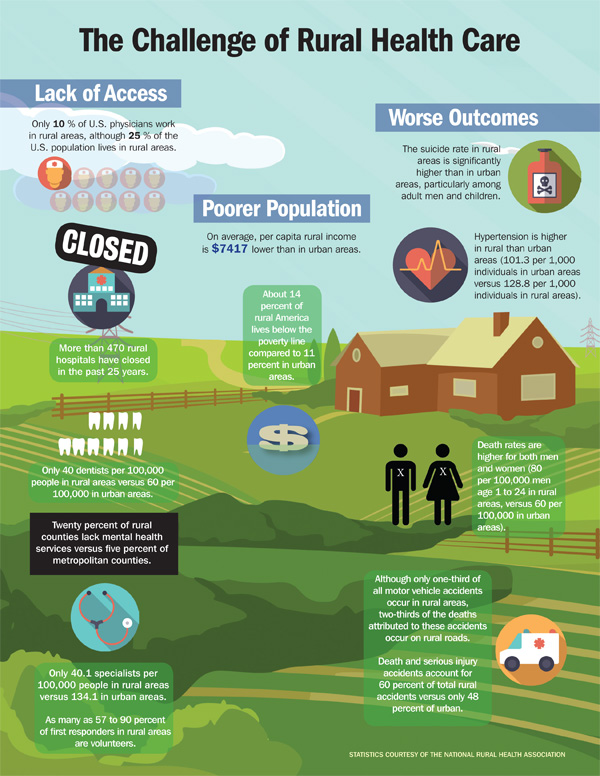

The United States is hailed as providing the most advanced health care the world has to offer. With cutting-edge medical devices, groundbreaking procedures, and innovative technologies, our hospitals and medical centers define what the global community sees as modern biomedicine. Engineers and clinicians continue to push and reshape this standard with new inventions enabled by a rapidly developing knowledge base. However, the fruit of this advancement has not benefited Americans equally. Millions still face significant obstacles to access health care, and our rural communities in particular have been left behind (see also “The Challenge of Rural Health Care”).

[accordion title=”The Challenge of Rural Health Care”]

[/accordion]

Rural populations, which tend to be older, poorer, and sicker than other groups, have an especially pronounced need for high-quality and timely care. In spite of this, rural areas across the country suffer from inadequate health care delivery. While almost a fifth of Americans live in rural areas, only a tenth of physicians do. In fact, over two-thirds of all Health Professional Shortage Areas, as designated by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), are in rural areas [1]. These shortages result in long travel distances to many medical services, long wait times for appointments, and limited access to certain specialists within a given geographic area. While the federal government has provided financial incentives to encourage physicians to set up their practices in these underserved areas, the problem persists.

As their patients struggle to access care, the health care providers who serve rural populations face their own set of related challenges. Due to shortages, they often have very large, often unmanageable patient panels. Moreover, they lack connections to specialists who are mostly concentrated in urban academic medical centers where nearby primary care physicians (PCPs) can much more easily consult specialist colleagues when diagnosing or treating a patient with a complex illness. This reduced access to specialists decreases the quality of care rural patients receive and depresses rural provider morale.

In addition to the social determinants of health, one key factor affecting rural health beyond health care access is technological connectivity. Rural areas are much more likely than urban areas to have limited broadband access and Internet adoption, a situation associated with worsened health outcomes in the form of higher rates of diabetes, obesity, and preventable hospitalizations [2].

Tackling the deficits in rural access to health care is a daunting task, but delivery system reforms hold significant potential to reduce them. Empowered by new communications technologies, broadband access, and novel payment models, these initiatives are well poised to revolutionize rural health care and improve the health outcomes of the 60 million Americans who live in rural areas.

Broadening access through telecommunication initiatives

Transforming the PCP–specialist relationship is a necessary step toward improving provider collaboration in caring for rural patients and increasing access to specialists. Provider education, facilitated by telecommunication, can allow PCPs in rural areas to learn from specialists about how to diagnose and treat common or relevant illnesses for which a PCP is not as well prepared. Many providers would seize the opportunity to leverage the expertise of urban academic medical centers to better care for their patients in rural communities.

While this type of education is largely preventive and focused on capacity building, electronic consultations would enable PCPs to confer with specialists in real time about a specific case. Ultimately, as we move toward a more connected world where physical distance ceases to be a barrier to communication, it should be just as easy for a rural provider to consult with a specialist as it is for an urban provider to do so.

Lastly, telemedicine provides an avenue for patients to directly interface with physicians in urban centers, increasing the specialist presence in rural health care. More health systems are likely to invest in offering these services to patients and their doctors as the infrastructure grows and evidence of their cost effectiveness continues to build.

A number of ambitious innovators have used these approaches to take on the challenges facing rural health care providers and patients. The initiative Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (Project ECHO) demonstrates how commonplace telecommunication services can bridge the gap between urban academic medical centers and rural areas. Affiliated with the University of New Mexico but having achieved a nationwide presence, Project ECHO employs a hub-and-spoke knowledge-sharing model to connect academic hubs with community providers. Its expert specialist teams use multipoint videoconferencing to conduct virtual clinics with rural physicians, teaching them how to provide specialty care to patients in their own communities.

The project began with a focus on hepatitis C and has since expanded to an array of medical conditions, ranging from diabetes to HIV. With 87 hubs worldwide covering more than 45 complex conditions, this model has grown rapidly over the last few years and has been recognized for its potential to significantly increase the quality of care in rural areas. Earlier in 2016, the DHHS announced the earmarking of US$9 million in grant money to extend opioid abuse training and improve addiction treatment in rural areas, using Project ECHO as the primary means.

The Antenatal and Neonatal Guidelines, Education, and Learning System (ANGELS) provides another good example of successful implementation. This Arkansas-based program uses provider education, as Project ECHO does, along with telemedicine to treat high-risk pregnancies and also cares for other high-intensity conditions, such as stroke and spinal cord injuries. Programs like these are not using particularly advanced technologies. Rather, they are building systems and networks, based on virtual appointments and telecommunication, that foster professional learning and collaboration while increasing accessibility for patients who need it.

Mississippi is pioneering a number of its own innovations in this space. Its efforts to combat diabetes demonstrate how valuable these types of initiatives can be. Of the state’s 13% of adults with diabetes, over half live in rural areas with limited health care access. In light of these challenges, Mississippi set up the Diabetes Telehealth Network, which uses remote care management to support rural patients. If results from the pilot scale up to a statewide level, the state stands to save over US$3,000 per patient, and its Medicaid program is projected to save a total of almost US$200 million each year.

In addition to connecting individuals, there is increasing recognition that we ought to use these technologies to connect systems throughout health care as well. For many patients in rural areas, their only point of access to the care system is a freestanding emergency department (ED). Programs like TelEmergency and TeleStroke at the University of Mississippi Medical Center have for years demonstrated how telemedicine can save lives by connecting rural EDs to urban centers and facilitating a seamless transfer of care between providers. The medical center has formed a connected network where its main hub emergency department is connected with over 28 different EDs across rural Mississippi, allowing for quick expert consults in time-sensitive situations.

The University of Massachusetts Medical Center has taken these emergency care delivery innovations a step further by employing Google Glass to allow physicians there to remotely experience the provision of care by a physician in the same room as the patient. This enhances the quality of the medical direction by giving expert clinicians a front-row seat to patient care even though they are thousands of miles away. Google Glass has also entered the operating room at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, as well as many other places, where it is being used to record surgeries as a way to help train providers in rural areas (both in the United States and abroad in India and other developing nations). It is not difficult to imagine that Google Glass and similar devices will soon serve an assistive function during medical procedures as well, guiding the surgeons as they cut, tie, and sew.

Technology Promises to Revolutionize Rural Health Care

Clearly, technological innovation has played a crucial role in improving rural health care through telemedicine, Google Glass, and other advancements. The Federal Communications Commission recently released its Mapping Broadband Health in America tool, which will allow researchers, policymakers, and providers to identify areas where limited broadband access is contributing to poor health. This initiative and others like it will help more rural communities benefit from technologies that are already being used to deliver care. Soon-to-come technologies will be just as transformative.

With the era of fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks on the horizon, new forms of delivering health care will emerge. The faster and more intelligent networks, back-end cloud-based computing services, and extremely low latency that 5G will bring to communities across the nation have the potential to revolutionize rural access. Experts predict that previously unimaginable innovations such as remote surgery will enter the realm of possibility once 5G becomes mainstream.

Experienced surgeons at urban medical centers will be able to direct a surgical team and even play a role in the actual performance of a procedure in rural clinics using virtual tools and advanced robotics. Health-related sensors will proliferate and become part of a new health Internet of Things, creating unprecedented amounts of data that can be harnessed for actionable insights to improve health, inform providers, and alert patients when their metrics indicate a need for medical attention. Imaging, diagnostics, and data analytics will become more accessible and valuable as information sharing increases the connectedness of health systems and as machine learning algorithms use big data to increase our predictive capabilities. While much of this innovation is likely to begin in urban areas, rural areas will be able to adopt successful programs piloted in nearby cities.

However, delivery system reforms of this scale do not occur in a silo. They interact at every stage with policy and payment structures, which are currently at odds with the innovation and progress that rural Americans need.

Policy Reforms are Needed

While efforts are underway to transform payment mechanisms in American health care, our current system is still predominantly based in fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement, which pays providers based on the quantity and type of services they provide. With little emphasis placed on the quality or efficiency of care, FFS systems do not incentivize investment in innovation, especially because there is considerable uncertainty about if and when new modes of delivering care will be reimbursed by Medicare and private insurers. For instance, Medicare reimburses for telemedicine in a very limited fashion, restricted to certain rural areas. As a result, many providers lack the incentives or the revenue streams to partake in and finance new initiatives like Project ECHO or ANGELS.

Change is coming, gradually. New policies under the Affordable Care Act and the Medicare and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) Reauthorization Act of 2015 are driving a shift toward paying for value in health care. The focus on alternative payment models that pay providers on a per member per month capitated basis aligns with delivery system reform. New models such as Accountable Care Organizations and bundled payments reward cost-effective practices that improve and preserve health. Care teams and hospitals will be rewarded for better care, especially for chronic diseases like diabetes, that keeps patients from needing to visit an ER. For rural patients, this means an uptick in targeted virtual services as well as improved data exchange and care coordination. While startup investment might be high for some initiatives, the payoff will be considerable for providers and patients. Increasing alignment of payment models with new delivery systems will encourage interprovider communication and drive widespread adoption of the pilot programs discussed previously.

Policies that target rural areas will also play a significant role in improving rural health. One path is government- and university-funded programs that provide loan forgiveness and tuition scholarships for medical students who commit to serving rural populations as PCPs or specialists. These efforts should be coupled with increased incentives and regulatory flexibility for investment in rural health care. Public–private partnerships between local government agencies and privately held health systems offer the potential to accelerate innovation in this financially and politically complex space.

Improving rural health demands system-level innovation and policy reform as well as buy-in and cooperation from a range of stakeholders, including providers, payers, and governments at a federal, state, and local levels. The challenges are steep, but we are already seeing signs of innovation and change. As providers, entrepreneurs, and policymakers prepare to seize opportunities to transform rural health care, they ought to remember who should be at the center of their efforts: patients.

References

- These data were taken from the United States Census Bureau and the National Rural Health Association. They are summarized in the Health Affairs Blog, Reference.

- Based on data from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s County Health Rankings and the Federal Communications Commission. Analysis performed by David Pittman and reported in Politico Morning eHealth on August 3, 2016.

For More Information

- K. Patel, M. B. McClellan, K. Samuels, and M. Darling. (2014, Dec. 17). Opportunities to transform rural health care. Health360, The Brookings Institution. [Online].

- K. Patel, M. Darling, K. Samuels, and M. B. McClellan. (2014, Dec. 5). Transforming rural health care: high-quality, sustainable access to specialty care. Health Affairs Blog. [Online].

- D. M. West. (2016, July 14). How 5G technology enables the health internet of things. The Brookings Institution. [Online].