Immersive technologies may offer improved efficiency and precision for assessing, treating, and studying psychiatric and psychological conditions

While virtual reality (VR) is usually associated with video games or the simulated scenarios used to train airplane pilots and soldiers, new advances have brought VR technology into a whole different realm—that of mental health. After nearly three decades of study, VR has shown its utility for enhancing treatment for a range of conditions, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorder, and various phobias, such as fear of flying. Enthusiastic mental health professionals now believe VR may hold promise in treating and diagnosing many more mental health issues, including depression and autism spectrum disorders.

Expanded treatment for trauma

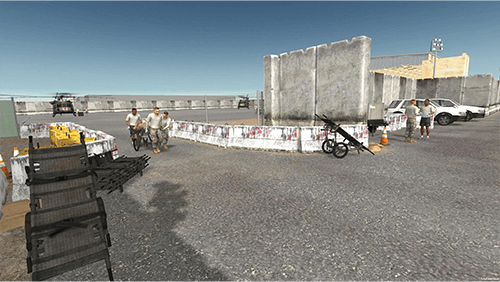

Bravemind, the first and leading VR tool for treating PTSD, was developed in 2004 by clinical psychologist Albert “Skip” Rizzo, Ph.D., the director of medical virtual reality at the University of Southern California’s Institute for Creative Technologies. An adaptation of traditional exposure therapy for PTSD, where patients typically confront a distressing memory or situation by imagining it, Bravemind has the power to immerse combat veterans in scenarios that resemble the context where their trauma occurred. A patient puts on a VR headset and is transported to a crowded marketplace in Iraq or a remote village in Afghanistan (Figure 1). “This is not some magical process,” Rizzo said. “We are following in lockstep the same protocol that’s used in imagination-only exposure therapy.”

Figure 1. Bravemind immerses participants, including combat veterans with PTSD, in scenarios that resemble the context where their trauma occurred. (Image courtesy of Skip Rizzo, Institute for Creative Technologies, University of Southern California.)

VR does offer significant advantages over imagination-based therapy: It is highly customizable to address specific features of a patient’s trauma history, highly immersive (and therefore more emotionally evocative), and easier for a clinician to monitor and control than imaginal exposure therapy. It may also be a more appealing therapeutic approach that can lower the barrier of entry for new patients—in a recent study that Rizzo coauthored, 77% of participants said they would prefer to receive treatment in VR [1].

Rizzo is now expanding Bravemind’s applications beyond military veterans who have seen combat. He is working with Barbara Rothbaum, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and director of the Trauma and Anxiety Recovery Program at the Emory University School of Medicine, who began studying PTSD in 1986 and has pioneered the use of VR exposure therapy to treat PTSD in combat veterans. Rizzo and Rothbaum have built new virtual environments—including military offices, apartments, bars, alleys, and cars—to help survivors of military sexual trauma learn to practice safely reentering the setting where an assault occurred in a therapeutic manner. In a feasibility trial, the intervention triggered no adverse events and led to a statistically significant reduction of PTSD symptoms [2].

In most cases, VR-assisted treatment only needs to be as good as traditional methods to prove its utility. But for patients with both PTSD and depression, a randomized controlled trial of 192 patients showed that Bravemind led to an even greater reduction in PTSD symptoms than did traditional exposure therapy [1]. Participants, including active-duty military service members and veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, were treated at a civilian medical center in New York, a Veterans Administration System, Long Beach, CA, USA, or Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD, USA. “When you ask people who are depressed to imagine and talk about their trauma, they often have difficulty activating the emotions needed to support this therapeutic process,” Rizzo said. “VR allows us to activate those emotions in ways that promote their reprocessing, [which can ultimately] reduce trauma-related fear and anxiety.”

Exposure therapy is not the only way VR can help patients with a trauma history. Clinical psychologist Jessica Stone, Ph.D., and developer Christopher Ewing created the Virtual Sandtray®© tool to treat people who have faced adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)—various forms of abuse, neglect, and household challenges that predict poor physical and mental health later in life.

The Virtual Sandtray was designed to expand upon the traditional physical sand tray, used in child-centered play therapy and other sand therapies. In play therapy, a therapist provides children and adolescents with a tray, filled with sand and miniature items (such as houses, trees, parents, siblings, or pets). Clients are encouraged to use the miniatures to tell their story to a therapist in a representative way.

Whereas a physical tray may hold 20–30 items, the Virtual Sandtray contains thousands. Clients can build and customize their world, including changing the weather and adding animation, allowing for a more immersive and customizable experience [3]. “We are actively adding new 3D models,” Stone said. “We currently have over 7,000 available for the user to customize their world, so they can achieve a level of immersion and embodiment, which is important—even necessary—to use this technology for mental health.”

Clinicians can observe patients from outside the virtual world or even join them as a witness in the virtual space. Rizzo and Stone are now working to deliver the platform to mental health providers around the world to help people experiencing distress from the Ukraine war, natural disasters, and other incidents.

Enhancer, not a replacement

Researchers are increasingly expanding the horizons of VR beyond its proven utility for helping patients confront traumatic memories and phobias.

Behavioral activation is a simple yet effective therapeutic approach for treating depression. It challenges patients to engage in pleasant and masterful activities each day to help break behavioral patterns of withdrawal and avoidance of daily life. In a small, randomized pilot study, Kim Bullock, MD, who directs Stanford University’s Virtual Reality & Immersive Technologies Program and Lab, compared the effect of adding pleasant activities in real life versus using simulated activities in VR. VR patients, who engaged in pleasant activities of their choice, such as swimming with virtual dolphins or virtually visiting the Maldives, had a clinically significant reduction in depressive symptoms following the trial [4]. These results suggest that VR activities could be used to treat depression in patients unable or unwilling to engage in real-life activities.

“What’s important is that VR is not replacing therapy,” Bullock said. “It’s a tool that enhances existing evidence-based therapies by making them more efficient, feasible, and comfortable.” For example, a patient who fears driving can practice driving in VR before getting in a car. Working with patients in a simulated vehicle, rather than a real one, is easier and less time-consuming for therapists, too. For that reason, VR tools may help reduce clinician burnout, giving therapists more bandwidth to complete other tasks while patients undergo guided virtual treatment, Bullock said.

Using VR for assessment

In addition to its value for treating mental health conditions, VR technology can be a powerful assessment tool. Collecting physiological data while patients are immersed in VR can give clinicians data to help with a diagnosis and allow researchers to test how well interventions are working.

Rothbaum runs the Emory Healthcare Veterans Program, a two-week intensive outpatient program for veterans with PTSD and other conditions, which is supported by the Wounded Warrior Project. Along with Rizzo, she and her team developed three standard VR clips that are used as an “activation paradigm” to test patients’ responses to stressors. Patients experience each 2-minute clip in VR: They join a convoy on a desert highway, drive a Humvee alone on the same highway, and patrol a Middle Eastern city on foot (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Bravemind may have particular utility for patients with both PTSD and depression, according to new research of active-duty military service members and veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. (Image courtesy of Skip Rizzo, Institute for Creative Technologies, University of Southern California.)

As they do so, Rothbaum’s team collects data on their physiological state, measuring the startle response with electromyography (which detects a sudden eye blink), as well as skin conductance, heartrate, and salivary cortisol. Through those tests, conducted before and after the two-week program, Rothbaum can assess whether patients are improving at the physiological level. “This gives us a more objective way to measure the effectiveness of treatment, because it doesn’t rely on self-reports,” she said.

To expand the diagnostic tools available to clinicians, Rizzo assembled a team that developed the Virtual Classroom, which can help identify and assess children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorders, and learning disabilities. When a child puts on the headset, they enter a virtual classroom where a teacher instructs them to complete a visual task (on the blackboard) or an audio task (answering a question out loud). Meanwhile, distractions typical to the classroom environment—a school bus driving past a window, a classmate whispering—occur in the background. The headset provides head movement data, indicating when a child becomes distracted [5]. The team is also testing the addition of eye-tracking data as they apply for FDA approval of the platform for assessing attentional problems in ADHD.

“We conduct research hand-in-hand with commercial development,” Rizzo said. “That allows us to secure the funding that makes these technologies future-proof—like updating the software when new devices come out—and to build a robust scientific evidence base along the way.”

Immersive technologies also play a role in affective computing, which uses machine learning and biological sensors to detect, interpret, and ultimately respond to human emotions. Devices that analyze tone of voice, facial expressions, eye gaze, subtle movements, and other data can provide rich data on an individual’s emotional state.

The Stanford Center for Precision Mental Health and Wellness (PMHW) has studied how components of affective computing can be combined with VR to customize treatment plans for patients with depression. By collecting detailed information about a patient’s emotional state during a VR activation paradigm (along with neuroimaging, genetic sequencing, and other data), clinicians can make personalized recommendations for treatment. For example, a person with depression may be provided with cognitive behavioral therapy, pharmaceuticals, transcranial magnetic stimulation, or a combination of the three, depending on the results of their assessment.

“It’s one thing to do a measurement, but in mental health, we have to do a measurement in response to a stimulus—and we need standard stimuli to be able to make any comparisons,” said Walter Greenleaf, Ph.D., a neuroscientist and expert in digital medicine at Stanford University’s Virtual Human Interaction Laboratory. That includes culturally- and age-appropriate standardized environments that reliably evoke feelings such as sadness, joy, and disgust. “VR really is the most effective way to do that,” he said.

Making research more rigorous

Beyond its direct uses for assessing and treating mental health disorders, VR is helping researchers who study addiction, depression, trauma, and other conditions to study interventions with increased methodological rigor. For example, Rothbaum designed a “virtual crack house” that simulates triggers—such as witnessing a drug deal—for people with substance use disorders. It has been shown to reliably increase cravings. “If we just ask someone to imagine their craving when a friend puts a line of cocaine in front them, we won’t know if we’ve evoked a response in a standardized way,” Greenleaf said.

Ultimately, researchers and clinicians alike report that the potential benefits of VR help legitimize the time and money required to pursue it. Rothbaum offers one suggestion for the field: think bigger.

“With VR, it’s really only limited by a person’s imagination and their budget,” she said. “We often think in terms of our current reality—creating a virtual version of it—but we’re really not limited to that.”

References

- J. Difede et al., “Enhancing exposure therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): A randomized clinical trial of virtual reality and imaginal exposure with a cognitive enhancer,” Transl. Psychiatry, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 1–9, Jul. 2022, doi: 10.1038/s41398-022-02066-x.

- L. Loucks et al., “You can do that? Feasibility of virtual reality exposure therapy in the treatment of PTSD due to military sexual trauma,” J. Anxiety Disorders, vol. 61, pp. 55–63, Jan. 2019, doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.06.004.

- H. Kaduson, “Using the Virtual Sandtray app: A boy’s journey to healing,” in Play Therapy and Telemental Health: Foundations, Populations, and Interventions, J. Stone, Ed. Evanston, IL, USA: Routledge, 2022, pp. 173–186.

- M. Paul, K. Bullock, and J. Bailenson, “Virtual reality behavioral activation for adults with major depressive disorder: Feasibility randomized controlled trial,” JMIR Mental Health, vol. 9, no. 5, May 2022, Art. no. e35526, doi: 10.2196/35526.

- S.-C. Yeh et al., “A virtual-reality system integrated with neuro-behavior sensing for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder intelligent assessment,” IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng., vol. 28, no. 9, pp. 1899–1907, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2020.3004545.