It could be as simple as a hospital worker downloading an app on a personal cell phone during a lunch break. That phone—or the hundreds of other unsecured devices in a hospital—can be an entry point for hackers to wriggle their way into the hospital’s network, enabling them to encrypt data like patient records. This encryption holds the entire infrastructure of the hospital hostage. Only the hackers hold the decryption key and will share it—for a price.

Ransomware and other cyber attacks on health centers have been in headlines lately due to the potentially devastating impact they can have on services and the seemingly rapid frequency in attacks. Between February and May 2016 alone, cyber attacks affected Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center (February), Washington-area MedStar Health, which operates nearly a dozen hospitals in the DC area (March), Kentucky-based Methodist Hospital (March), Ottawa Hospital (March), Prime Healthcare Services Inc.’s Chino Valley Medical Center and Desert Valley Hospital of Victorville (March), and many others.

Ransomware is just the latest in cyberattacks on healthcare systems. Hospitals and medical facilities face additional threats that all industries have to contend with: phishing, malware, theft of personal data records and other malfunctions of equipment or networks. As with any industry, better training of the IT team and proper antiviral installation can go a long way toward ensuring cyber safety. However, healthcare settings have seen more attacks than other industries in recent times, so much so that the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate just awarded a consortium US$1.8 million to develop technology to defend medical devices from cyber attacks.

[accordion title=”Expert Advice on Keeping Hospitals Cyber Secure”]

From ransomware attacks to electronic medical record and identity theft, hospitals are particularly vulnerable to cyber breaches. Aside from using antivirus programs and keeping software up-to-date, experts in the field recommend several strategies to healthcare providers to keep themselves—and their patients—safe.

Those familiar with healthcare attacks particularly emphasize the need for institutes to make the financial commitment to develop strong IT infrastructures and hire personnel to deter cyber crimes. Healthcare professionals must first acknowledge just how damaging cyberattacks can be and then dedicate resources to the problem. Hackers never rest: attacks are constantly evolving in sophistication, so a one-time commitment to digital defense is not enough. Rather, security measures must continually be assessed and updated.

James Scott, co-founder, Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology

- The only solution to ransomware is to regularly backup data on an external system, to practice basic cyber-hygiene, and to use layered defenses.

- Hospitals need to recognize the threats posed to them and take measures to protect their systems according to the value of the data stored, transferred, or processed within. They must remain vigilant against cyber threats instead of being a sedentary target.

- Train staff to only open emails from known contacts and to never click on links in any emails.

Avi Rubin, Professor, Johns Hopkins University

- Hire a great chief information security officer and give him or her the proper resources to build an elite team.

- Increase the resources available for security in the healthcare space. There are known techniques for better computer and network hygiene, but they require spending money on good administrators and the right protection system.

Kevin Fu, Associate Professor, University of Michigan & Chief Scientist, Virta Labs

- The basic hygiene boils down to: enumerating medical device assets at risk; deploying compensating security controls that mitigate those specific risks; and continuously measuring the effectiveness of those controls since threats can change quickly.

- Because of human nature, people tend to jump to deploying security solutions before properly enumerating risks then forget to monitor the effectiveness of controls. Never fall in love with a security control.

Ashley Thomas, Healthcare Attorney, Hall, Render, Killian, Heath & Lyman

- Back up, back up, back up! Regularly back up data to ensure that data can be restored in the event of an attack and keep any recent backup off-site.

- Hospitals should work with trained experts and outside legal counsel to help develop and implement cyber security policies and procedures that can be tailored to the provider.

- Having cyber liability insurance can help mitigate financial risk of exposure through cyber attacks and data breaches.

Axel Wirth, Distinguished Technical Architect, Symantec

- It’s not enough to put antivirus programs in your workplace. You need to defend at all levels, from your network perimeters and files down to individual devices.

- Be aware that medical devices have been exploited because they are the weak entry point into a network and can be used for an attack on other systems.

David Kotz, Professor of Computer Science, Dartmouth College

- Build cyber security requirements into your technology acquisition process, whether for information systems, cloud providers or medical devices. Ensure that each new technology acquisition and installation has been reviewed for cyber security risks and configured properly, before connection to your network.

- Consider means for deauthentication, that is, ensuring that systems lock-screen or log-out when someone other than the authenticated person steps in to use a terminal.

- Find meaningful ways to integrate mobile devices into your workflow without opening new security risks and recognize that staff will likely use those devices even if you do not support them. It’s better to get ahead of the curve and support those devices securely.

Read more on cyber security guidance at The National Institute of Standards and Technology, www.nist.gov.

[/accordion]

“I think the greatest threats to hospitals and patients right now are the prevalence of malware and the ease with which attackers are able to get that malware into hospital networks. Once the attackers can run their arbitrary code on the medical devices and hospital IT networks, they can launch ransomware attacks, denial of service attacks, and exposure of sensitive information,” says Rubin.

Holes in the Machine

Why are hospitals so susceptible to cyberattack? One major reason: the industry’s lack of spending on security—in part because of the focus on HIPAA compliance and patient privacy—has caused cyber defenses to lag. Additionally, the healthcare setting has distinct features that make it more challenging to secure a system than, say a banking or communications setting. In particular, healthcare often needs to err on the side of being “open” to ensure that barriers to data and information are low, as patient safety is on the line.

“Healthcare has traditionally been reluctant to add too many security controls into their systems because of the concern that they may cause problems on their own,” says Axel Wirth, distinguished technical architect of the security software company Symantec. “Healthcare is traditionally an open industry where easy and fast access to information can be a matter of life or death.”

One example of a security measure interfering with patient delivery is the Merge Hemo programmable diagnostic computer, used for cardiac procedures. According to the FDA’s adverse event report, in the middle of a heart catheterization procedure, the device went blank for about 5 minutes and had to be rebooted. It turns out that anti-malware software was performing its hourly scan. While the procedure was successful, the FDA report acknowledges that there “was a potential for a delay in care that results in harm to the patient.” The device was misconfigured and should have never scanned during the procedure, according to the manufacturer. However, the incident illustrates why healthcare professionals have been reluctant to add more security features.

“As with any highly complex system, the more components the more likely it is that something goes wrong, be it due to a technical failure or users being overwhelmed with complexity,” says Wirth. “Implementing security controls has to be done very carefully not to risk impeding on care delivery.” For example, when a user enters an incorrect password or pin number several times and gets locked out of a system, this is typically a minor inconvenience for most professionals or consumers. But if this were to happen to a doctor during an emergency procedure it could have a grave impact on patient wellness.

“Devices and records have to be accessible to many providers—they have to not hinder care in the event of a failure,” adds Christoph Lehmann, a medical doctor and professor of biomedical informatics and pediatrics at Vanderbilt University. “The fact that so much valuable information is stored in one place makes healthcare settings an attractive target. Also the large number of workstations and the relative little training for many employees increases the risk.”

The Year of the Ransom

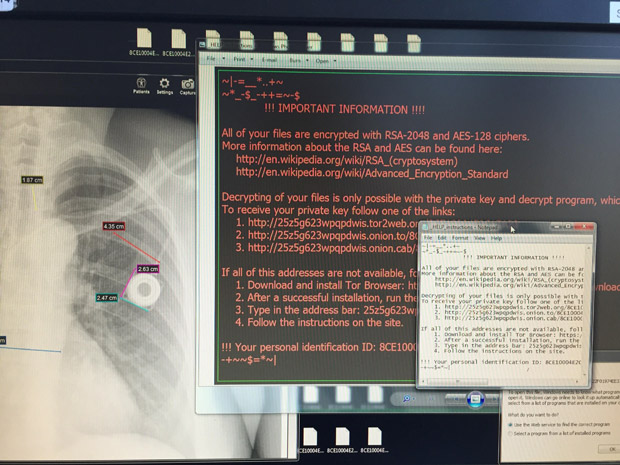

In February 2016, hackers infiltrated and locked down the computer system of Hollywood Presbyterian Medical Center in Los Angeles using Locky ransomware. Despite enlisting help from the FBI, the hospital allegedly had to rely on paper medical records and turn away new patients due to the turmoil. Ransomware, such as Locky, CryptoWall and CryptoLocker, is a malware program which, once it gets into a system through an insecure link or malware attack, can restrict and encrypt data, effectively holding the information ransom until an amount is paid (often through bitcoin, a digital currency that is hard to trace).

The malware was said to affect some of the center’s systems used in the emergency room and to operate testing machines such as CT or MRI machines. After almost two weeks of crippled operations, Hollywood Presbyterian paid a US$17,000 ransom because lives were at stake and law enforcement did not have a better solution, according to James Scott, co-founder and senior fellow of the Institute for Critical Infrastructure Technology (ICIT).

“However, by paying the ransom, the hospital inadvertently signaled to threat actors that healthcare organizations were easy and profitable targets. After Hollywood Presbyterian, ransomware attacks became more prevalent,” says Scott. “All of these attacks are part of a deeper systematic problem: hospitals lack the cyber-hygiene and layered defenses necessary to mitigate the risks posed to them.”

Indeed, Symantec has data confirming the number of breaches and incidents in healthcare are higher than in other industries. “For example, most recently we have seen an uptick in ransomware attacks,” says Wirth. “It’s like the bad guys realized that there’s a lot of money to be made because when hospital computer systems are shut down their reputation and revenue suffer and it potentially becomes a health crisis, so they will likely pay.” The hackers, he adds, tend to operate in well-organized groups and can originate from anywhere around the globe and attack any healthcare facility, no matter how small or remote. This is especially concerning in light of the flourishing underground market for hacking services, malware, tools and data.

The FBI put out an alert on ransomware in February advising companies not to pay the ransom because it can encourage more criminal activity. “But this puts healthcare providers in a difficult position because a lot of them have not prepared for these attacks by implementing appropriate backup and malware systems,” says healthcare attorney Ashley Thomas of the law firm Hall, Render, Killian, Heath & Lyman.

The FBI’s Internet Crime Complaint Center has reported that ransomware, Cryptowall, has been a source of 992 complaints from April 2014 to June 2015 with total losses at more than US$18 million. But, says Thomas, ransomware attacks are likely happening far more than is reported since there isn’t a federal law requiring hospitals to report ransomware attacks or even notify patients. “There is debate in the healthcare legal community now on whether ransomware should be considered a data breach for purposes of notification under HIPAA,” says Thomas.

Hospitals are the new target for these kinds of attacks, but anyone who has a digital system—such as parents with pictures on their computer or teenagers with saved video games—could be viable targets.

Assassination Through Pacemaker

In a 2013 interview on CBS’s 60 Minutes, former US Vice-President Dick Cheney reported that doctors disabled his pacemaker’s wireless connection to prevent personal lethal attacks. Such cyber assassination attempts have never been reported, though they have been depicted in fiction and remain a potential, though unlikely, threat, according to experts. In tests, researchers were able to exploit security weakness in devices to, for example, change the amount of insulin released from a pump or change the output of a pacemaker, bypassing security features and alerts.

But, says Kevin Fu, associate professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Michigan and chief scientist at Virta Labs, the threat of such personalized medical attacks have been blown out of proportion by the media. “Patients shouldn’t be running for the hills—they are still far better off with these devices than without,” he says. “While pacemaker security has room for improvement, the bigger risk is wide-scale unavailability of patient care because of poor cybersecurity hygiene during manufacturing and delivery of care. We click on links. We share USB drives. We install ransomware. Malice is not a prerequisite to harm. It’s basic hygiene.”

Fu, who runs the Archimedes Center for Medical Device Security, focuses on improving the manufacturing of medical devices to prevent these kinds of individual attacks as well as vulnerabilities that medical devices can introduce into larger hospital systems. The team surveys a vast array of devices, including pacemakers, percolators, infusion pumps, and radiological and imaging systems. “We want to have security built in rather than bolted on,” says Fu. “The good news is most of the device companies are beefing up cyber security programs.” It took 165 years for the medical community to appreciate the importance of hand washing, Fu points out, so it will take some time for the industry to get onboard with cyber “hygiene” as well.

Rather than being used to alter or attack the health of individuals, medical devices are much more likely to be used as the point of entry into a networked system where hackers can install malware. The abundance of networked or wireless devices add insecure components to a networked system that can be the weak points of entry into a system. These devices include diagnostic equipment (such as MRI machines or CT scanners), X-rays, infusion pumps, surgical devices, ventilators, dialysis machines and more.

In a 2015 report, the cyber security defense company TrapX found that a malware program called MEDJACK (for “medical device hijack”) infected hospitals by infiltrating medical devices. In one example, a hospital had robust antiviral software overall but attackers infected blood gas analyzers and extracted confidential data from the larger computer system. This one example illustrates how hospitals may be crawling with more cybernetic bugs than administrators realize.

“What’s really missing for hospitals is security tools that fit the clinical workflow,” says Fu. “There are a lot of really great tools out there but they do not sit well in a clinical environment. They tend to cause medical devices to flop over, lock up or reboot. But if you can’t measure your risks and assets it’s hard to protect a system.”

Software called vulnerability scanners look for weaknesses in enterprise programs, but when hospitals run these they often find out they have hundreds of security problems and no solutions to fix them. To combat this, Fu’s company Virtua Labs developed a piece of software currently in beta testing called Blue Flow, which helps hospitals measure their security risks and discover which devices are susceptible to virtual threats.

Going Once, Going Twice: The High Worth of a Medical Record

In 2015, several high-profile cyberattacks compromised millions of patient records from UCLA Health System and, earlier in the year, health insurance company Anthem. Patient health records, it turns out, are valuable commodities on the black market.

“We know from various data sources that the value of healthcare data—which can include names, addresses, physical descriptions and next of kin—is multiple times higher in the underground economy as compared to credit card info because it’s more complete,” says Wirth. “You can cancel a credit card if it’s stolen but you can’t cancel your medical record.”

And it’s not just large hospitals that are at risk. Data can be stolen from smaller practitioners and even people’s homes. David Kotz, Champion International Professor in the Department of Computer Science at Dartmouth College, is working on a device to help smaller medical practices and patients protect their networks.

“My focus is on making wearable devices more secure and helping people understand how their data is collected, stored, and accessed,” says Kotz. “There’s a lot of work to be done to make vendors of devices think about cyber security and ensure their devices are safe. We also need to make it easier for people to manage devices and do it correctly.”

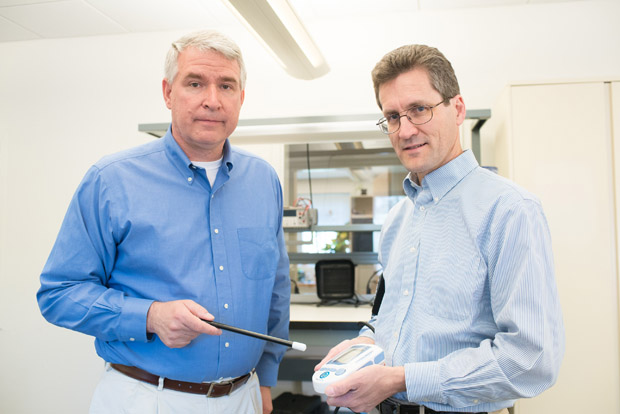

Kotz developed a wand-shaped security device called Wanda to help with easily improving security. Funded by the NSF and part of the Trustworthy Health and Wellness (ThaW) consortium, Wanda securely connects nearby devices to a Wi-fi network.

Users can point the wand within 6-8 inches of a device that’s Wi-fi-enabled and the wand transfers network settings—including complex passwords that will hinder cyberattacks—to a new device. It can also connect two devices, such as a smart treadmill to a Bluetooth television. “The problem today is that people choose guessable or no passwords or leave their networks wide open,” says Kotz. Part of the lack of security is that many users don’t want to take the time and effort to properly configure new devices or—particularly in the cases of limited interfaces—simply don’t know how. “With Wanda, we can let users express intentionality by pointing, which is something everyone understands intuitively.”

Kotz says devices like Wanda can help smaller organizations that need to manage increasing numbers of networked devices, as small clinics with a doctor or a few nurses typically don’t have full-time tech support to configure and manage the many devices. His team is improving the device and has a patent pending.

Other future problems with cyberattacks include the increased use of telemedicine and even telesurgery, both of which have the potential to transform healthcare in remote or underserved areas. However, with the advent of more network-based medical solutions, there are likely to be hackers at the ready to exploit such systems if they are not properly protected. As devices and healthcare technologies continue to advance and become more common, hospitals, medical practitioners, patients, and device manufacturers must together prioritize cyber safety to protect data, resources, and lives.