Mounting evidence suggests that psychedelics may be useful for treating a range of different neuropsychiatric conditions that currently have limited treatment options. On May 4–6, 2021, leaders from academia and industry discussed a variety of issues related to the development and adoption of psychedelic drugs for different conditions during the virtual Psychedelic Therapeutics and Drug Development Conference. Selected topics from the conference are presented below.

Psychedelic-assisted therapy for cancer patients

For people with cancer, the prevalence of psychiatric disorders including major depression and anxiety is as high as 30%–40%, and up to 25% of patients with advanced cancer exhibit existential distress. Currently available pharmacological and psychosocial treatments offered to cancer patients have limited effectiveness, but preliminary studies by Stephen Ross, M.D., associate director of New York University’s Langone Health Center for Psychedelic Medicine, and others suggest that psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy may offer an effective new treatment option for these patients.

In a 2016 double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 29 patients, Ross and colleagues found that a single dose of psilocybin used in conjunction with psychotherapy successfully reduced symptoms of anxiety and depression in patients with cancer-related psychological distress [1]. A recently published follow-up study found that the effects persisted four and a half years later in participants who were still alive [2].

“In phase two studies we found that psilocybin can be safely administered, that it’s a rapidly acting anti-anxiolytic agent and antidepressant [with] highly significant clinical outcomes,” said Ross. “What’s next is there should be phase IIb/IIIc multi-center trials in this area that look at anywhere from terminal cancer to early diagnosis to chronic forms of cancer.” Ross stressed the importance of replicating his group’s findings. “We need bigger trials, we need to optimize the design,” he said. “And we need to interrogate potential mechanisms of action.”

If future trials determine that psilocybin is an appropriate treatment, the next hurdle will be ensuring access. “The goal is how can you get this to as many patients as possible if it works and, working at Bellevue Hospital, my main goal is to get it to those who are poor and indigent who typically don’t get a chance to benefit from novel therapeutics,” said Ross.

Part of the overall reticence to trying new pharmaceuticals to treat psychological distress in cancer patients has been due to possible interactions between these drugs and oncology medications. But that calculus may be changing. “We’ve got other therapies coming in, we’ve got things like immunotherapy,” said Malcolm Barrett-Johnson, M.D., chief medical officer of the London-based psychedelic company Albert Labs. “These have got a much better safety profile, generally speaking, so now is the time to actually go back and address the other issues in patients suffering.”

Instead of conducting randomized-control trials, Albert Labs is using real-world evidence (RWE), which relies on observational data collected outside of clinical trials, to evaluate the efficacy of psilocybin-assisted therapy for cancer patients. “With real world evidence what you’re doing is effectively looking at patients in the setting in which they’re being treated normally,” said Barratt-Johnson. “It allows a lot more flexibility and also allows you to put patients into a trial setting far more rapidly and at a decreased cost.” He noted that RWE also allows evidence and safety data to be collected from a larger, more heterogeneous group of patients than most randomized control trials.

Albert Labs hopes to begin collecting data from cancer patients treated with psilocybin by the end of the year and to publish interim results after three to four months.

Personalized DMT-assisted treatment for addiction

Entheon Biomedical is a biotech company developing personalized N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT)-assisted treatments for addiction. “Approximately 21.2 million Americans suffer from some form of substance use disorder, and approximately only one in 10 of those people receive any form of adequate treatment,” said Timothy Ko, CEO of Entheon. “The root of these problems is thought to be psychological and emotional in nature, rather than purely habitual, and so the solutions must be targeted at the psychological and emotional levels.”

DMT has been used for centuries in traditional medicine in the form of ayahuasca and is naturally occurring in the human body. DMT elicits vivid visual imagery, powerful emotions, and “a deep clarity and insight into one’s life and relationships, ultimately resulting in dismantling of deeply held beliefs,” said Ko. Entheon focuses on DMT rather than other psychedelics because it can be precisely administered and is short-acting, allowing practitioners to end treatment quickly if a patient experiences an adverse reaction.

Entheon’s proposed treatment protocol has three stages. The first stage involves EEG, genetic, and metabolic analysis to predict how a particular patient is likely to respond to DMT and to customize treatment. To assist with this, Entheon recently acquired HaluGen Life Sciences, which has developed and commercialized a prescreening test for genetic markers that predict a person’s reaction to hallucinogenic drugs and potential side effects. The second stage of Entheon’s treatment is a 60–90-minute physician-assisted intravenous administration of DMT, facilitating a mind-altering experience under EEG monitoring. The third stage is integration, providing psychotherapeutic support that strengthens new perspectives, belief systems, and behaviors following psychedelic treatment.

Entheon plans to begin a proof of concept trial in the Netherlands at the end of 2021 and has proposed pilot studies for nicotine, alcohol, and opiate addiction in 2022–2023.

Integrating technology with psychedelic-assisted therapy

Albert Rizzo, Ph.D., director of the Medical Virtual Reality Lab at the University of Southern California, talked about the potential of combining psychedelic-assisted therapy with virtual reality (VR) therapy, which is already being used to treat a variety of mental health conditions, including phobias and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He noted that while there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that both approaches are effective, that doesn’t necessarily mean that there will be additive value in combining them.

“I think we need to say when VR may be appropriate for crafting an experience and when it’s not going to be appropriate, and how to customize it to the needs and the therapy goals of your patient or client,” said Rizzo. “Our model proposes that strategic moves at critical junctures may be useful.” For example, he suggested that a calming VR session may be useful for an anxious patient at the beginning of a psychedelic-assisted therapy appointment.

Rizzo highlighted five core elements of VR that could be customized for psychedelic-assisted therapy, each existing on a continuum: activity level (more physically active to more passive), content (more realistic to more surrealistic), sensory predominance (mostly visual to multisensory, possibly including sound, olfaction, touch), interpersonal engagement (more socially oriented to more private), and psychic activation (more activating to more calming). He noted that VR with virtual patients could also be used to train therapists to administer psychedelic therapy.

Besides training therapists and augmenting psychedelic-assisted therapeutic sessions, technological tools might be able to serve both patients and practitioners after a session where a psychedelic was administered. “A lot of therapists are speaking about this time period after the psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy and before the patient is able to come back into the office and that they have this black box of care that they don’t like,” said Kelsey Ramsden, CEO of MINDCURE. As a solution for this, MINDCURE has developed an app called iSTRYM, which is designed to assist both practitioners of psychedelic-assisted therapy and their patients.

For patients, an AI-driven data analysis tool monitors how they are doing after a psychedelic-assisted therapy session and helps them select protocols that could be helpful such as breathing exercises or meditation. For practitioners, iSTRYM contains a database of existing protocols used in psychedelic-assisted therapy. “It’s almost like the Netflix of psychedelic therapy,” said Ramsden. Clinicians can also track how their patients are doing between sessions. “They have a dashboard that allows them to witness all of the people that are in their care,” said Ramsden. “People who are maybe not doing as well get bumped to the top of the list, and they’re able to reach out to them and offer them assistance,” said Ramsden.

Developing new psychedelics

Another prominent topic in the conference was the development of new psychedelic compounds.

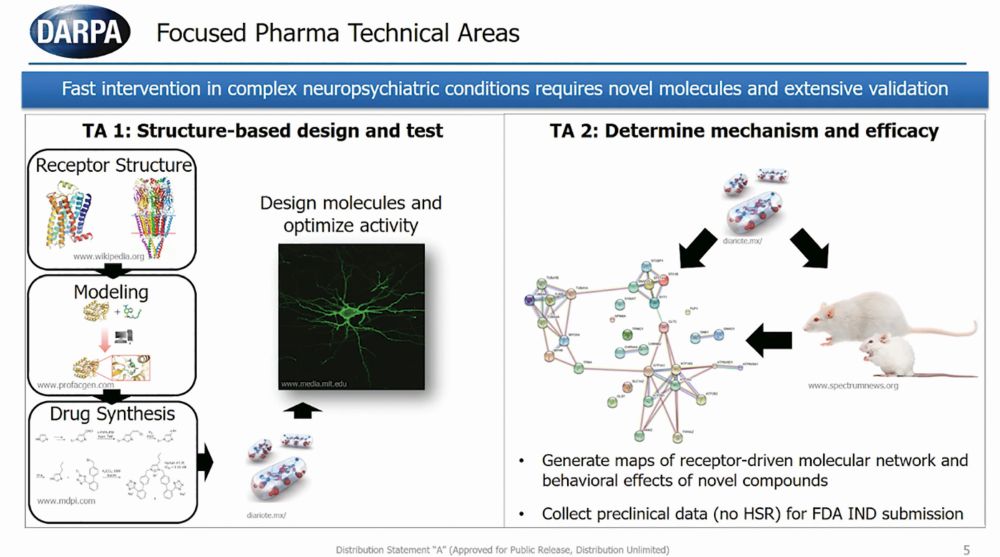

Tristan McClure-Begley, Ph.D., program manager of Focused Pharma at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), talked about the dire need for novel mental health treatments for people in the military and veterans, highlighting that roughly 20 veterans die by suicide every day. “As in many indications and many conditions the military represents a magnified view of the impact on society,” said McClure-Begley.

The Focused Pharma program funds the structure-based design of novel psychedelic compounds, the study of the behavioral effects of these novel compounds, and the collection of preclinical data on their efficacy (Figure 1). The ultimate goal is to have the FDA approve a first-in-class drug that has rapid and long-lasting effects on alleviating neuropsychiatric symptoms without eliciting hallucinations or delusions.

“The fact is we have a very diverse population with very diverse ideologies and very diverse physiologies underlying both the nature of their mental illness and the nature of its treatment,” said McClure-Begley. “In order for us to maximize the percentage of the population that can benefit from psychopharmacological intervention, we need to amplify the size and the diversity of our psychopharm field.”

One reason why new compounds are needed is that existing psychedelics have complicated pharmacology that can result in side effects such as valvular heart disease and adverse psychological effects.

“If we can understand how they interact with their targets we could potentially design or discover medications that can rescue individuals from untoward experiences,” said Bryan Roth, M.D., Ph.D., professor of pharmacology at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. “It’s also possible that this understanding could allow for the development of combination therapies to improve the efficacy and limit the side effects of psychedelic medications.” Roth and his lab study the molecular details of how psychedelic drugs interact with receptors in order to use this info to develop new psychedelic and nonpsychedelic neuropsychiatric medications.

Roth is collaborating with the biotechnology company Bright Minds to develop psychedelic compounds that target specific serotonin receptors (5-HT2C and 5-HT2A). Revati Shreeniwas, M.D., chief medical officer of Bright Minds, cited a recently published phase 2 trial that found that psilocybin and the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor escitalopram had similar efficacy in treating depression as evidence for the need for new drug development [3]. “The trial did have some trends towards positive effects in the secondary endpoints for sure, but it certainly does tell us that there is room for improvement,” said Shreeniwas. “There’s room for targeting the patients better and for using better and more selective compounds to treat this disorder.” Bright Minds has compounds for a variety of disorders including opioid use disorder, binge-eating disorder, Alzheimer’s, depression, and PTSD in early and late preclinical trials.

Policy considerations

Rick Doblin, Ph.D., founder and executive director of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS), discussed the results of a new multisite phase 3 clinical trial that found that MDMA-assisted therapy successfully treated symptoms of severe PTSD [4].

“The fact that we found no site-to-site variability means that the training program works; we can scale this,” said Doblin. He said the next step will involve answering implementation questions such as how the drug will be rescheduled by the Drug Enforcement Administration, whether insurers will cover psychedelics, and whether the FDA will require a patient registry or impose a lifetime cap in the number of times a person can receive MDMA-assisted therapy.

Ismail Ali, J.D., policy and advocacy counsel for MAPS, discussed the importance of ensuring equitable access to psychedelic care. He highlighted the importance of ensuring that a diverse group of practitioners are trained to deliver psychedelic-assisted therapy and asserted that culturally competent care is an essential requirement for training therapists [5]. Also vital, said Ali, is ensuring that psychedelic-assisted therapy is financially accessible and not limited to people with certain forms of health insurance.

“If you drop a new intervention into an unjust system, we actually risk increasing the disparities of health,” he said. “If people who are entering the space are not thinking about actively reducing that gap—ideally eliminating that gap—then even the most well-intentioned efforts will inevitably contribute to those disparities,” he said.

Future of psychedelics

Two main themes emerged from the conference: Psychedelics are on the verge of becoming more widely known and accepted for their therapeutic potential. But at the same time, it will take a lot of work to develop new drugs, prove their efficacy, and integrate psychedelics into health care.

“There are a huge number of hurdles still, a lot of money needs to be raised, a lot of regulators need to frame things so that this revolution can take place at scale,” said Henri Sant-Cassia, founding partner of the Conscious Fund, which invests in early-stage ventures in psychedelic medicine. “There will be lots of failures, there will be lots of trial and error and a lot of heartache. But, if everything aligns properly, I think it is inevitable that over time, psychedelic medicine—certainly some elements—of it will become firmly embedded in the mainstream.”

References

- S. Ross et al., “Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial,” J. Psychopharmacol., vol. 30, no. 12, pp. 1165–1180, 2016.

- S. Ross et al., “Acute and sustained reductions in loss of meaning and suicidal ideation following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in life-threatening cancer,” ACS Pharmacol. Translational Sci., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 553–562, 2021.

- R. Carhart-Harris et al., “Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression,” New Engl. J. Med., vol. 384, no. 15, pp. 1402–1411, 2021.

- J. M. Mitchell et al., “MDMA-assisted therapy for severe PTSD: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study,” Nature Med., 2021.

- M. T. Williams, S. Reed, and R. Aggarwal, “Culturally informed research design issues in a study for MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder,” J. Psychedelic Studies, vol. 4,

no. 1, pp. 40–50, 2019.