tango: A three-minute love affair,” Bull. Tango Soc. Minnesota, vol. 3, no. 3, July–Sept. 2001.

- E. Chen. (2014, Mar. 28). Ballroom brainwaves: A neuroscientist studies the brains of tango dancers in an attempt to understand interpersonal connectedness. Scientist. [Online].