In April 2016, in honor of Autism Acceptance Month, Apple released a video that quickly went viral, racking up more than 4 million views in its first few days. It shows a teenage boy named Dillan whose life has been completely transformed by the use of an iPad. As a nonverbal person, until he learned to use the device, he had no way of showing people that he was aware, thoughtful, paying attention, and eager to communicate. He just didn’t have the necessary control over his body’s vocal apparatus to let people know he was really there. Suddenly, this little piece of 21st-century technology gave him that ability. For him, the technology has been literally life-changing.

For several years now—especially since the introduction of the iPad and the subsequent explosion of tablets and specialized apps for communication and other skills—electronic devices, which for most people function as just entertainment or convenience, have had profound and transformative effects on the lives of people on the autism spectrum. For Dillan and many others like him, it has meant the difference between almost utter isolation and an inability to communicate and a life of interaction, learning, and expressiveness. “So many people can’t understand I have a mind,” Dillan says in the video. “All they see is a person who is not in control.” In an e-mail interview with the online tech site Mashable, he said that when he’s at school, “I now can have a conversation.” He says that he can share answers to questions with his classmates and “amaze them that this totally awkward and sometimes strange guy is as smart as they are.”

Apps to assist with communication for those who have limitations of speech due to autism-spectrum conditions or other special needs span a wide gamut, and they continue to improve rapidly. Some are designed to help young children or those who lack reading and writing skills to communicate basic needs or requests. They use basic picture tiles the nonreading user can rearrange to express simple sentences, which the device speaks aloud. For others, who can read and write but are unable to speak or have a conversation, being able to type out sentences that reread aloud in a user-selectable voice makes it possible to have very natural real-time conversations with friends, family, and teachers. The potential for improvement in the lives of people across the spectrum of autism disorders continues to expand. New tools are helping enhance the lives of those who have mastered the basics of communication and interaction and hope to develop further skills in schools, the workplace, and in social relationships.

Social Stories

Gregory Abowd (Figure 1, right), a distinguished professor in the School of Interactive Computing at the Georgia Institute of Technology, where he directs the Autism and Computing group, has a particularly strong and personal motivation to pursue his work on systems to help autistic individuals build their skills for interacting with people and the routine daily interactions of life: he has been doing such research since 2002, spurred by the incentive of helping his own two sons, both of whom have autism. “I saw the transformation of my oldest son,” Abowd says, “from when he was, for the most part, an outwardly normally developing child of 18 months to within eight months when he was very clearly a different child.” That started Abowd on the path to applying his work on ubiquitous computing to developing systems for both diagnosing and aiding the social development of children with autism.

Abowd has developed a variety of projects that apply his computational expertise in this area: “I’ve worked on technology to help the individual, but I’m also interested in diagnosis, in ways to try to support intervention, to support objective measures of behavior for researchers, and ways to try to use social media as a means to provide near-real-time social support for adolescents.” For example, one research project, developed into a commercial product by a company called Behavioral Imaging Solutions, is a diagnostic system that allows parents to carry out an initial screening for autism without even leaving home. “The basic idea is there’s an app that parents can download onto their phone,” Abowd explains, “and they record four different well-defined interaction scenarios with their child, then upload that to a service, and then a diagnostician views those videos and tags them with evidence or lack of evidence of certain behaviors, and uses that to inform a diagnosis of autism according to the most recent DSM-5 criteria.”

Other research projects from his lab have shown promising results but have not yet been developed as products. One is a variation on a standard technique used in teaching young people with autism how to prepare for interactions with people and situations that are new to them or that they have anxieties about. A standard technique called social stories has parents or teachers construct a story about a particular interaction, such as going to a movie or a restaurant, to prepare the child for the experience. Abowd’s interest was in how to introduce decision making into the story. If the story concerns standing in line to buy a movie ticket, but it turns out the desired movie is sold out, what then? “Social stories don’t really address that kind of in-the- moment decision making, but it turns out to be a really important skill for individuals to try to develop,” he says.

To address that, Abowd and his team turned to the wisdom of the crowd. Using a system of online crowd-sourced assistance developed by Amazon called the Mechanical Turk, Abowd’s group was able to get thousands of responses from people about the different choices and challenges that could come up in a given scenario and how they might be addressed. The many suggestions were distilled to create a set of menu choices parents could select from to create their own individualized storyline and choice points, which they could then run through with their child. “There’s a huge number of social situations and a huge number of things that can go wrong, and a large variety of ways one can go about repairing a social situation,” Abowd says. Because it’s difficult for an individual parent or a teacher to have to think of all these possibilities to build into a story, Abowd believes that this crowd-sourced approach shows great promise.

Another variation of harnessing the wisdom of the crowd can be used for real-time assistance. “A lot of people in the autistic community go to online forums, and they ask questions in the hope that people who are like them will give them useful advice and will be empathetic and sympathize with them,” he says. “This is true, but the problem is you don’t get answers all that quickly. You may wait a day or several days.”

Again, crowd-sourcing might be able to help, Abowd found. “One of the advantages of the crowd is they can be very fast in giving answers. If you took a question someone posted on an online forum for Asperger’s, and you posted it to the crowd, you can get answers in minutes. The real challenge is, how do those answers compare to the answers from people on the forum? So we did a systematic study of this, and surprisingly found not only are the answers you’re getting more succinct and informationally valid, they are just as good from an empathy perspective. They were addressing people’s emotions as well, which I found fairly surprising.” Though the experimental results were promising, the system has not yet been developed into an app that autistic people can use.

Conversation Simulators

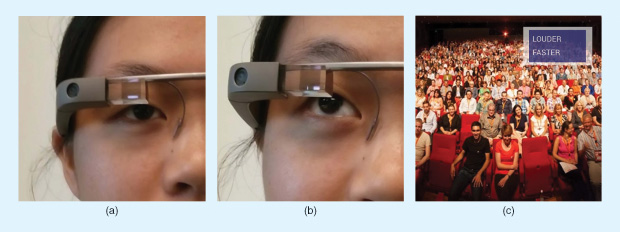

Meanwhile, researchers are developing tools aimed at those who are already on the higher-functioning end of the spectrum that could help promote communicative skills and the ability to function in the unpredictable circumstances of everyday life. M. Ehsan Hoque (Figure 2, right), a professor at the University of Rochester who has been working on assistive technologies since his graduate work at MIT’s Media Lab, has been developing systems that he hopes can help people with Asperger’s syndrome or other high-functioning autism-spectrum people improve their ability to interact comfortably in social situations that may be new or unfamiliar.

The system allows people to have realistic conversations, such as a job interview or a first date, with a simulated person on a computer screen. The system provides instant feedback on users’ interactions, including how well they maintain eye contact, how much they fidget or make distracting movements, and how well they maintain an appropriate voice level and tone. The feedback can be displayed directly on the screen as the automated, artificial intelligence (AI) conversation takes place, allowing users to make adjustments as they go along. Hoque and his team have studied ways of providing that feedback as effectively as possible without making it too much of a distraction from the conversation, Hoque explains.

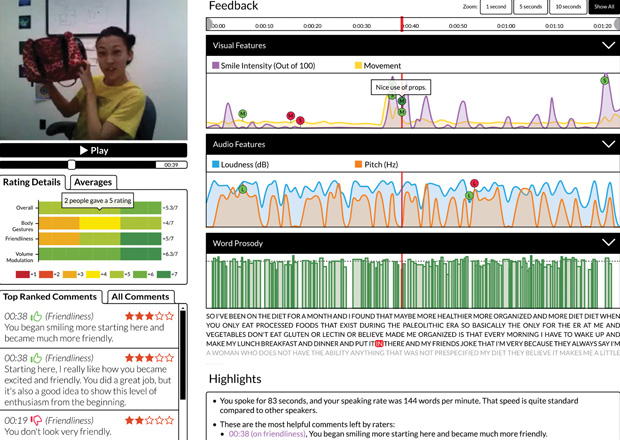

“For example, if I want to say ‘modulate your volume now,’ what’s the best way to provide that information? So we’ve worked on an interface that provides very subtle feedback. And it has some language understanding” (Figure 3). For one set of tests, the team provided a simulated speed-dating set of interactions, in which the research assistant “dates” provided feedback on their encounters. Then, one group received a training session using real-time interaction with a virtual person on screen, a system called LISSA (for Live Interactive Social Skill Assistance).

Hoque says that the initial tests used a simulated AI system with a “Wizard of Oz” setup (a person “behind the curtain,” so to speak), in which the responses were partially guided in real time by researchers. A second group watched YouTube training videos giving advice on social interactions rather than getting the personalized feedback.

Each group then went through another speed-dating session, and their dates evaluated the interactions on a variety of criteria without knowing which subjects had received the interactive feedback. The results showed statistically significant improvements in the scores of those who got the personalized feedback training.

Testing the impact of such systems is challenging, Hoque says, and the initial tests by his group were “the first ones that produced some measurable evidence that people could really improve” through such training: “Showing that this is really having an impact, nobody has done that before.” But even then, it’s difficult to demonstrate the longterm effects: “You give them a task, and they may get better at it. But how do you know that, given a new task, they will be able to transfer the knowledge to the new task?”

Proving that kind of extended impact is a goal of Hoque’s ongoing research. Now, he says, the system has been fully automated, and the new version is being tested and verified in ongoing work. A version of this interactive software, called ROC Speak (Figure 4), is now available free online for anyone to use—whether people with specific communications-related conditions or simply people looking for some coaching before a date or an interview. The system was trained using anonymous feedback from volunteers in the online Mechanical Turk program who evaluated hundreds of sample videos; this feedback was distilled into algorithms the automated system could apply. Users now have the option of just getting the fully automated, totally anonymous feedback or getting additional feedback from real people through the Mechanical Turk program.

The ability of users to keep repeating such interactions—because it is just an online program that will not get bored by the repetition—can make it seem safe and thus encourage sustained practice, Hoque says. He is currently running tests with autistic children to determine whether such a system can help them with effective communication.

The possibilities for using the latest in technology to assist with basic tasks continue to proliferate rapidly, but sometimes that in itself can become a bit overwhelming for parents, teachers, and those working with people on the autistic spectrum. As Abowd says, “There’s a ton of interactive apps, for tablets and smartphones, for example, that help a child build motor skills to do appropriate pointing, or that target different kinds of motor skills, and other kinds of occupational capabilities. There are thousands of them; the issue now is figuring out which of these have any research basis, any data underlying why they work, and a way to say whether your child will benefit from this particular app. That’s the real need right now—to match people to the capabilities of apps.”

Still, among the thousands of apps, websites, and devices, there are already many ideas out there now moving through the pipeline that could dramatically affect people’s lives. And any technology that can help those with autism, of course, affects far more than just the individuals using it. It also changes the lives of their family members, teachers, social workers, and friends, and it opens up worlds of interactions. Tami, mother of the autistic teenager Dillan featured in Apple’s viral video, summed up the impact in an accompanying behind-the-scenes film. “Hearing Dillan’s voice is incredible,” she says. “He’s insightful and smart and creative.” And now, he can let people know that.

Additional Resources

- Informing Families. (2015, July 22). Assistive technologies for social skills. [Online].

- Autism Speaks. Assistive technologies. [Online].

- Autism Spectrum Disorder Foundation. Why the iPad is such a helpful learning tool for children with autism. [Online].

- The Children’s Institute. TCI tech review blog. [Online].

- M. Fung, Y. Jin, R. Zhao, and M. Hoque. (2015, Sept.). ROC Speak: Semi-automated personalized feedback on nonverbal behavior from recorded videos. [Online].

- RocSpeak website. [Online].