La vita percorre sempre; mentre noi spesso ci diventiamo cose quasi perduti nel mezzo del camin.

[Life keeps going on; in the meantime, we often become things almost lost in the middle of the road].

—Max E. Valentinuzzi

Jeden Tag denke ich unzählige Male daran, daß mein äußeres und inneres Leben auf der Arbeit der jetztigen und der schon verstorbenen Menschen beruht, daß ich mich anstrengen muß, um zu gehen im gleichen Ausmaß, wie ich empfangen habe und noch empfange.

[Every day I think countless times that my inner and outer life stands on the work of the current and deceased people, that I must exert myself to the same extent, because I have received and still do].

—Albert Einstein [1]

Recently, during the Christmas season, a friend of mine visited me and, sneaking a look at my bookshelves, found two rather old Nikola Tesla biographies, which I had used to prepare a “Retrospectroscope” column for the then-named IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Magazine when our dear friend Alvin Wald was its editor-in-chief [2]. Eighteen years have elapsed since then; soon, the idea came up of revamping the article. Cynthia Weber, the magazine’s current associate editor, considered it acceptable, and here is the new note divided in two parts: that is, a slightly revised version of the original article followed by new material, including some quite interesting information regarding Tesla’s homes and laboratories. On top of this, Tesla is not devoid of a science fiction touch, as mentioned at the end.

From the 1998 Article

I went through all my years of undergraduate electrical engineering school (1951–1956) without hearing the name Nikola Tesla (Figure 1), even in those courses explicitly dealing with alternating current (ac) machines, or with energy transmission, or with wireless communications. Thereafter, and with a period of overlap between the university and my early professional activities, I spent considerable time (1955–1960) in a private telecommunications company (Transradio International, a subsidiary of RCA Communications). There, I had the opportunity to work with old enough and experienced people— as for example, Jean P. Noizeux—who had been actively involved in the 1920s with point-to-point communications and who had met electrical engineering pioneers such as David Sarnoff. Besides, Noizeux was for a long time the only Latin American IRE Fellow Member. (Remember that the Institute of Radio Engineers, or IRE, was the predecessor of the current IEEE.) Never, in the many lectures we attended as students or the discussions we had, was Tesla even mentioned. However, I do well remember names of other relatively lesser significant innovators in the electrical domain. Several colleagues and former classmates I consulted had similar experiences.

Tesla was a nonentity. At best, a mere remote or vague recollection of some lost incidental reading. These people— professors, electrical engineers, technicians, administrators, all deeply involved in their métier and full of enthusiasm—did they not know the origins of what they were talking about or dealing with daily? Since Tesla died on 7 January 1943 and was active until his end with rather frequent public appearances, many of them might have even had the possibility of meeting him. Is it possible that Tesla was completely overlooked with all of his contributions to their specific fields, and also absolutely ignored in other engineering areas?

At one moment of my life, I was entranced by two books about Tesla, one by Cheney [3] and the second by Seifer [4], and also by an illuminating review of Seifer’s book [5]. How much I learned unexpectedly! These authors are highly qualified and well versed in telling, interpreting, and discussing this outstanding piece of history of modern technology. More precisely, I would call it an amazing piece of history, by far more exciting, provocative, and far-reaching than wars, bloody revolutions, and political upheavals usually covered by tons of printed material.

However, the amount of published material about Tesla is enormous (thus, he is less forgotten than I thought). The number, importance, and transcendence of his inventions and doings are overwhelming, yet current recognition does not seem to abound, although during his lifetime he did indeed receive many honors. Why, then, this state of oblivion? What happened? Can history be so blatantly distorted? Were Marconi and other well-known and reputed men so cynical as to purposefully commit acts of intellectual piracy, as claimed by Seifer in his biography of Tesla?

Nikola Tesla displayed a weird, despondent, and overambitious personality, not precisely a charming one, with an evident tendency to secrecy and a mega-egomaniac attitude, as repeatedly described and documented in the two biographies. In Seifer’s words, Tesla

…did not lie in one plane. He adapted his mental faculties to a number of separate fields, designing fundamental inventions in lighting, electrical power distribution, mechanical contrivances, particle beam weaponry, aerodynamics, and artificial intelligence. He was a journeyman searching for some kind of Holy Grail. His goal was nothing short of altering the very direction of the human species through extensions of his effort. [4]

Shy, he was not! Secrecy was his invariant (~300 patents) and highly irritating modus operandi. Arrogant and hyperself-confident…narcissist? Perhaps, he did not know how to handle properly, within the framework of his superhuman objectives, his lengthy and at times stormy relationships with George Westinghouse and the Morgans (John Pierpont, Sr. and Jr.), collaborators and supporters who made fortunes from his inventions. He humiliated himself and lost face just for the sake of getting financial help for some of his dubious megaprojects (such as the aborted Wardenclyffe station on Long Island, New York).

There is a series of letters, exchanged with the Morgans, which would deeply hurt the dignity and self-esteem of any scientist who, in his or her honest self, would mentally and inevitably take sides with Tesla. Such treatment raises the question of why Tesla accepted such a persistently (years!) sad situation and went along with the Morgans’ constant cold, dry, and peremptory contempt. The Morgans greatly profited from Tesla, but irreverently dismissed him over the years. Tesla, in turn, had the knowledge to stand on his own two feet and use the immense potential power of several of his inventions to obtain the necessary funds to proceed further in his research and development plans, while keeping his dignity and self-respect. However, inexplicably, he did not do so, and, instead, he let himself go into a long and painful downslide, which ended with him in a homeless, pitiful, solitary, and needy old age, persecuted by debts and endless lawsuits and, above all, by resentment and bitterness.

The traditional place for research is the university; it was, it is, and it should always be so, without denying the many contributions made by industry and university–industry collaboration agreements. The former are generous places, and researchers are free to publish their results, while the latter, instead, most of the time have limitations due to patents or privacy requirements. Tesla, regrettably, kept afar from the university environment, full of fruitful and healthy interaction and discussion, where money always takes a second place. Tesla would have had to be more open at a university. We dare say he was afraid of it, probably because he did not like to be questioned, or maybe because he was not sure enough of his own academic background.

Neither Cheney nor Seifer mention this aspect of Tesla’s personality, nor do they give detailed information on his college studies when he was still in Yugoslavia. According to Cheney, his university years were not completed (at the Austrian Polytechnique School in Graz). It appears that Tesla was substantially a self-taught man, which by no means detracts from his stature. Did he ever get a degree, a diploma of some sort?

We suspect Tesla also had a “university degree complex,” and this is not said in any derogatory context. Many people who, for one reason or another, could not successfully finish a systematic academic career later wander through life with mixed feelings, unsure and uneasy of themselves. Instead of the quieter publication in learned refereed scientific journals, Tesla preferred the patent, which is philosophically an antipode of the former, and/or (regrettably!) the flamboyant newspaper article (often written by a lay reporter) announcing sensational findings, some of which were imaginary figments or delusions (his or the reporter’s?). Instead of having students who would become disciples and, thus, be a teacher, he wanted to be the first to own the full rights. He filed one lawsuit after another, always claiming priority and monetary compensation. Sadly, he never did give of himself, displaying instead a covert and overt lack of generosity.

Nonetheless, there are documents indicating he did not care much about money. Lee De Forest (1873–1961), a brilliant engineer with solid academic grounding, admired him and tried several times to work for and with him, but Tesla systematically turned him down. Had he associated with De Forest, his future would have probably been completely different. According to Carlson’s book [12], however, Lee De Forest and a collaborator named Abraham White created a wireless company scam on Wall Street that made it difficult to get investors to finance Tesla’s wireless projects. De Forest got entangled, too, with the early film industry, had a controversial way of acting, and ended up facing many failures. Two great minds unable to formalize a productive association!

Such an attitude (Tesla’s) was, in the end, self-destructive, for no one can work and produce successfully in utter isolation; even Einstein, who had also a tendency to work alone, consulted and participated actively in the scientific community. Looking back in retrospect, we dare say that in spite of his tremendous technological contributions (even in medicine, in X-rays, and in diathermy), Nikola Tesla was neither successful nor accomplished, and, definitely, he was not a true scientist of traditional lineage, a sad conclusion, indeed.

Science and technology evolve in a continuing dynamic process. Many times, an idea that is just ripe will crop up in any place and at any moment because it has followed a long-trodden road, accumulating the knowledge of generations. Thus, almost simultaneous and yet perfectly honest, independent discoveries may take place. This is one reason that the history of science and technology is so highly enlightening. James Clerk Maxwell first, in 1865, and Heinrich Rudolph Hertz later, in 1880, respectively, offered to the world the electromagnetic equations and waves [6], [7]. Engineers, scientists, inventors, and financial tycoons, one way or another, used these magnificent concepts freely, egocentrically, and painfully. Many times, these concepts were exploited without realization of their genesis or even without recognition of the names of these two giants.

It is perhaps an overstatement to credit Tesla with such enormous achievements, both in number and in variety, based solely on dates of patents and/or legal court decisions, and so understate the contributions of that unheralded mass (often also forgotten) of earlier and contemporary scientists. If things are pushed too much, we might say that many inventors (including Tesla) were inspired by that primogenitor of engineering, Leonardo da Vinci, for he anticipated and even designed machines of different sorts (as for example, the flying machine) [8]. Technological developments are lengthy and complex processes, where usually several hands leave their fingerprints.

Since we recall Leonardo, there are striking similarities (and profound differences, too) between him and Nikola: extremely high intellectual productivity, even dreams (some came true); passion for concealment; did not form families and were not sexually active; love for their mothers and surrounded by unhappy childhood events; tendency to isolation; way ahead of their times; and both engineers. Leonardo was also a consummate artist who, unlike Tesla, did not want to transcend and, thus, concealed as much as possible.

Perhaps this forgetfulness of scientific history is nothing but a manifestation of the obliteration phenomenon described by Eugene Garfield [9]. The said knowledge is so completely and well embedded into society that there is no need to recall or to cite the author. A typical example is the Theory of Relativity. References to Einstein as its recognized originator have steadily and sharply declined over the years. By the same token, do we remember Edward Jenner, or Jonas Salk, or Albert Sabin when our children receive the smallpox or the poliomyelitis vaccines (even more so now that the smallpox virus has been virtually eradicated and children are no longer vaccinated)? Do we refer to Gutenberg when we buy a book? Do we honor Archimedes when we swim or travel on a boat?

The most conspicuous feature in the character of Galileo and the cause of his tragic downfall was vanity and a hypersensitivity to criticism, combined with sarcastic contempt for others: a fatal blend of genius plus arrogance minus humility [10]. Our modern scientists would well remember that such a character flaw is inherently destructive to both science and the individual. The history of knowledge abounds in examples of all sorts, as well-documented by Arthur Koestler [10].

Once more, the overall edifice of knowledge was built, and is built, in steps—sometimes shorter, sometimes longer; with bricks contributed by many, sometimes with columns and beams contributed by a few, across trials and errors, painfully and joyfully, but always leaving ample windows and gates to let the light and fresh air come freely in.

So far, so much for what was said before. Let us go now into information that is more recent to better clarify former events.

New Material About Tesla: Books, Publications, Places, and Even Science Fiction

Not long ago, Christopher Cooper produced a new biography of Tesla [11] (see also Tesla Books). Cooper, rightly and again, says that for years this genius was relegated to relative obscurity, his contributions darkened or concealed by several 19th-century inventors and industrialists who took credit for his work or stole his patents outright. Somehow, and fortunately, this situation has been nearly fully corrected, and Tesla has finally been given his due. In recent years, there has been an explosion of interest in the quixotic inventor.

One of the authors of this article, Martin Hill Ortiz (see his blog posts on Tesla here), has undertaken a fair amount of research regarding Tesla and 19th-century Manhattan. He found details that pinpoint the location of Tesla’s East Houston Street laboratory, its history, and what became of it. On 13 March 1895, Tesla lost all of his work in a fire (Was it an arson’s fire? Tesla had powerful adversaries) that almost completely gutted the six-story and basement building at 33 and 35 South Fifth Avenue (now called La Guardia Place), south of Washington Square Park, in the New York University vicinity. He occupied the entire fourth floor. When the floor gave way, his apparatuses fell to the second story, where they lay in unrecognizable ruin.

Bernard Carlson’s biography of Tesla describes thus [12]:

With his depression finally waning, Tesla rented a new laboratory on two floors of a building at 46 East Houston Street in July 1895. [Just six months after the fire.]

This address is referred to as 46–48 E. Houston in Tesla’s correspondences. The address was located on the north side of E. Houston, just east of the corner of Mulberry and two blocks east of lower Broadway; his lab remained there until 1902, when he started moving operations to Wardenclyffe. This was a new seven-story building, and Tesla’s new laboratory occupied the two upper floors. On the Tenement Museum blog (one will have to search the site to find the relevant material there), Liana Grey did some excellent research into the history of this section of neighborhood. In 1894, the building occupying this space was torn down. The old building was called Dramatic Hall and had descended from theater to dance hall to a nightly abode of an army of tramps.

Tesla spent nine months in Colorado Springs, March 1899 to January 1900, invited by his patent attorney. There, he laid the groundwork for his wireless communications and power transmission work, producing over 500 pages of laboratory notes. In all likelihood, these notes provided original information later on used in his autobiography (mentioned below).

However, and unfortunately, bad luck seemed to chase Tesla. Two months after his return from Colorado Springs and five years after the first fire at S. Fifth Avenue, the following sad news appeared in a professional magazine [21]:

Fire in the seven-story building at 46–48 East Houston Street early Thursday morning damaged many of the early delicate models and machines in the laboratory of Nikola Tesla, the inventor. What the damage is cannot be told yet, as Mr. Tesla is the only one who knows their value.

The building survived, standing from 1895 to 1929. Figure 2 is a drawing of the area; Tesla’s new laboratory building appears highlighted in yellow. In 1902, Tesla started moving this Houston Street laboratory 60 miles east out to Wardenclyffe on Long Island.

![Figure 2: The yellow building on the north side of Houston Street, between Mulberry Street and Mott Street, is now a five-story residential apartment building with a large CVS chain pharmacy on the street level facing Houston Street [18].](https://www.embs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/valentinuzzi01-2606472.jpg)

Most interesting is Tesla´s autobiography. Tesla was 63 years old when this text was first published in The Electrical Experimenter magazine in 1919. It is a short text, easily accessed [17], enlightening and worth reading, especially because his own words tell the events and the ideas, not a minor fact since he had not many publications of the kind: an unfortunate fact, for otherwise, we would have had better information about his ideas and production.

Tesla’s Laboratories

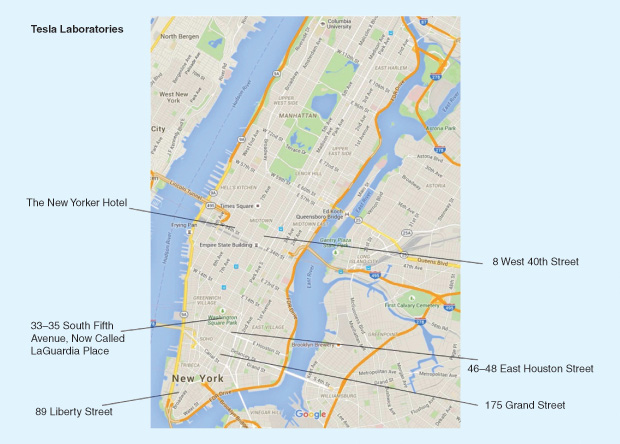

Tesla’s places could hardly be fully listed in a separate chapter, let alone a couple of paragraphs. He worked at various laboratory sites after his arrival in the United States. (Tesla traveled to the States in 1884, when he was 28. The voyage appears not to have been a happy one; a mutiny of sorts occurred on board, and Tesla was nearly knocked overboard [4]. Mankind could have missed many inventions!) All but two of seven of them were in the area of lower Manhattan (Figure 3). A century has elapsed, and the local landscape looks very different.

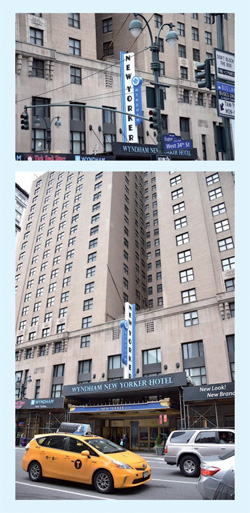

Right, Figure 4: At West 34th Street and Eighth Avenue stands the hotel where Tesla lived for years, where he used to take in and care for wounded or sick pigeons. It was one of his favorite hobbies, which the hotel management did not forbid him to practice, probably out of respect to the already well-known inventor. (Photo courtesy of Daniel Cervantes.)

The photos in Figures 4 and 5 were taken very recently and show, respectively, the New Yorker Hotel’s current façade and the small memorial room inside the hotel remembering and honoring Tesla— a nice hidden spot that not many people are aware of. According to the hotel administration, Tesla was one of the most idiosyncratic guests ever to stay with them. All his requests were in numbers divisible by three (napkins, slices of bread). Even his room number, 3327, had significance: 3³ = 27.

Figure 6 shows how the northeast corner of East Houston Street and Mulberry looks today, perhaps, in several respects, the most relevant place where Tesla worked. A pharmacy is located there now, and a moved and very excited Daniel Cervantes went in with his Colombian wife, Elena Castro, and asked questions to its owner or manager, who, not surprisingly, did not know a word about Tesla. Modern cars and busy hurried people walking by replace the scenery of the probably quieter old environment, complete with horsedrawn wagons. It was impossible not to feel some kind of longing or respectful sadness, noted Cervantes.

Following is a list of Tesla’s laboratories and their locations [16]:

- 89 Liberty Street (1887; he reported the invention of the ac induction motor here)

- 175 Grand Street (1889)

- 35 S. 5th Avenue, now 539 La Guardia Place (1890–1895; completely destroyed by fire)

- 46/48 East Houston Street (July 1895–1899/1902; fire in 1900, but the laboratory survived; he started moving this lab to Wardenclyffe in 1902)

- Wardenclyffe, Shoreham, Suffolk County, Long Island (1902 to ~1911; partial abandonment foreclosure for debt, 1915; tower demolition 1917, property for sale to recover debt 1922)

- Queensborough Bridge, 59th Street near 2nd Avenue (1905; disputed location and activities).

Tesla’s Offices

Tesla’s companies had business offices; notice these appear after his laboratories close, except for Wardenclyffe.

- 165 Broadway (now 1 Liberty Plaza—ground zero; 1905)

- 233 Broadway, #1136, Woolworth Building, (1914; tallest building in Manhattan at the time)

- 1 Madison Avenue, #202–203, Metropolitan Life Tower (1914)

- 8 West 40th Street, #2006 (1915–1924)

- 50 Madison Avenue (old Conde Nast headquarters between 44th and 45th Streets; 1925).

The other New York metropolitan area location (60 miles east from Manhattan) where Tesla built a laboratory is Shoreham, Long Island; there the Wardenclyffe Tower construction was almost completed. Tesla essentially ran out of funding but not out of ideas. Marconi successfully transmitted Morse code across the Atlantic, De Forest and Abraham White had scared Wall Street investors from wireless, and Tesla had a 51% deal with J.P. Morgan that further soured the chances of outside investments into his dream for global communication and power transmission. To convince Morgan to keep financing him, Tesla described the way the Wardenclyffe project would bring about personal informatics (much the way it is today). Coincidentally, Wardenclyffe is relatively close to the currently important U.S. Department of Energy, Brookhaven National Laboratories in Upton, New York.

![Figure 7: The Tesla Science and Technology Center and Museum on Long Island. (a) The remains of the Tesla Tower base and laboratory building at Wardenclyffe after removal of the tower can be seen [19]. (b) A picture taken April 2016 by daniel cervantes of what was the original tower base. This tower (1901–1917), also known as the Tesla Tower, was an early wireless transmission station designed and built by Tesla in Shoreham, New York, in 1901–1902. He intended to transmit messages, telephony, and even facsimile images across the Atlantic to England and to ships at sea, based on his theories of using the earth to conduct the signals. The tower stood 57 m tall and had a shaft that extended 37 m below ground with radiating tunnels to “get a grip on the earth” [20]. (Photo courtesy of Daniel Cervantes.)](https://www.embs.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/valentinuzzi06-2606472.jpg)

Tesla’s 841 m² laboratory at Wardenclyffe was designed by his friend, the architect Stanford White. The red brick building, the last and only remaining of Tesla’s laboratories, is still standing in good condition. In front of Tesla’s laboratory, one can see the foundation of what was the original Wardenclyffe Tower base (Figure 7). The building and surroundings are now part of the Tesla Science Center at Wardenclyffe, under the direction of, among others, Jane Alcorn (president), Margaret Foster (board member), and Gene Genova (vice president), its devoted curators.

The Tesla Science Center is a not-for-profit organization that succeeded in purchasing the Tesla property in May of 2013 with the help of Matthew Inman (theoatmeal.com), collecting US$1.37 million via an Internet fundraising campaign. This was of paramount importance, considering that at one point its demolition was likely. Since the acquisition of the property, groups of passionate volunteers are meticulously cleaning up the area as part of the ongoing restoration efforts. (“The Oatmeal” is a comics and articles website created in 2009 by cartoonist Inman, who uses the comic’s name as his nickname. Inman is from Seattle, Washington.)

A statue honoring Tesla stands facing the original tower base (Figures 8 and 9). The following legend can be read on the pedestal:

Were I to have the good fortune to implement at least some of my ideas, it would be for the benefit of the entire humankind, if my hopes come true, the sweetest thought would be that it was achieved by a Serbian.

–Nikola Tesla

This, indeed, is a very powerful statement revealing his altruistic convictions for the use of his ideas.

Was Tesla a great scientist? Or a genius? Maybe our standard institutionalized definitions to categorize a great thinker of his caliber do not apply to him; maybe he went even further, above and beyond those definitions. He certainly had brilliant, world-reaching ideas for the well-being of others. On top of everything else, let us underline that he was fluent in eight languages: Serbo-Croatian, English, Czech, German, French, Hungarian, Italian, and Latin. Such a person is called a hyperpolyglot. Do titles and degrees really matter at such an intellectual level?

As the strawberry on top of the ice cream, we may recall the famous Frankenstein story (or The Modern Prometheus), by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley (1797–1851), who inaugurated the science fiction style in 1818—almost 200 years ago. Mary Shelley created the story on a rainy afternoon in 1816 in Geneva, where she was staying with her husband, the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley, and another great poet, their friend Lord Byron (1788–1824). Byron proposed they each write a ghost story, but only Mary Shelley completed hers. The Bakken Library and Museum, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, keeps an original copy of the first edition of the Frankenstein book [13].

By several literary standards, the novel lacks in many respects, as often pointed out by the people who know; however, it has three outstanding characteristics: a great idea that taps into modern fears, a great central story, and one great enduring character—the monster. No wonder, then, that it has traversed time and garnered lasting fame. In a modern science fiction thriller [14], Nikola Tesla came up as the perfect first actor of a similar tale (who else could it be?), along with Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930). Together they face the multimurderer Dr. Henry H. Holmes (a distorted monstrous version of Sherlock, the keen detective). Thus, Doyle, Tesla, and the madman Holmes engage in a deadly game of wits, in a new and ingenious fictional story.

Conclusions

Society viewed Tesla as many things: inventor, artist, physicist, businessman, genius, peculiar in appearance and behavior— and he was all those things and more. He had one great success, the ac motor, and one great unsuccessful attempt, radio communication. He understood how technology can advance and change society for the better. He knew the way in which technology was presented had a lot to do with how well it was accepted, advanced, and adopted; and this is still true today. He lived at a key point in the history of technology and society. Electric power and electronics have had major impact on society so far, with still more to come. Tesla tried to be critically active in power, wireless communications, and wireless power transmission.

Tesla´s achievements were impressive, long-lasting, and of the highest social and economic impact. His particular personality, though, prevented him from being recognized in the academic environment and surrounded by student disciples. Besides, many people took obvious advantage of him and maliciously overshadowed him, condemning him to a state of quasioblivion. Fortunately, this situation is being slowly taken care of by recovering his name. We are able now to assert that justice has been very nearly done. Regular electrical and communication engineering courses should remember him in their current lectures. On top of all this, he had some contributions in the medical sciences including electric currents in the body, so that, in a sense, we can also affirm that Nikola was a biomedical engineer.

To finish, a new literary avenue opened up, well suited for his amazing personality and, as a kind of commemoration, two centuries after the science fiction style was created. An enormous amount of material (including legal transcripts) relevant to Tesla’s life and work can be accessed by the interested reader from [22].

Tesla had already changed the direction of the developing electric power industry with the ac induction motor. He had Wall Street funding, but there was more trouble ahead for his grand plan to significantly change the world for the better with limitless free power and instantaneous global communications. From this point on, his plans did not much come true. Marconi beat to an important milestone of transatlantic wireless transmission in December 1901, and he could not recover in the eyes of the establishment. He knew how to swim in uncertain waters, and he understood how to leverage financing to get new technology adopted; however, in the later part of his life, his peculiar way of being did not help him succeed.

References

- A. Einstein, Mein Weltbild [My Vision of the World]. Berlin: Verlag Ullstein, 1934, p. 7.

- M. E. Valentinuzzi, “Nikola Tesla: Why was he so much forgotten and resisted?” IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Mag., vol. 17, no. 4, pp. 74–75, Jul. 1998.

- M. Cheney, Tesla: Man Out of Time. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993.

- M. J. Seifer, Wizard: The Life and Times of Nikola Tesla. Biography of a Genius. Secaucus, NJ: Birch Lane Press, 1996.

- R. Kline, “Reviews and Commentaries: An updated history of cryptology ‘forgotten genius’ Nikola Tesla; archaeological eyewitnesses,” Scientific Amer., vol. 276, no. 4, pp. 108–112, Apr. 1997. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican0497- 108.

- C. A. Culver, Theory and Applications of Electricity and Magnetism. New York: McGraw Hill, 1947.

- M. E. Valentinuzzi and A. J. Kohen, “James Clerk Maxwell, Kirchoff’s laws, and their implications on modeling physiology,” IEEE Pulse, vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 40–46, 2013.

- L. Da Vinci, The Notebooks of Leonardo Da Vinci (Abridged), E. MacCurdy, transl., R. N. Linscott, Ed. New York: The Modern Library, 1957.

- E. Garfield, “The ‘obliteration phenomenon’ in science—and the advantage of being obliterated!” Current Contents, no. 51/52, pp. 5–7, Dec. 1975.

- A. Koestler, The Act of Creation. London: Picador by Pan Books, 1978.

- C. Cooper, The Truth About Tesla: The Myth of the Lone Genius in the History of Innovation. New York: Race Point Publishing, 2015.

- W. B. Carlson, Tesla: Inventor of the Electrical Age. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press, 2015.

- M. E. Valentinuzzi, “Why study the history of BME, science and technology?” IEEE Pulse, vol. 2, no. 1, pp 45–47, 2011.

- O. M. Hill, A Predator’s Game. Tucson, AZ: Rook’s Page Publishing, 2016.

- L. I. Anderson, Ed., Nikola Tesla. On His Work with Alternating Currents and their Application to Wireless Telegraphy, Telephony, and Transmission of Power. Breckenridge, CO: Twenty-First Century Books, 2002.

- V. Abromivic’, Tesla and the Rise of Spiritual Physics. Belgrade, Serbia: Tesla-Patens Institute Publishing, 2015.

- N. Tesla, My Inventions: The Autobiography of Nikola Tesla. [Online]. Available: http:// www.teslasautobiography.com/

- New York Public Library. (1904). Bird’s eye view of New York city. [Online].

- Tesla Wardenclyffe Project. [Online].

- Wikipedia. Wardenclyffe Tower. [Online].

- Western Electrician Mag., p. 179, Mar. 1900.

- Tesla Google Drive. [Online].