With the ubiquitous nature of smartphones, apps are a regular part of our day-to-day lives. They are also becoming a larger presence in health care, where they have the ability to expand access to care, help people monitor health changes, provide support for people living with chronic conditions, and coordinate communication between patients and their doctors. From detecting skin cancer to helping people with diabetes, new apps aim to change how people think about their health.

Etta: Stopping skin cancer on the spot

According to the Skin Cancer Foundation, skin cancer is the most common cancer worldwide, and more than two people in the United States die from skin cancer every hour. Fortunately, catching skin cancer early can save lives, and technology can help with early detection.

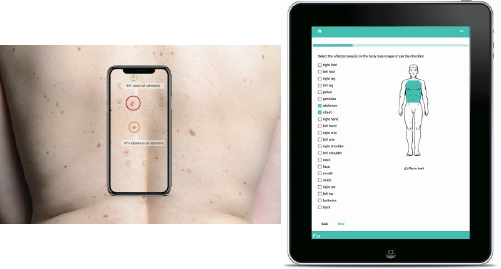

Apps created by the Colorado-based company Etta use artificial intelligence (AI) to help patients and physicians identify potentially cancerous skin lesions and other skin conditions (Figure 1). To use the consumer Etta app, a person takes photos of concerning spots. Etta compares the user’s images to thousands of hospital-verified images and provides an instant risk breakdown of potential lesion types. Users with potentially cancerous moles are encouraged to book a telehealth appointment with a dermatologist.

“The fact that they can then follow it up with a teledermatology visit is helping more people get into the clinic,” says Charu Singhal, Etta’s CEO and cofounder. She notes that this is especially useful for patients who live in rural areas who cannot afford to take a day off of work to drive to a dermatology clinic. Within the first 3000 users of the app, Etta detected 44 cancers that were later removed. “That was a pretty exciting start,” says Singhal.

The premium version of the consumer app also allows users to track and monitor skin concerns over time. This means patients can see whether their moles have changed size or shape between dermatology appointments and provides a record of these changes that they can share with their doctor. “Something that we found is that there are a lot of people that get skin cancers pretty regularly and that are looking for options and ways to track and are also feeling lost in the system,” she says. “It was really eye opening.”

Besides the consumer app, Singhal has partnered with dermatologists to develop an app for clinical use, which helps clinicians identify which lesion should be biopsied first. Etta also has a tool that can be used in emergency and primary care to help identify rash features and build dermatology consults with the correct terminology and most salient features.

Training AI algorithms for different skin conditions and on different parts of the body has required amassing libraries of clinically verified images. For Singhal it has been important that the images used to train Etta’s algorithms represent different skin tones. “That was always a priority for us,” she says, noting that she was originally inspired to create the app after her friend, who had darker skin, died from skin cancer. “Darker skinned people are just not identified in time in terms of cancers.” She also notes that rashes are not red on darker skin, which is another reason why it’s important to have a diverse set of images to train Etta’s algorithms. “The AI is only going to be as good as the dataset, it is only going to be as ethical as the dataset, as non-biased as the dataset,” she says.

Pearlii: Expanding access to dental care

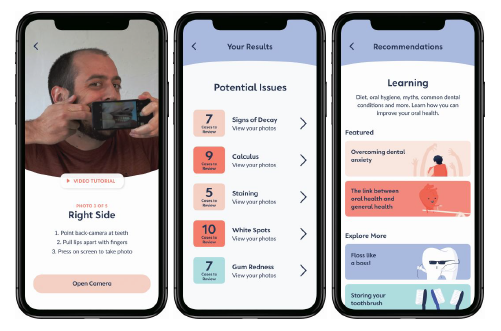

“I’ve got really bad teeth,” says Kyle Turner, Ph.D., founder and CEO of Pearlii. “I grew up in a very poor family in rural remote Australia with no access to dental health services. We didn’t know about oral health or oral hygiene.” Turner’s teeth, along with his fondness for machine learning and a background as a public health epidemiologist, inspired him to create Pearlii, an AI image processing app that scans photos of teeth for dental problems such as tooth decay and gingivitis (Figure 2). Pearlii is Turner’s way of expanding access to dental health care. “Most oral diseases are fully preventable with regular checkups and good oral hygiene, but the dentist is really expensive. It’s pretty inconvenient. It’s sort of a thing of privilege,” he says, noting that 65% of Australians have not been to the dentist in the past two years.

To use the app, a user takes five photos of their teeth and uploads them. “Within about four seconds, we’ll scan those with an algorithm that we created that was trained by six different dentists,” says Turner. “It’s a free, fast dental checkup.” Originally the app’s algorithm was trained to spot tooth decay but has now been trained on about 15 different dental conditions. “We’re building the dataset to improve the algorithm,” says Turner. “Whatever a dentist can diagnose or detect by looking in your mouth, which is most oral diseases, we believe we can train an algorithm to match.”

If the app detects a problem, it suggests oral health challenges and encourages users to make an appointment with a dentist. Pearlii has partnered with over 3000 dentists in Australia for referrals and plans to eventually partner with dentists in the United States. The app is free. Pearlii makes money through its dentist referrals and by selling whitening kits. For every whitening kit purchased, Pearlii funds dental supplies for a child in East Timor.

Pearlii launched its beta app in November 2020 and has raised 1.25 million in seed funding. The team plans to add gamification and expert content from orthodontists and dentists. Turner also wants to return to his research roots and perform clinical studies with the app. So far the response from dentists to Pearlii has been positive, according to Turner. “Early on there were a few skeptics, but they’ve come around,” he says, adding that the app is a lead generator for dentists. “We’re not a replacement for a dentist, we’re a support, a self-help tool,” says Turner. “We want more people going to the dentist earlier so they have less pain and less cost in the long term.”

Epsy: Empowering people with epilepsy

The Epsy app from Epsy Health, a part of the medical device company LivaNova, helps people with epilepsy monitor their symptoms and get support (Figure 3). People with epilepsy are often asked by their doctors to keep a diary of their seizures and seizure triggers. “The majority of people don’t do it, and the ones that do write these enormous bibles,” says Marco Peluso, vice president of Epsy, digital epilepsy. “A doctor will either find themselves completely flying blind with no reliable information from the patient or they have too much information in a format that is not digestible.” Epsy aims to make entering and reading this information easy and effortless.

Besides input actively logged by users—like seizure triggers and medication side effects—the app can also collect data about activity and sleep. Epsy presents these data in a way that allows users to make connections between their behavior and their epilepsy. Data are kept private unless a patient wants to enable sharing their information with a specific physician. “Now before every visit [the physician] can go and quickly review the same information that you have on your phone,” says Peluso. “You and the physician suddenly are on the same page.”

Peluso hopes that simplifying how information about seizures and potential triggers is presented will improve patient care. “There is an opportunity for technology to, maybe somewhat counterintuitively, make health care more personal… you free up the time to actually take care of the patient rather than just focusing everything on the disease,” says Peluso. He thinks that when doctors and patients have more easily accessible information it might also help speed the time it takes to get seizures under control, a process that can take years.

There is also a community component of the app where people with epilepsy—or caregivers for people with epilepsy—can connect with other people who are going through similar experiences, like being diagnosed with a rare form of epilepsy or preparing a child with epilepsy for summer camp. The goal says Peluso is to empower people with epilepsy so they can understand their condition better and live their lives with optimism.

The Epsy team is currently looking into ways to improve the app and is exploring creating a platform to support scientific research on epilepsy. “We feel like we’re just barely getting started. There is just so much opportunity for innovation, and we are getting these very warm responses from our users telling us how they love the app,” he says. “One of the rewarding things about building something good in digital health is that you’re actually helping people, and you are improving their lives.”

Quin: Helping people with diabetes make decisions

Quin is a personalized, self-management app designed to help people make decisions about how to manage their diabetes. “These are people that have to make over 180 decisions day in, day out about living with diabetes,” says Barry Rogers, head of product at Quin (Figure 4). The name Quin is a portmanteau for “Quantifying Intuition.”

“What we want is people to come into the app before they have decided what actions to take,” says Rogers. For example, if a person wants to eat a particular snack after working out, they can visit the Quin app and see what usually happens to their blood sugar in that scenario. “We’ve summarized all of their past actions, finding the ones that are most relevant, and then surfacing that to them at the point they make a decision,” says Rogers. The app marries data manually inserted by the user—such as what they have eaten and the amount of insulin they have taken—with activity data from their phone since exercise can affect blood sugar.

Quin can also help users better understand how the level of insulin in their blood changes over time. “Something that absolutely astounded me when we were doing research was the amount of people that don’t understand how long their insulin lasts for in their own body,” says Rogers. Rogers says displaying this information stops people from taking too much insulin when they are concerned that their blood sugar is not going down fast enough. “We’ve actually helped a lot of people reduce their number of hypoglycemic events,” he says.

Rogers stresses that the app cannot predict the future. “There are over 42 factors that can affect your blood sugar and at the moment we can maybe track two or three of them,” he says. This means that Quin is not designed to tell people what actions to take. “One of the challenges of living with diabetes is you’re constantly told what to do,” says Rogers. “We always want to empower the user of the app, they’re the ones who should be making the decisions.”

The more information a user feeds the app, the more personalized it gets. In the future, the Quin team hopes to integrate other factors that influence blood sugar into the app, such as sleep, menstruation, heart rate, and cortisol levels. They are also planning on building in support messages and a guide to help users experiment with new foods.

Currently the app is available on iOS and in the United Kingdom and Ireland. There are plans to add an Android team in the next year and to expand the app to the U.S. and other countries in 2021–2022. The team wants to make sure the app meets the regulatory requirements before launching in new countries and to be aware of country-specific information that could affect users of the app, such as the challenges of affording insulin for many people with diabetes in the United States.

Despite this limited roll out, Quin is already one of the top three diabetes apps in the U.K. “It shows the power of what we’re doing,” says Rogers. “We are different and so people are starting to see that difference.”