In August at EMBC15 in Milan, Dr. Domenico Laurenza, of bgC3, Kirkland-Seattle, USA and the Museo Galileo, Florence, Italy, will deliver a keynote speech entitled “Machines and microcosms. Leonardo on the human body.” Laurenza’s talk will look at the Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci (1492-1519) and his diverse areas of study encompassing biology, technology, and natural philosophy. Ultimately, da Vinci’s investigations helped contribute to a better understanding of chemistry, geometry, mathematics, mechanical engineering, optics, physics, civil engineering, and more.

In advance of the meeting, Sergio Cerutti, professor in Biomedical Engineering in the Department of Electronics, Information and Bioengineering at the Politecnico di Milano and Conference Chair of EMBC ’15, sat down with one of Laurenza’s colleagues, Pietro Cesare Marani, professor of Modern Art History and Museology at the Politecnico di Milano and curator of an exhibition on Leonardo da Vinci at the Royal Palace of Milan, to learn a little more about Leonardo’s place in history as the world’s first artist-engineer.

Cerutti: Would it be too much of a stretch to characterize Leonardo da Vinci as the “first” biomedical engineer? If so, why? If not, why not?

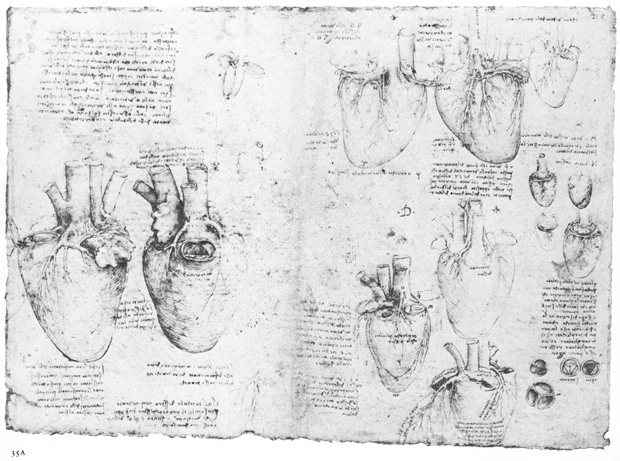

Marani: It’s difficult to apply modern scientific concepts to Leonardo. When asked if Leonardo was the first bioengineer of history, you can say yes, but you need to position his research and interests within the context of knowledge of his time. If we look, for example, at the studies that Leonardo has done in the field of anatomy, in optics, and especially in the study of fluids, we can confirm that. Leonardo analyzes the outside world first through a “visual analysis” of phenomena. But it leads him to exploring the possibility of intervening to change what he has observed or what he considers to be the “process” of the observed phenomena. We see that in the study of anatomy and the movement of fluids. The study of water, that he obviously uses as a paradigm for the study of the circulation of blood, leads him, for example, to introduce “markers” in the water, which may be grains of dust, sand, etc., which help him to understand the direction of water flow. That induces him to make helpful considerations to solve certain problems of blood circulation.

Early in his career, there are also close similarities between the study of the behavior of fluids and the study of the propagation of visual rays, which are always straight motions. Studying the scattering of light and the spread of what he calls the “spezie” (spices) in the air, mainly on the basis of Euclidean geometry, leads him to suggest the possibility of intervention on this propagation of rays and on flows of liquids. By introducing obstacles in fluids, such as small items that have a concave-convex shape, he realized that it was possible, for example, to produce changes of direction in a current of water in such a way as to transform the shape and the path of the river bed.

So, first his extraordinary ability of visual observation, then the introduction through experiments of some elements that change the motion of the water, the blood and fluids in general, gave him the possibility to intervene in order to obtain the determined results. In that way, maybe we can call him a “bioengineer” in the modern sense of the word. This is also evident in his diagrams of human anatomy in which he draws muscle bundles leading to the creation of “anatomical models” where he replaces nerves with what he calls “thread yarn,” i.e. strings that simulate the tendons or even nerves.

Cerutti: What separates Leonardo da Vinci so completely from what other scientists might have been doing in that time period? Were other artists working on the same issues?

Marani: Surely there have been artists and engineers who have anticipated some of Leonardo’s research, though not with the same depth and above all with the same capacity of graphic representation. What previous artists lacked was the ability to observe nature and to intervene in the processes of nature, as Leonardo does. His predecessors had fewer graphic tools available, had a lower capacity for observation. The analysis they did of phenomena was based primarily on the perpetuation of concepts transmitted by authorities, by official sources. The great Leonardo’s innovation was to have taken well-established concepts and subjected them to the direct verification of phenomena by always using his great observational capability, equipped with his extraordinary skill in transforming what he saw in a graphic schematization of processes.

Marani: Surely there have been artists and engineers who have anticipated some of Leonardo’s research, though not with the same depth and above all with the same capacity of graphic representation. What previous artists lacked was the ability to observe nature and to intervene in the processes of nature, as Leonardo does. His predecessors had fewer graphic tools available, had a lower capacity for observation. The analysis they did of phenomena was based primarily on the perpetuation of concepts transmitted by authorities, by official sources. The great Leonardo’s innovation was to have taken well-established concepts and subjected them to the direct verification of phenomena by always using his great observational capability, equipped with his extraordinary skill in transforming what he saw in a graphic schematization of processes.

Cerutti: If Leonardo da Vinci were alive today, what do you feel would be the problems he might be addressing? What medium would he use as an artist? What would be his utmost concern as a scientist?

Marani: It’s always difficult to answer such a question because it requires actualizing today’s problems that were posed to him, perhaps for the first time, five centuries ago. Today, definitely Leonardo would have used electronic technologies and computers. But to have caught a glimpse of the possibilities of studying that five centuries ago would be unthinkable. But if we think that twenty years ago, many of the tools we use today were unthinkable we understand that an important path of science and technology has been fulfilled and Leonardo would certain have been able to appreciate this evolution. I believe that today he would be especially involved in the study of cosmological problems. What he cared a lot about was understanding, on the basis of his knowledge of Euclidean geometry, the distance between the Sun and Earth and the Earth and Moon. He would surely have used the right tools to respond to these questions. One of his recurring concerns was about the moon, especially how it hangs in the cosmos. Therefore, an essential problem for him was that of gravity and the study of the relation of planets to one another. In this case, Leonardo would definitely have access to great tools to answer these kinds of questions.

Cerutti: Of the many sketches and drawings left by da Vinci, what do you believe to hold the most relevance for today’s biomedical engineers?

Marani: We can say that one of the topics in which Leonardo did not get great results is in the study of optics and vision problems, because even Leonardo, in this case, leaned on a knowledge transmitted from antiquity from Arab philosophers to more recent eras and the Renaissance. On the other hand, worth noting is the eye model which Leonardo intended to develop around 1508-1510, during his late studies of optics, as demonstrated by some drawings of the Manuscripts D of the Institut de France. In these, Leonardo conceives of a big spherical glass vessel full of water which and supposes to insert inside a man’s head, in order to verify the effects of water which acts as a lens refracting images. In fact, in his studies on the eye, Leonardo followed an abstract conception dating back to Alhazen (XI century AD), who had introduced a model of the eye composed of inner spherical components. Such an abstract model, which Leonardo has drawn several times in the Atlantic Codex and in his manuscripts, is the one which the artist-scientist wanted to verify through his glass model, by making use of an anatomical dissection of the eye immersed in albumen (it is not demonstrated he ever really did it).

But if, from an investigative point of view, he does not reach new conclusions, it’s always interesting to see how Leonardo is looking for tools to facilitate or improve his vision. One of his concerns is that visual faculties decrease with age. One of his most innovative proposals is the study of lenses and glasses to help overcome the aging process through what is now the very common invention of eyeglasses. This knowledge was probably acquired in the field of glassmaking among those who manufactured glass tiles for windows who probably noticed how a concave or convex glass enlarges images. This is something of great importance because glasses were opposed by the Church because they gave a distorted view of reality, and therefore did not correspond to the “truth.”

From the biomedical perspective, this is one of the many examples of how Leonardo went beyond the concerns or the limitations of his time, towards scientific research, having instead an objective to improve life and take care of sight defects due to aging through the use of such “diabolical” tools as glasses.

Cerutti: What is the one thing most people would be surprised to learn about Leonardo da Vinci?

Marani: There are so many things that are fascinating about the research of Leonardo. Examples are numerous, but one of the most curious is that of Leonardo’s continued interest in the reproduction of natural phenomena that had bearing on his artistic creation. It certainly would be interesting to know that the famous “sfumato” of Leonardo is nothing if not the result of a scientific air observation that enlarged upon what he calls “aria grossa” (big air), the tiny water particles or moisture interposed between the eye and the subject to be represented. Therefore the public will be pleased to know that the term “sfumato” perhaps derives from this cloud over the image due to moisture. This also explains the popularity of Leonardo’s paintings in the romantic age wrapped in this mysterious aura, by these mists. But all this has a scientific explanation that resides in the great ability of Leonardo in interpreting even the phenomenon of misty air full of moisture.

Cerutti: As a colleague at the Politecnico di Milano, you are certainly sensitive to identify, if it exists, a link between artistic vision and that of the science and technology of Leonardo da Vinci, as witnessed by his works. What do you think from your experienced position?

Marani: I think that this continuous transition between the artistic and scientific fields is very much grounded in Leonardo’s personality. This is not an evolution. For a long time critics thought that Leonardo started as a 15th century artist formed in the practical environment of a craft and training workshop and gradually moved toward becoming a scientist. This is not absolutely true: these two moments are always together present in Leonardo’s mind and personality.

For example, Leonardo took a reverse step from science and its applications to the artistic field. And this is proven by his studies, for example in the phenomena of friction (“confregazione”) between elements and materials that led him to observe how the rotating pins or gears that grind each other produce on the surface of bodies incised lines for winches, beams, and bolt mechanisms that move with each other, thus creating etchings. Then, this causes a continuous passage of artistic observation because we see that Leonardo replaces the technique of diagonal parallel hatching with curvilinear hatches of the convexity of the shapes that he saw as changes due to the rubbing. So it’s a kind of inverse way which is not in favor of either theory but that proves the simultaneous presence of these two moments: the scientific observation and the artistic achievement. The result of this observation was to give three-dimensionality, volume to his figures, his shapes, something that doesn’t happen except in fairly advanced age of his scientific and artistic activities.

Cerutti: Leonardo certainly embodies a truly “polytechnic” figure, i.e. a person who has managed to bring together the two cultures of art and of science and technology. Is this a good example for a modern biomedical engineer who is called to synthesize different cultures like Science with Medicine, Biology, etc.? What could Leonardo suggest in this regard?

Marani: He might suggest a possibility of continuous verification of two poles—scientific and artistic—interwoven and used at their best, which could be a special key to the advancement of knowledge. If we think of what Leonardo has anticipated and foreshadowed by his research, with the little means that was available at the time, and we also think of the large quantity of tools and possibilities that we have as historians and scientists today, we cannot help but make an example of his ability to interconnect the various fields of knowledge, increasing by ten-fold their cognitive potential when intertwined, thereby increasing our possibilities for knowledge. And this is a good example of “interdisciplinarity” (to use a modern expression) which constitutes a fundamental background for biomedical engineers today.

Cerutti: Thank you for your insight. We look forward to hearing more about da Vinci at Dr. Laurenza’s keynote address in August!