Humankind today is facing an array of challenges—global climate change, the depletion of natural resources, water scarcity, and an aging population, just to name a few. It is more important now than ever for us to address these issues and find solutions to how we and future generations can continue living on this one earth. Business entities, with their influence in society as well as resources far beyond the individual, have great potential to make a difference. We cannot necessarily expect, however, that businesses will relinquish profits for the sake of sustainability and social betterment. What is needed is an innovative form of business in which pursuing sustainability is tied to enhancing corporate value. The approach that Mitsubishi Chemical Holdings Company (MCHC) is taking to realize this is embodied in the concept of “KAITEKI“ [1].

MCHC, which is the largest chemical conglomerate in Japan, is promoting KAITEKI as a value to be shared by all companies in the 21st century [2]. Originally meaning “pleasant” or “comfort” in Japanese, MCHC chose KAITEKI as the name of an overarching concept that stands for a truly sustainable state of health and well-being, not just for individuals but for society and the earth as a whole.

The KAITEKI Institute (TKI) was established in April 2009 by MCHC. TKI functions as both a think tank and research institute, taking a long-term perspective of 20–50 years to work on some of the most important themes for the future of human society. As a researcher at TKI, I am part of a team working on health care, and my specific area is aging. In the following sections, I will discuss some of my research and a modeling study of the aging population in Japan and the United States—data that have bearing on the type of health management systems biomedical engineers will be developing in the future to keep the elderly independent and mobile for longer.

The Aging Society and Long-Term Health Care Trends

In Japan, the percentage of the population over the age of 65 was 25.1% in 2013 and is forecast to increase to 33.4% in 2035. It is the country with the fastest rate of aging population in the world and has been for the last 50 years. Japan is at the frontier of the issue of an aging society, which many countries will also be facing in the imminent future, so what happens here is being closely watched around the world.

A major challenge is the management of health. This is a high-priority issue for people of all ages, but especially for the elderly. According to a survey by the Japanese government [3], the top causes of worry and anxiety for elderly people were: health management (78% of respondents), nursing care (58%), and income (39%). The National Livelihood Survey (2010) found that the top five reasons that elderly people became bedridden and required nursing care were: cerebral stroke (21.5%), dementia (15.3%), fragility due to old age (13.7%), joint conditions (10.9%), and bone fracture or injury from fall accidents (10.2%). Needless to say, preventing these conditions is important not just for mitigating diseases that lead to death but for the everyday well-being of elderly individuals.

For society as a whole, the increasing number of elderly people poses issues in many areas, not least of which is the social welfare system. In Japan, there are three main systems for social welfare. One is the medical insurance system, which is intended to be universal and cover all citizens. Another is the elderly care insurance system, which only a few countries in the world have implemented so far. Last is the pension system, which insures life after retirement. It is a simple fact that if the aging population of a country increases, so does the cost for these kinds of programs, putting pressure on national budgets. Japan is a clear example; in 1970, social welfare costs accounted for 5.8% of national income, but by 2008, it had swelled to 24.9%. According to a report [4] by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan, the total social welfare costs were approximately 90 trillion yen in 2006; forecasts for the year 2025 show the total will reach a staggering 141 trillion yen. There is no denying that social welfare at this level is totally unsustainable. Even if “Abenomics”—the optimistic economic policies advocated by Prime Minister Shino Abe—goes according to the best possible scenario and Japan achieves 2% economic growth per year, it will not be enough to sustain the social welfare system in the direction it is currently headed.

Annual government revenue is largely influenced by the size of the working population. If we were to define this as the population under the age of 65, Japan is expected to lose 37% of its working population during 2010–2050 [5]. This is the largest drop in working population for this period of any country in the world. Unless something revolutionary occurs to cause an incredible boost in productivity in the near future, dwindling economic output is unavoidable for Japan. With increasing annual expenditures and decreasing revenue a certainty in Japan’s future, it is easy to see that budgets for medical and nursing care and pensions will be cut drastically. As the demography continues to change at a rapid pace, Japan is in urgent need of a plan to deal with this future situation.

As mentioned before, many countries are quickly following in Japan’s footsteps, mostly countries in Asia, such as Singapore, South Korea, and China. Developing countries are also going to start to age in the future, too; by 2025, it is forecast that there will be 1.5 billion people over the age of 65 on this planet. Statistically, this would mean that every 3.5 persons of working age will have to support one elderly person [6]. Aging is not a problem particular to Japan. It is a challenge for the whole world.

Modeling Study of Changes in Degree of Independence with Progressing Age

The above seems to paint a dark picture of an aging society, but seen in the wider context of human history, longevity for so many people could be considered a great achievement of human civilization. In the past, people viewed human life stages as childhood, adulthood, and “old,” but now, this last stage of “old” is so long that it is often divided further into “old,” and “oldest old,” the latter being around 75 years old and above. For the first time in history, there are many people in the “oldest old” category, and this population continues to grow. These very old people can be considered the“new humans,” recent newcomers in the history of mankind.

Under these circumstances, there has been much development in the study of the biological processes of aging, including mechanisms of dementia and other diseases. However, there have not been many studies looking into the day-to-day lives and attitudes of the oldest old living in society (as opposed to nursing homes and other institutional environments), even in Japan. Getting a perspective into the experiences of the oldest old and their unique needs is critical for establishing social systems and businesses and for the realization of a KAITEKI society. Recognizing this situation, TKI has been conducting research from various angles to gain insights into the lives of the oldest old.

One of our recent efforts in this field was a modeling study of patterns of change in people’s level of independence as they age. Conducted in 2012, this was a joint study with Prof. Hiroko Akiyama of the Institute of Gerontology, the University of Tokyo, who is known for her work with the Japanese Study of Assets and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (JAHEAD) [7]. Her analysis of JAHEAD data that identified patterns of aging for Japanese men and women has drawn especially widespread attention since being presented in 2009 [8]. While there have been numerous epidemiological and medical studies on dementia and chronic diseases of the elderly, Prof. Akiyama’s work is unique for its broad view of the changes in conditions of people living in normal noninstitutional settings.

The objective of our joint study with Prof. Akiyama was to see what can be learned by comparing patterns of aging for people in Japan and the United States. The research questions for our study were as follows:

- What are the long-term trajectories of functional health for older men and women?

- Do health trajectories differ by biosociocultural context (sex, race, and country)?

- What are the factors that affect independent living?

The methodology and findings of the study are discussed below.

First of all, to provide a background on the sources of data, JAHEAD is a large-scale longitudinal panel survey that is still ongoing today, which started in 1986 as the Japanese version of an American study, the Study of Assets and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD) by Michigan State University. JAHEAD looks at almost 6,000 Japanese subjects over 60 years old, randomly sampled from the census register. Surveys are administered every three years, with extensive questions covering social relationships (family/friends/neighborhood), health status (subjective health measures/functional health, i.e., physical and mental health/presence of diseases and impairments), and daily habits. Our current study used data from the approximately 20-year period from 1987 to 2006. Our data on Americans came from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) [9], also an ongoing, large-scale longitudinal panel survey. HRS administers surveys to a sample of approximately 27,000 Americans over the age of 50, every two years. Launched in 1992, HRS has since merged with Michigan State University’s AHEAD study mentioned previously, making the method and content of HRS similar to that of JAHEAD, which was suitable for our study. The HRS data we used are from 1992 to 2010.

In previous research, Prof. Akiyama had developed a system of scoring people’s level of independence—the “independence variable”—that is based on several question items selected from the JAHEAD survey. For our present analysis, we recreated a similar system, selecting five items contained in both the JAHEAD and HRS, which we assessed as most indicative of subjects’ ability to live independently. Three items regard activities of daily living (ADL) [10]: bathing or showering, climbing one flight of stairs without resting, and walking several blocks. The remaining two items regard instrumental ADL (IADL) [11]: making phone calls and shopping for groceries. Depending on subjects’ responses on whether they were capable of doing these activities, they were given an independence variable score on a scale of 0–3. The meaning of each score is as follows:

- 3: “fully independent,” capable of ADL and IADL

- 2: “ADL independent,” capable of all three ADL but requires assistance with one or more IADL

- 1: “not independent,” requires assistance with one or more ADL

- 0: death.

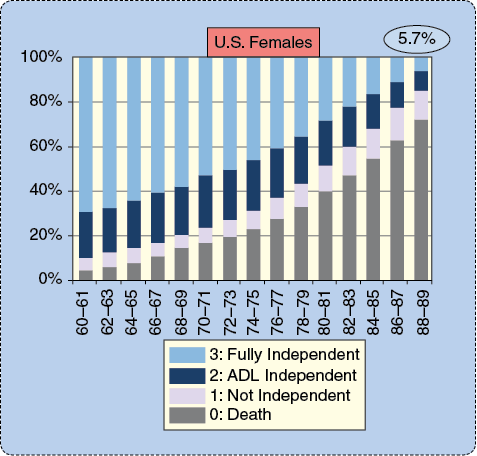

Data on American and Japanese people were analyzed using the scoring system to obtain the frequency distribution of each independence variable by age. Figure 1 shows the results for Caucasian females in the United States (the HRS surveys various racial groups, but we chose Caucasians for the purpose of our study). The vertical axis shows the percentage of subjects for each independence variable, and the horizontal axis shows age. Naturally, the percentage of deaths, or variable 0, rises as age advances. On the other hand, even at age 88–89, there are 5.7% of subjects with a score of 3, who are fully independent. For Caucasian men, this percentage was 5.5%, Japanese men 6.9%, and Japanese women 11.1%. This establishes that while level of independence declines for the majority of people, a portion of the population is able to maintain functions for independent living well into old age, and the proportion differs across gender and country.

Next, we looked at changes in functional health over time for individuals. In a previous analysis, Prof. Akiyama identified patterns of aging for Japanese men and women using “latent class analysis.” This is still a relatively new technique that aims to identify unobservable groups or subtypes—or “latent classes”—in big data. It is thought to be capable of overcoming imperfections in data, such as inclusion of deficient or defective information—and is used in applications such as analyzing consumer behavior in the field of economics. The analysis basically can presume averages for variables, by which typical patterns are revealed.

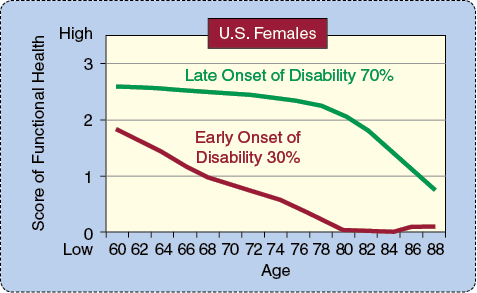

Prof. Akiyama’s previous analysis of JAHEAD data identified two main patterns of aging for Japanese people: “late onset of disability” and “early onset of disability.” The “late-onset” pattern shows decline in functions necessary for independent living, indicated by a lower independence variable score, starting in the late 70s. The “early-onset” pattern shows this decline starting in the 60s. Our latent class analysis of HRS data for Americans also revealed these two patterns. Figure 2 is the result for American females; 70% of subjects were found to be of the late-onset type, and the remaining 30% were of the “early-onset” type. Results for American males showed 66% late onset and 34% early onset. Analysis of Japanese data in our study showed very similar results to Prof. Akiyama’s previous analysis: Japanese females were 92% late onset, 8% early onset; Japanese males were 77% late onset, 12% early onset. What stands out as a distinct characteristic of this last group, Japanese males, is that 10% deviate from either of the patterns and show what can be called a “successful aging” pattern, with full functions for independence maintained at age 80 and above. The fact that this apparently ideal pattern of aging existed in the set of Japanese males, but not Americans, is a point that merits further study. However, we must note that there are differences in lifestyle and culture between the two countries that may be reflected in the responses to the survey questions (for instance, driving is indispensable for daily activities in the United States, whereas people in Japan are more likely to walk), so a straightforward comparison of Americans and Japanese would be too simplistic. One thing that is certain, however, is that the great majority of people in both the United States and Japan are of the late onset of disability pattern, who gradually start to lose functions for independent living from the mid-70s and onward.

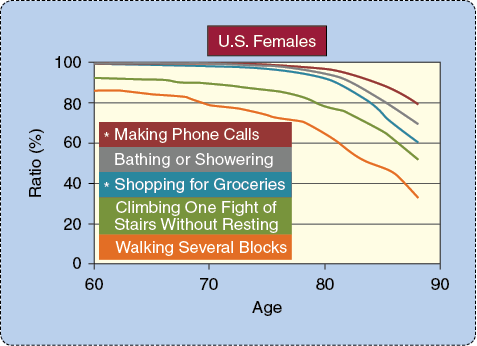

For each pattern of aging in both the American and Japanese sets, we conducted a detailed analysis to determine which ADL or IADL of the independence variable most contributed to the decline in independence. For this discussion, we will focus on the analysis for the “late-onset” type to which the majority of both Americans and Japanese belonged. Figure 3 shows the results for American females. The vertical axis is the percentage of subjects who were able to do each activity, and the horizontal axis is age. The graph shows that the activity for which the rate of decline is most severe is “walking several blocks,” followed by “climbing one flight of stairs without resting.” Analysis for American males and for Japanese males and females showed the same order, establishing that these two activities that demonstrate mobility functions decline the most rapidly and from the earliest age. This indicates that maintenance of mobility function is the most critical factor for people to live independently into old age.

The Future May Lie in Enhancnig Mobility and Motivation

Currently, many universities and corporations are working to develop various technologies to support the lowered mobility functions of elderly people, for instance, skeletal structure robot suits that elderly people can wear to move around, or personal mobility devices that are small, agile, and easy to drive. We at TKI have high hopes for the actualization of these technologies.

On the other hand, in our vision for a KAITEKI society, we think that it is most important to have systems of health promotion for elderly people to actually prevent the decline in mobility function. Because health conditions of the elderly are so diverse, programs will need to be highly tailored for each individual. To do this, we will need a way for people to see and keep track of their health and to engage in appropriate health-promoting activities such as exercise, eating right, and getting adequate sleep. Furthermore, many studies on people of working age have established the importance of motivation for people to continue health-promoting activities. As many of us may know also by first-hand experience, motivation is difficult to induce and even more difficult to maintain. To do so for elderly people, who have even more diverse needs than younger people, will be an especially big challenge.

TKI is currently working on developing health management systems to prevent fall accidents in elderly people, which is the top cause leading to loss of mobility functions. The system we envision uses an innovative device to visualize individuals’ risks for falling and their mobile capabilities, and exercise programs will be formulated based on this information. Gamification of the exercise will make it enjoyable and provide motivation to continue. Feedback on mobility functions from periodic evaluations will let people clearly see their progress and provide further motivation. In the future, we plan to look further into how such health promoting systems can be adopted and utilized by social systems. We also have plans to conduct further studies on motivation to understand the psychological aspects for elderly people to start and continue exercise.

In the KAITEKI society that TKI envisions, individuals will actively manage their own health and be able to maximize their healthy years of physical independence. People will lead active and fulfilling lives into old age, continuing to work and participate in society. When this is realized 20–30 years from now, it will be a world in which people will embrace and celebrate the joys of old age.

References

- Y. Kobayashi, Good Chemistry for KAITEKI: A Challenge to a Sustainable, Healthy and Comfortable Society. Tokyo, Japan: The KAITEKI Institute, Inc., 2011.

- Y. Kobayashi, The Management Codependent on Mother Earth; The MOS Manifesto. Japan: Nikkei Publishing, 2013.

- 2009 Survey on elderly people’s attitude towards daily living. (2009). [Online].

- National Council for Social Security, 2008 Final Report.

- K. Ward, The World in 2050. The Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation, Ltd. Jan. 2012.

- National Institute on Aging, NIH. NIH Publication no. 11-7737. Global Health and Aging. [Online].

- [Online]. Available: http://www2.tmig.or.jp/jahead/

- H. Akiyama, “Adaptation in the oldest old: The role of mastery beliefs and social relations for life satisfaction,” in Proc. 61st Annual Scientific Meeting of Gerontological Society of America, 2009.

- The University of Michigan Health and Retirement Study (HRS). [Online]. Sponsored by the National Institute of Aging.

- S. Katz, T. D. Downs, H. R. Cash, and R. C. Grotz, “Progress in development of the index of ADL,” Gerontologist, vol. 10, pp. 20–30, 1970.

- M. P. Lawton and E. M. Brody, “Assessment of older people: Self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living,” Gerontologist, vol. 9, pp. 179–186, 1969.