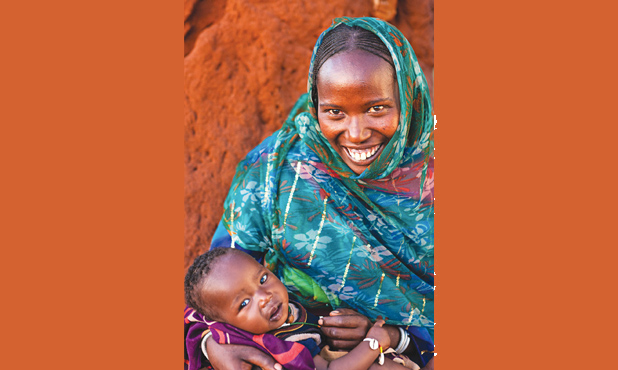

The fact that every 90 seconds, somewhere in the world, a woman dies during pregnancy or childbirth is simply unacceptable. What is even more shocking is that most of these deaths are preventable if appropriate care is available. The death of a mother is not only the end of a life; instead, it is most often the beginning of a dark and difficult future for the whole family and the aftershocks affect the community at large. Children, particularly in developing countries, who lose their mothers early on are less likely to be productive members of society, are likely to be malnourished, and face lifelong social and economic challenges.

Current and Emerging Solutions

Engineers, technologists, and scientists have developed remarkably potent and effective tools to make dramatic improvements in maternal health in the developed nations, where childbirth and subsequent care is no longer a time of misery and morbidity but is a time of celebration and joy. Yet, resource-limited countries are still suffering heavily under the burden of poor maternal health. The issues of access, cost, scalability, and ease of use in diagnosing, managing, and addressing high-risk conditions still plague health systems across a vast majority of the developing world.

That said, recent years have seen an increase in technologies and solutions to address this gap. The solutions, driven largely by engineers and innovators, can be classified into four broad categories. These categories are not meant to provide an extensive review of all technologies and solutions but instead are aimed at providing an overview of emerging trends and the gaps they may be able to address.

From mHealth to PharmaChk

First, driven by a rapid increase in the availability and use of mobile phones, the relatively new domain of mobile health (mHealth) has provided mechanisms for data collection, information dissemination, and, in some cases, diagnosis through direct measure or remote consultation. With the availability of smartphones, new algorithms available in local languages have provided patients and caregivers with the ability to collect information about pregnant mothers, identify early signs of complications, provide information about health checkups, keep track of progress during pregnancy, and provide care after pregnancy. These tools, on one hand, have given caregivers the ability to automate information collection and, on the other hand, have provided policy makers and ministries of health with population- level data that are critical for improved governance and better focused policies for improving maternal health. (Zaineb Suleman’s article “Journey of a Thousand Miles” in this issue of IEEE Pulse discusses the development and implementation of one such model in rural Pakistan.)

Despite the substantial growth in mHealth, the use of mobile phones to diagnose conditions in maternal health has been relatively limited when compared to other infectious diseases such as malaria and HIV.

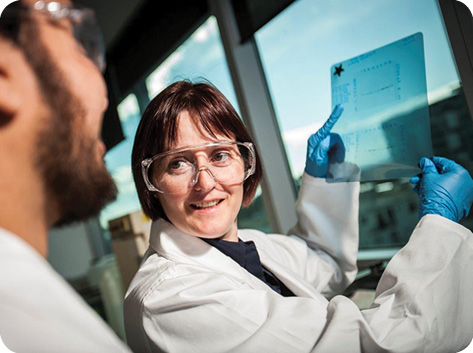

The second category of innovative solutions for mHealth applications is associated with low-cost alternatives for the early detection, diagnosis, and management of disease and pregnancy complications. These tools are aimed at providing high-level care, robust diagnosis, and context-appropriate disease management at a cost that is accessible in low-resource settings. Low-cost optical technologies for pathology and imaging; low-cost and robust continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machines and oximeters for newborn and neonatal health; and microfluidic and rapid diagnostic systems for serum, saliva, blood, or urine testing for infections would fall into this category.

The development of technologies in this arena has been boosted by a combination of factors. First, there is an increase in appreciation of the complex challenges facing developing countries among researchers and students in engineering and science. Second, there have been some initiatives facilitated by governmental and nongovernmental agencies (such as the multi-institutional and multigovernmental initiative Saving Lives at Birth) that have provided support for novel and transformative ideas to be developed and optimized. Third, and perhaps most importantly, the development and high proliferation of research in microfluidics has provided researchers with the opportunity to design for complex environments with an urgent need for pointof- care devices. The widespread use of rapid diagnostic malaria kits in Africa is an example of a point-of-care technology that is creating an impact on disease diagnosis and improving overall health outcomes. Although these factors have increased the portfolio of technologies for global health applications, the scale-up of these promising technologies continues to be a challenge.

The third category of innovations deals with improved drug delivery, efficacious drug discovery, and treatment paradigms. Here, there have been few but promising developments associated with drugs that do not require cold-chain (which is often difficult to maintain) conditions, are stable for longer periods of time, and are easy to administer in the absence of centralized health care facilities. Oxytocin, a key drug to treat postpartum hemorrhage in both the developing and developed world, is currently administered intravenously and is known to be unstable in high heat and can lose its efficacy. Approaches developed by researchers to provide inhalable solutions or to administer it sublingually may circumvent the current challenges and make a substantial impact on saving maternal lives during and after pregnancy.

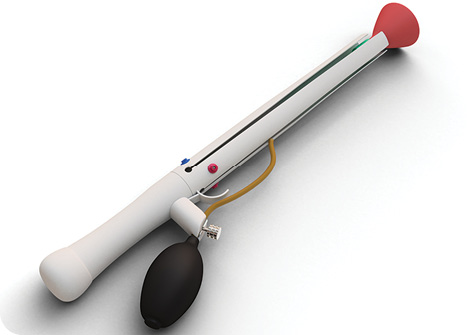

Similarly, the Odon device, a simple technology developed by an Argentinian car mechanic and innovator, has the potential to ease the process of delivery of a fetus when there are complications in the second stage of delivery. The device is made of a film-like polyethylene material and is safer and easier to apply than forceps and a vacuum extractor (contraindicated in cases of HIV infection) for assisted deliveries. The device also offers a safe alternative to some cesarean sections in settings with limited surgical capacity and human-resource constraints.

Once again, the challenge facing technologies in this category is that of scale-up. Fortunately, for the Odon device, the medical technology company BD Biosciences has partnered with the innovator for trials and scale-up. Similarly, the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline has partnered with Australia’s Monash University to further the process of development and testing for the inhaled oxytocin solution. While these partnerships are promising, there needs to be a stronger effort by both the public and the private sector to create opportunities for clinical trials, field testing, and scale-up, without which the impact of these technologies will remain limited.

The final class of innovations falls into the category of strengthening the system and increasing its capacity. For example, technologies such as the We Care Solar Suitcase used in several African nations, including Uganda, Malawi, Sierra Leone, and Ethiopia, are able to provide doctors, midwives, and nurses with medical lighting and power for obstetric care and emergency procedures needed to save maternal lives. Systems such as the solar suitcase that use solar panels to generate and provide power can increase the ability of small and rural facilities to provide health care in the absence of reliable power. Similarly, other technologies such as PharmaChk, a portable device that can detect and quantify active ingredients in medicines and their dissolution, are providing regulators and pharmacies with the ability to test the quality of commodities needed to save precious maternal lives. The success and sustainability of a health system depends greatly on integration and coordination across various stakeholders. The technologies and solutions in this category are, therefore, essential for the sustainability and impact of technologies listed in the first three categories described earlier.

Coordinating Efforts for a Healthier Future

Despite promising activity in various innovation sectors, the current state of maternal health in the developing world is unacceptable. Too many precious lives are lost, leaving behind a difficult future for the families in particular and societies in general.

The good news, despite the grim statistics, is that we have the power to change the status quo. Most maternal deaths are preventable, and we have a good understanding of when interventions can mean the difference between life and death. Unfortunately, these interventions do not get to the right people at the right time due to cost, access, and geographic and sociocultural barriers. The challenge, therefore, lies in developing technologies and solutions that are context appropriate, financially affordable, and broadly accessible. As mentioned earlier, there are a number of solutions that are being developed and piloted in various parts of the world, yet many face uncertain futures due to scalability challenges, lack of capital, absence of commercial partners, and poor understanding of the local socioeconomic landscape. The success and impact will therefore not be possible without a coordinated, integrated, and multidimensional approach that involves strong scientific and technological foundations and robust implementation strategies. Therefore, if we are serious about solving the difficult and complex problems of maternal health, we need a bold approach that is both top-down and bottom- up, integrates the many facets of technology with strong financial planning, and is able to work within the socioeconomic realities of the desired communities.

Fortunately for the engineering community in general and the biomedical engineering community in particular, coming up with affordable, accessible, and optimally designed solutions that are scalable is well within reach. Therefore, the ability to improve maternal health globally, to save countless lives through ingenuity and scholarship, and to engage biomedical engineers in this truly global problem should serve as a catalyst for more research in this area.

In the end, given recent developments in optics, microfluidics, and mHealth, there is a reason to be optimistic about the future. There is a strong momentum to save countless lives, and we need to capitalize on that. Maternal health will be one of the many beneficiaries of an engaged, motivated, and talented pool of transformative thinkers if we provide leadership, support, and outreach. The lasting impact of our effort will be on the future generations, who will get to experience a better tomorrow through the work, intellect, and effort of their globally innovative, socially conscious predecessors.